Yarbrough v. Commonwealth, 258 Va. 347, 519

S.E.2d 602 (Va. 1999) (Direct Appeal - Reversed).

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court,

Mecklenburg County, Charles L. McCormick, III, J., of capital murder and

robbery, and was sentenced to death. On appeal as of right from capital

murder conviction, and on transfer from the Court of Appeals of appeal

from robbery conviction, the Supreme Court, Koontz, J., held that: (1)

as matter of first impression, circuit court had discretion to appoint

as special assistant prosecutor an assistant Commonwealth's attorney

from another jurisdiction; (2) capital murder conviction was supported

by sufficient evidence; (3) finding of aggravating factor of vileness

was supported by sufficient evidence; (4) as matter of first impression,

defendant was entitled to have jury instructed regarding his parole-ineligible

status; and (5) circuit court's error in not instructing jury on capital

murder defendant's parole-ineligible status was not harmless. Affirmed

in part, sentence vacated, and case remanded. Compton, J., filed

dissenting opinion in which Carrico, C.J., joined.

KOONTZ, Justice.

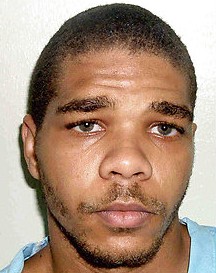

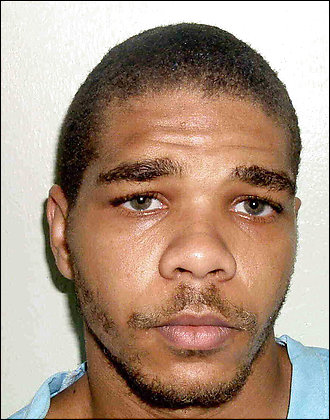

In this appeal, as required by Code § 17.1-313(A), we review the capital

murder conviction and death sentence imposed upon Robert Stacy

Yarbrough.FN1

FN1. Record number 990262 is the appeal of

Yarbrough's related conviction for robbery which was transferred to this

Court from the Court of Appeals. Although Yarbrough seeks to have this

conviction overturned, none of his assignments of error presents a

direct challenge to the merits of that conviction. Accordingly, his

conviction and sentence of life imprisonment on that charge will be

affirmed.

I. BACKGROUND

Under familiar principles of appellate review, we

will review the evidence in the light most favorable to the Commonwealth,

the party prevailing below. Clagett v. Commonwealth, 252 Va. 79, 84, 472

S.E.2d 263, 265 (1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 1122, 117 S.Ct. 972, 136

L.Ed.2d 856 (1997).

Yarbrough and Dominic Jackson Rainey had attended

high school together in Mecklenburg County prior to Rainey's moving to

Richmond with his mother. While on a subsequent visit to see his

grandfather in Mecklenburg County, Rainey renewed his acquaintance with

Yarbrough. On May 7, 1997, Yarbrough told Rainey of his plan to rob

Cyril Hugh Hamby, the 77-year-old owner of Hamby's Store on U.S. Route 1

in Mecklenburg County. The following evening, Yarbrough went to Rainey's

grandfather's house and told Rainey that “he was ready to go rob Mr.

Hamby.”

Yarbrough and Rainey were seen walking along U.S.

Route 1 toward Hamby's Store between 9:30 and 10:30 p.m. on May 8, 1997.

Yarbrough was armed with a shotgun. The two men waited at a picnic table

across the road until there were no customers in the store. Yarbrough

hid the shotgun under his coat and the two men entered the store. At

Yarbrough's direction, Rainey locked the front door.

Yarbrough pointed the shotgun at Hamby and ordered

him to come out from behind the store's counter. Yarbrough and Rainey

took Hamby to the living quarters at the rear of the store where they

found an electrical extension cord and string. Yarbrough brought Hamby

back into the public area of the store, forced him to lie on the floor

in an aisle, and tied Hamby's hands behind his back with the extension

cord and string.

Yarbrough went to the store's electrical circuit box

and turned off the outside lights. He then demanded that Hamby reveal

where guns were hidden in the store. When Hamby denied having any guns,

Yarbrough kicked Hamby in the head and upper left arm. Yarbrough then

forced the store's cash register open by dropping it on the floor and

took the money that was in the register.

