Graham Young, the St. Albans Poisoner

By Johnny Sharp - CrimeLibrary.com

Mystery Illness

During the summer of 1961, a strange virus seemed to be spreading

through a small family home in a northern suburb of London, England.

Since February, 37-year-old Molly Young had suffered vomiting, diarrhea

and excruciating stomach pain, which she initially dismissed as bilious

attacks. Before long her husband Fred, 44, was also suffering, with

similar stomach cramps debilitating him for days at a time. Then Fred's

eldest daughter Winifred, 22, was violently ill on a couple of occasions

that summer. Shortly afterwards, her brother Graham Young was violently

sick at home.

It even seemed as if the mystery bug had spread beyond their household -

a couple of Graham's school friends had also been off school ill a

couple of times with similar painful symptoms.

In November 1961 the plot thickened. Winifred Young was served a cup of

tea by her brother one morning, but found its taste so sour she took

only one mouthful before she threw it away. While on the train to work

an hour later, she began to hallucinate, had to be helped out of the

station and was eventually taken to hospital, where doctors came to the

conclusion that she had somehow been infected with the rare poison

belladonna. She told her father Fred, who developed a theory. His

14-year-old son Graham had been crazy about chemistry for some years,

and had even been banned from using chemicals in the house after

abortive experiments set fire to furniture in his room. Could the boy

have inadvertently contaminated his family's food?

He confronted his son, but Graham blamed Winifred, who he claimed had

been using the family's teacups to mix shampoo.

Unconvinced, Fred searched Graham's room, but found nothing

incriminating. Nevertheless, he warned his son to be more careful in

future when "messing about with those bloody chemicals."

The family had been concerned about Graham for a while. He was

just...different, utterly unlike other boys his age. Since the age of 9

or 10, when he started stealing his stepmother Molly's perfume and nail

varnish remover to analyze its contents and sniff the vapors, he'd been

obsessed with chemistry and poisons. If a member of the family took a

headache tablet or some cough medicine, he would take great pleasure in

telling them the exact scientific names for all the ingredients, and

seemed especially keen on telling them in