Yarbrough returned to where Hamby was lying and,

pointing the shotgun at him, again demanded to be told where guns were

hidden in the store. When Hamby again denied having any guns, Yarbrough

put down the shotgun, took a knife from his pocket, and began to cut

Hamby's neck with a “sawing motion” as Hamby pleaded with Yarbrough to

stop.

After cutting Hamby's neck at least ten times,

Yarbrough rifled through Hamby's clothing and took his wallet. Yarbrough

and Rainey took beer, wine, and cigarettes from the store and left by

the back door. Yarbrough gave Rainey one hundred dollars in small bills

and kept a larger sum for himself.

Yarbrough and Rainey returned to Rainey's

grandfather's house to change clothes and then went to the home of

Conrad Dortch to buy marijuana. Dortch was not at home, so Yarbrough and

Rainey waited on the porch and drank the wine taken during the robbery.

Dortch arrived home at approximately 12:45 a.m. and sold Yarbrough a

marijuana cigarette for $10. According to Rainey, Yarbrough was

“flashing” his money. When Yarbrough and Rainey left Dortch's home,

Rainey threw an empty wine bottle into the yard.

Yarbrough and Rainey returned to Rainey's

grandfather's house where they spent the remainder of the night. Before

leaving in the morning, Yarbrough threw his tennis shoes, which were

stained with Hamby's blood, into a trash barrel behind the house.

Hamby's body was discovered at approximately 8:20

a.m. on May 9, 1997 by Betsy Russell, a former employee of Hamby's who

had been informed by a neighbor that “there was something wrong at the

store.” A subsequent autopsy revealed that Hamby had bled to death as a

result of deep, penetrating wounds to his neck.

According to a state medical examiner, Hamby's wounds

were “entirely consistent” with an attempted beheading, however, because

no major arteries were cut, it would have taken at least several minutes

for Hamby to have bled to death. Hamby also had several blunt force

injuries to his head and upper left arm consistent with his having been

kicked with moderate force.

On May 10, 1997, Dortch contacted the Virginia State

Police and told them of his encounter with Yarbrough and Rainey. Police

later recovered a wine bottle and label from Dortch's yard. The wine

bottle was of a brand that was sold at Hamby's store.

On May 14, 1997, police executed a search warrant at

Yarbrough's home and recovered bloodstained clothing and a three-bladed

“Uncle Henry” pocketknife. Police also recovered Yarbrough's tennis

shoes from the trash barrel behind Rainey's grandfather's house. DNA

testing of the bloodstains found on Yarbrough's shoes and clothing

established a positive match with Hamby's blood. DNA tests of blood

traces found on the “Uncle Henry” knife established that a mixture of

Hamby's and Yarbrough's DNA was present on the blade of the knife.

Forensic analysis of the bloodstain patterns on

Yarbrough's clothing supported the conclusion that they were consistent

with a spray of blood resulting from trauma. An expert testified that

the bloodstains on the lower front of Yarbrough's shirt were made “in

close proximity to the trauma that released the blood.”

Several shoeprints found in the store were identified

as having been made by Yarbrough's shoes, including those near the

circuit box, behind the counter, and in the bloodstains near Hamby's

head. Police also recovered Rainey's boots and identified prints found

near Hamby's feet and in the living quarters as having been made by

these boots.

* * *

D. “Life Means Life” Instruction

In assignments of error 2 and 3, Yarbrough contends

that the trial court erred in failing to instruct the jury that he would

be ineligible for parole if given a sentence of life imprisonment and

that the trial court further erred in failing to respond to the jury's

question on this issue with an instruction that life imprisonment means

life without possibility of parole.

In making his argument, both in the trial court and

on appeal, Yarbrough asserts that the holding of Simmons should be

extended to all capital cases, and not limited to those in which the

prosecution relies on the aggravating factor of the defendant's future

dangerousness to society. See Simmons, 512 U.S. at 178, 114 S.Ct. 2187 (O'Connor,

J., concurring).

The Commonwealth contends that we have already

limited the application of the Simmons holding to those instances where

the defendant's future dangerousness is at issue and the defendant is,

in fact, parole-ineligible, citing, e.g., Roach v. Commonwealth, 251 Va.

324, 346, 468 S.E.2d 98, 105, cert. denied, 519 U.S. 951, 117 S.Ct. 365,

136 L.Ed.2d 256 (1996).

Thus, the Commonwealth asserts that we have declined

to extend the application of Simmons to a case where the defendant is

parole-ineligible, but where the Commonwealth relies solely on the

aggravating factor of the vileness of the crime.

The trial court accepted the Commonwealth's assertion

that this was “the present state of the law in Virginia” and refused to

grant the proposed instruction both prior to charging the jury and in

responding to the jury's inquiry on this issue.

The trial court correctly noted that this Court has

not heretofore applied the holding in Simmons beyond the specific

factual situation of that case. Indeed, following the United States

Supreme Court's decision in Simmons and the subsequent abolition of

parole in Virginia, we have not been presented with a capital murder

conviction in which a defendant sentenced to death by a jury was parole-ineligible

and the Commonwealth relied solely on the vileness aggravating factor,

rather than relying on that factor and future dangerousness or future

dangerousness alone.FN5

For example, Roach, cited by the Commonwealth, was

submitted to the jury solely on the future dangerousness aggravating

factor. Thus, we are presented with an issue of first impression. For

the reasons that follow, we hold that the trial court erred in failing

to grant the instruction requested by Yarbrough.

FN5. Cf. Cardwell, 248 Va. at 515, 450 S.E.2d at 155

(assuming issue of applicability where aggravating factor is vileness

was not moot, Simmons did not apply in any case because defendant was

not parole-ineligible). As we have noted, both parties rely on Simmons

as the principal basis for their respective positions on this issue.

Yarbrough contends that Simmons created a broad due process right “that

a jury be fully informed as to what the realities of a sentence are.”

The Commonwealth contends that Simmons is properly

limited to those cases where future dangerousness is at issue because

the possibility that a mistaken belief by the jury that the defendant is

eligible for early release from a life sentence would necessarily

prejudice the jury in favor of imposing the death penalty if the jury

believed the defendant posed a continuing threat to society. The

Commonwealth asserts that this prejudice is not invoked in the jury's

determination of the vile nature of a crime already committed.

We find neither of these views to be persuasive on

the issue we are called upon to address in this appeal. The Simmons

decision has no application to the present case because the defendant in

that case did not challenge a conviction premised solely on the

aggravating factor of vileness and, thus, the reliance of both parties

on the analysis in that case is misplaced. Simmons was decided under the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and in that decision the

United States Supreme Court established a minimum level of protection

applicable based upon a specific factual scenario.FN6

While Virginia courts are required to adhere to that

minimum standard, this Court must make its own determination about what

additional information a jury will be told about sentencing to ensure a

fair trial to both the defendant and the Commonwealth. In this context,

we agree that “the wisdom of the decision to permit juror consideration

of [post-sentencing events] is best left to the States.” California v.

Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 1014, 103 S.Ct. 3446, 77 L.Ed.2d 1171 (1983); see

also Simmons, 512 U.S. at 183, 114 S.Ct. 2187 (Scalia, J., dissenting).

FN6. One of the plurality opinions in Simmons would

have also applied the jury trial right of the Eighth Amendment in

mandating a “life means life” instruction. See Simmons, 512 U.S. at 172,

114 S.Ct. 2187 (Souter, J., concurring). Initially, we reject the

Commonwealth's contention that we have declined, even by implication, to

extend the rule in Simmons to a capital murder case where the defendant

was parole-ineligible and the Commonwealth relied solely on the

aggravating factor of vileness of the crime. Since the abolition of

parole in Virginia through the enactment of Code § 53.1-165.1, a jury

has imposed the death sentence only where the Commonwealth asserted the

defendant's future dangerousness to society.FN7

Thus, in every capital murder trial where future

dangerousness was an issue and the crime occurred on or after January 1,

1995, the defendant has been parole-ineligible if convicted, and the

trial courts of this Commonwealth have been required by Simmons to

instruct the jury on the defendant's ineligibility for parole where such

an instruction was requested by the defendant prior to the jury being

instructed or following a jury's question to the trial court on that

issue during deliberations.

Accordingly, in reviewing such decisions, we have

applied Simmons only under a factual scenario consonant with that

considered by the United States Supreme Court in that case.FN8 Compare

Wright v. Commonwealth, 248 Va. 485, 487, 450 S.E.2d 361, 363 (1994),

cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1085, 115 S.Ct. 1800, 131 L.Ed.2d 726 (1995) (finding

that defendant was not parole-ineligible) with Mickens v. Commonwealth,

249 Va. 423, 425, 457 S.E.2d 9, 10 (1995) (finding that defendant was

parole-ineligible and remanding for resentencing). Thus, since the

abolition of parole in Virginia, this appeal presents our first

opportunity to consider whether the granting of an instruction on parole

ineligibility is required in a capital case in which the Commonwealth

relied on the vileness aggravating factor alone.

FN7. Code § 53.1-165.1, in pertinent part, provides

that “[a]ny person sentenced to a term of incarceration for a felony

offense committed on or after January 1, 1995, shall not be eligible for

parole upon that offense.” Code § 53.1-40.01 provides for parole of

geriatric prisoners, but expressly excludes from its application

individuals convicted of capital murder, a class one felony. Similarly,

there is no possibility of parole from a sentence of death. Code §

53.1-151(B).In the following cases the defendants were parole-ineligible

and the jury imposed a sentence of death based upon both the future

dangerousness and vileness aggravating factors: Walker v. Commonwealth,

258 Va. 54, 515 S.E.2d 565 (1999); Hedrick v. Commonwealth, 257 Va. 328,

513 S.E.2d 634 (1999); Payne v. Commonwealth, 257 Va. 216, 509 S.E.2d

293 (1999); Kasi v. Commonwealth, 256 Va. 407, 508 S.E.2d 57 (1998),

cert. denied, 527 U.S. 1038, 119 S.Ct. 2399, 144 L.Ed.2d 798 (1999);

Swisher v. Commonwealth, 256 Va. 471, 506 S.E.2d 763 (1998); Walton v.

Commonwealth, 256 Va. 85, 501 S.E.2d 134, cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1046,

119 S.Ct. 602, 142 L.Ed.2d 544 (1998); Lilly v. Commonwealth, 255 Va.

558, 499 S.E.2d 522, cert. granted, 525 U.S. 981, 119 S.Ct. 443, 142

L.Ed.2d 398 (1998), judgment rev'd on other grounds, 527 U.S. 116, 119

S.Ct. 1887, 144 L.Ed.2d 117 (1999); Beck v. Commonwealth, 253 Va. 373,

484 S.E.2d 898, cert. denied, 522 U.S. 1018, 118 S.Ct. 608, 139 L.Ed.2d

495 (1997). In Jackson v. Commonwealth, 255 Va. 625, 499 S.E.2d 538,

cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1067, 119 S.Ct. 796, 142 L.Ed.2d 658 (1999), the

jury imposed the death sentence based solely upon a finding of future

dangerousness. In Reid v. Commonwealth, 256 Va. 561, 506 S.E.2d 787

(1998), the death sentence was imposed by the trial court following a

guilty plea based solely upon a finding of vileness; however, it is self-evident

that the concerns raised by Simmons and in this appeal are not present

where the sentence is imposed by the trial court.

FN8. In doing so, we have limited our application of

Simmons to the penalty-determination phase, rejecting attempts to expand

its application to other procedures during trial. See, e.g., Lilly v.

Commonwealth, 255 Va. 558, 567-68, 499 S.E.2d 522, 529-30 (1998), rev'd

on other grounds, 527 U.S. 116, 119 S.Ct. 1887, 144 L.Ed.2d 117 (1999)

(holding that Simmons does not require the trial court to “educate”

potential jurors on effect of parole ineligibility during voir dire).

There is no constitutional right, under either the

Constitution of Virginia or the United States Constitution, for a

defendant to have a jury determine his sentence. Fogg v. Commonwealth,

215 Va. 164, 165, 207 S.E.2d 847, 849 (1974). Nonetheless, where the

jury is delegated the responsibility of recommending a sentence, the

defendant's right to a trial by an informed jury requires that the jury

be adequately apprised of the nature of the range of sentences it may

impose so that it may assess an appropriate punishment. Cf. Commonwealth

v. Shifflett, 257 Va. 34, 43, 510 S.E.2d 232, 236 (1999). The underlying

concern is whether issues are presented in a manner that could influence

the jury to assess a penalty based upon “ ‘fear rather than reason.’ ”

Farris v. Commonwealth, 209 Va. 305, 307, 163 S.E.2d 575, 576 (1968) (quoting

State v. Nickens, 403 S.W.2d 582, 585 (Mo.1966)).

Where information about potential post-sentencing

procedures could lead a jury to impose a harsher sentence than it

otherwise might, such matters may not be presented to the jury. Thus, it

has long been held in this Commonwealth that it is error for the trial

court to instruct the jury that the defendant would be eligible for

parole or could benefit from an executive act of pardon or clemency.FN9

See, e.g., Hinton v. Commonwealth, 219 Va. 492, 496, 247 S.E.2d 704, 706

(1978); Jones v. Commonwealth, 194 Va. 273, 279, 72 S.E.2d 693, 696-97

(1952); Coward v. Commonwealth, 164 Va. 639, 646, 178 S.E. 797, 799

(1935).

FN9. As we have noted in prior opinions addressing

this issue, this rule is by no means universal, with many states taking

the position that such instructions are proper because a fully informed

jury is a right of both the defendant and the state. See Hinton v.

Commonwealth, 219 Va. 492, 495, 247 S.E.2d 704, 706 (1978). See

generally Annotation, Prejudicial Effect of Statement or Instruction of

Court as to Possibility of Parole or Pardon, 12 A.L.R.3d 832 (1967);

Annotation, Procedure to be Followed Where Jury Requests Information as

to Possibility of Pardon or Parole from Sentence Imposed, 35 A.L.R.2d

769 (1954).

This division of authority, however, merely lends

credence to the views expressed in Ramos and by Justice Scalia in

Simmons, supra. Unquestionably, it was this long-standing rule which

prompted the trial court's refusal of Yarbrough's proffered “life means

life” instruction and its response to the jury's question concerning the

meaning of a life sentence.

However, the present case presents the diametrically

opposite situation: a case where information about post-sentencing

procedures is needed to prevent a jury from imposing a harsher sentence

than it otherwise might render out of speculative fears about events

that cannot transpire. Accordingly, an examination in some detail of the

cases which established this rule is warranted and guides our further

analysis as to their continued application to capital murder

prosecutions in light of the abolition of parole under Code §

53.1-165.1.

In Coward, the jury in a drunk driving case made a

specific inquiry as to “what time the defendant would get off while he

was confined in jail.” 164 Va. at 643, 178 S.E. at 798. The trial court

responded to this query by detailing for the jury the then applicable

rules for “good behavior” reduction of a sentence. Id. We held that this

was error and that “[t]hese jurors should have been told that it was

their duty, if they found the accused guilty, to impose such sentence as

seemed to them to be just. What might afterwards happen was no concern

of theirs.” Id. at 646, 178 S.E. at 800.

This language from Coward has become the standard

charge to a jury whenever an inquiry is made regarding the possibility

of a defendant being paroled, pardoned, or benefited by an act of

executive clemency.

In Jones, after determining that the defendant was

guilty of first-degree murder, the jury inquired whether “if they gave

him life imprisonment ... they would have any assurance that the

defendant would not ‘get out.’ ” Jones, 194 Va. at 275, 72 S.E.2d at

694. The trial court responded that “it could not give that assurance;

that would be in the hands of the executive branch of the government.”

Id. The jury imposed a sentence of death on Jones. We reversed that

sentence.

Noting that under the law then applicable, a

defendant sentenced to life imprisonment for first-degree murder was not

eligible for parole, this Court asked rhetorically “who can say that the

verdict here would have been rendered had the jury been told that the

defendant could not be paroled after a sentence of life imprisonment and

would not ‘get out’ unless pardoned by the governor?” Id. at 278-79, 72

S.E.2d at 696. Accordingly, we held that the trial court's instruction

was erroneous because “it did not fully inform the jury upon the point

to which their inquiry was directed.” Id. at 278, 72 S.E.2d at 696.

Nonetheless, because the defendant would have been

subject to parole if sentenced to a lesser term of years, or to pardon

in any case, in giving instructions to the trial court for the remanded

trial the majority adhered to the rule announced in Coward in order to

avoid having the jury base its sentence “on speculative elements, rather

than on the relevant facts of the case, [since this] would lead

inevitably to unjust verdicts.” Id. at 279, 72 S.E.2d at 697.

Concurring, Justice Spratley, joined by Justice Smith,

opined that the defendant was prejudiced by the trial court's failure to

inform the jury, as the defendant had requested, that if given a

sentence of life imprisonment he would not be eligible for parole. Id.

at 282, 72 S.E.2d at 698 (Spratley, J., concurring). Moreover, Justice

Spratley opined that the failure to properly instruct the jury would

inevitably result in juror confusion and “a reaction, just as likely

against the accused as in his favor.” Id. at 281, 72 S.E.2d at 698.

Asserting that the view expressed by the majority of

other states at that time was that the jury could best perform its duty

when given full knowledge of the possible consequences of the law,

Justice Spratley concluded that “had such information been given [to the

jury] in simple and direct language” no prejudice would have resulted.

Id. at 283, 72 S.E.2d at 698.

The most succinct statement of the policy behind the

rule announced in Coward is to be found in our subsequent decision in

Hinton. In that case, the trial court responded to a jury's question

concerning parole by instructing the jurors that “early release [of

prisoners] is not for the Court or jury to be concerned about.” Hinton,

219 Va. at 494, 247 S.E.2d at 705. However, the trial court then

described the manner under which early release might occur and told the

jury that “[s]ometimes people never serve their entire sentence.” Id.

The trial court concluded by stating that it “would

like to advise [the jury] about the probability of early release, but

I'm not allowed to tell you what it is in order that you may take it

into consideration when you fix punishment.” Id. at 494-95, 247 S.E.2d

at 705. Following this instruction, the jury returned in only five

minutes with a verdict imposing the maximum sentence possible for the

defendant's offense. Id. at 495, 247 S.E.2d at 706.

Rejecting the Commonwealth's argument that the trial

court's statement comported with the holdings in Coward and Jones, we

reversed Hinton's conviction. Noting that the issue was still a matter

of serious contention among the states, we stated that “Virginia is

committed to the proposition that the trial court should not inform the

jury that its sentence, once imposed and confirmed, may be set aside or

reduced by some other arm of the State.” Hinton, 219 Va. at 495, 247 S.E.2d

at 706 (citing Coward, 164 Va. at 646, 178 S.E. at 799-800) (emphasis

added). Rejecting the Commonwealth's contention that the trial court's

error was not sufficiently prejudicial to warrant reversing the

conviction, we stated the policy underlying our continued adherence to

the rule from Coward as follows:

[T]he jury's question would have been necessary only

if one or more of the jurors contemplated voting for a sentence less

than the maximum; the inquiry would have been superfluous if the jury

had already decided to assess [the maximum penalty]. Thus, as a result

of the improper emphasis on post-verdict procedures ... it [is] likely

that some member of the jury, influenced by the improper remarks, agreed

to fix the maximum penalty, when he or she otherwise would have voted

for a lesser sentence. Consequently, prejudice to the defendant is

manifest. 219 Va. at 496-97, 247 S.E.2d at 706-07.

In sum, the policy underlying the rule first

announced in Coward, and subsequently affirmed in Hinton, is that the

jury should not be permitted to speculate on the potential effect of

parole, pardon, or an act of clemency on its sentence because doing so

would inevitably prejudice the jury in favor of a harsher sentence than

the facts of the case might otherwise warrant.

This prejudice to the defendant was manifest in

Hinton, where the jury was required to fix punishment at a specific term

of years, and in Jones, where the jury could elect between a sentence of

death, of life imprisonment without possibility of parole, or a term of

years from which the defendant might be paroled after a time. We have

upheld the rule from Coward and its progeny in capital murder cases

where the defendant would have been eligible for parole if given a life

sentence. See, e.g., Stamper v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 260, 278, 257 S.E.2d

808, 821 (1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 972, 100 S.Ct. 1666, 64 L.Ed.2d

249 (1980).

As we have noted above, the present case presents the

converse situation. It is manifest that the concern for avoiding

situations where juries speculate to the detriment of a defendant on

post-sentencing procedures and policies of the executive branch of

government requires that the absence of such procedures or policies

favoring the defendant be disclosed to the jury.

Where a defendant is convicted of capital murder in a

bifurcated jury trial, in the penalty-determination phase of the trial

the jury must select solely between a sentence of life imprisonment

without possibility of parole or one of death. The Coward rule simply

does not address that unique situation.

This unique situation arises from the fact that a

defendant sentenced to life imprisonment for capital murder, a class one

felony, is not subject to “geriatric parole.” See note 7, supra.

Accordingly, while we recognize that the limitations placed upon the

availability of parole by Code §§ 53.1-40.01 and 53.1-165.1 may call

into question the continued viability of the Coward rule in a

non-capital felony case, as where, for example, a defendant subject to a

maximum term of years for a specific crime would serve that entire

sentence before being eligible for geriatric parole, we emphasize that

our decision today is limited to the effect of Code § 53.1-165.1 on

capital murder prosecutions.

Undeniably, in the specific circumstance where the

jury must select between only two sentences: death and life imprisonment

without possibility of parole, the jury's knowledge that a life sentence

is not subject to being reduced by parole will cause no prejudice to the

defendant, and may work to his advantage. It is equally clear that

without this knowledge the jury may erroneously speculate on the

possibility of parole and impose the death sentence.FN10

If the jury is instructed that the defendant's parole

ineligibility is a matter of law and not one of executive discretion,

there is no possibility that the jury would speculate as to whether “its

sentence ... imposed and confirmed may be set aside or reduced by some

other arm of the State.”

On the other hand, without this knowledge, there is a

very real possibility that the jury may erroneously speculate on the

continuing availability of parole. The real danger of this possibility

is amply demonstrated by the jury's question in this case in which the

jurors posited the hypothetical situation that Yarbrough might serve as

few as twelve years of a life sentence.

FN10. These conclusions arise not merely from

reasoned logic, but have been repeatedly confirmed through empirical

research. Indeed, that research was cited in Simmons, 512 U.S. at

172-74, 114 S.Ct. 2187 (Souter, J., concurring), and serves as the basis

for a plurality of the United States Supreme Court continuing to urge

expansion of the Simmons rule. See, e.g., Brown v. Texas, 522 U.S. 940,

940-41 and n. 2, 118 S.Ct. 355, 139 L.Ed.2d 276 (1997) (Stevens, J.,

dissenting) (four justices dissenting from denial of certiorari).

We note that in Brown, Justice Stevens observed that

“the likelihood that the issue [of expanding the application of Simmons]

will be resolved correctly may increase if this Court allows other

tribunals ‘to serve as laboratories in which the issue receives further

study before it is addressed by this Court.’ ” Id. at 943 (citation from

footnote omitted). [13]

In short, whereas in the circumstances presented in

some prior cases the availability of parole was not a proper matter for

jury speculation because it might lead to the unwarranted imposition of

harsher sentences, in the context of a capital murder trial a jury's

knowledge of the lack of availability of parole is necessary to achieve

the same policy goals articulated in Coward and Hinton. Moreover, a jury

fully informed on this issue in this context is consistent with a fair

trial both for the defendant and the Commonwealth.

Accordingly, we hold that in the penalty-determination

phase of a trial where the defendant has been convicted of capital

murder, in response to a proffer of a proper instruction from the

defendant prior to submitting the issue of penalty-determination to the

jury or where the defendant asks for such an instruction following an

inquiry from the jury during deliberations, the trial court shall

instruct the jury that the words “imprisonment for life” mean

“imprisonment for life without possibility of parole.” FN11 Because the

trial court refused such an instruction, Yarbrough was denied his right

of having a fully informed jury determine his sentence.

FN11. We emphasize that the defendant must request

the instruction. The trial court is not required to give the instruction

sua sponte. Cf. Peterson v. Commonwealth, 225 Va. 289, 297, 302 S.E.2d

520, 525, cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865, 104 S.Ct. 202, 78 L.Ed.2d 176

(1983). [14] Finally, we must consider whether the comments concerning

the effect of a life sentence made by Yarbrough's counsel during closing

argument render harmless the prejudice resulting from the trial court's

failure to instruct the jury on the issue of Yarbrough's parole-ineligible

status. FN12

The Commonwealth contends that Yarbrough adequately

addressed this issue to the jury in his closing argument and, therefore,

Yarbrough was not prejudiced.FN13 We disagree.

FN12. We have previously held that in consideration

of the United States Supreme Court's decision in Caldwell v. Mississippi,

472 U.S. 320, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 86 L.Ed.2d 231 (1985), the Commonwealth is

barred from commenting on the power of the trial court and this Court to

set aside a jury's sentence of death since such statements might “lead[

] a jury to believe the sentencing responsibility lies ‘elsewhere’.”

Frye v. Commonwealth, 231 Va. 370, 397, 345 S.E.2d 267, 285 (1986).

Nothing in the view we express herein should be interpreted as

diminishing that holding.

FN13. In Williams v. Commonwealth, 234 Va. 168,

178-79, 360 S.E.2d 361, 367-68 (1987), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 1020, 108

S.Ct. 733, 98 L.Ed.2d 681 (1988), relying on Hinton, we held that a

parole-ineligible defendant was not entitled to “argue the meaning of a

life sentence” because “the jury is not to be concerned with what may

later happen to a defendant sentenced to the penitentiary, [and] no

inference can be drawn or argued one way or the other as to whether he

will serve his full term.” Id. at 179, 360 S.E.2d at 368. In light of

the view expressed by a plurality of justices in Simmons, 512 U.S. at

178, 114 S.Ct. 2187 (O'Connor, J., concurring), that the issue of parole

ineligibility may be addressed in argument, our holding in Williams has

clearly been called into question.

Yarbrough's counsel argued that “[l]ife is life ... [h]e

will spend a long time in prison” and made other similar comments during

the closing argument which implied that Yarbrough would be ineligible

for parole. Clearly, as indicated by its subsequent inquiry to the trial

court, the jury did not accept counsel's assertions as to the law.

Accordingly, we cannot say that Yarbrough was not prejudiced by the

trial court's failure to respond to the jury's question with the

appropriate instruction as Yarbrough had requested. Therefore, the death

sentence in this case will be vacated.

E. Sentence Review

In view of our ruling that the sentence of death will

be vacated on other grounds, we will not conduct the sentence review

provided by Code § 17.1-313(C) to determine whether that sentence was

imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other

arbitrary factors or whether the sentence is excessive or

disproportionate to the sentences imposed in similar cases.

IV. CONCLUSION

For the reasons assigned, we will affirm Yarbrough's

conviction of capital murder, vacate the death sentence, and remand the

case for a new penalty-determination phase. We will affirm Yarbrough's

robbery conviction and sentence of life imprisonment. Record No. 990261-

Affirmed in part, sentence vacated, and case remanded. Record No.

990262- Affirmed.

*****

COMPTON, Justice, with whom Chief Justice CARRICO

joins, dissenting in part.

I agree that Yarbrough's conviction of capital murder

should be affirmed. I disagree, however, that his death sentence should

be vacated and the case remanded for redetermination of the capital

murder penalty.

The majority holds that in the penalty phase of a

trial when the defendant has been convicted of capital murder, either

upon the defendant's tender of a proper instruction prior to submitting

the issue of penalty to the jury or upon the defendant's request for

such an instruction following an inquiry from the jury during

deliberations, the trial court shall instruct the jury that the words

“imprisonment for life” mean “imprisonment for life without possibility

of parole.” This viewpoint, based upon the idea of having a “jury fully

informed,” even on matters not relevant for jury consideration, amounts

to an unwise change in the landscape for trial of capital murder cases

in Virginia when the crime meets the vileness aggravating factor.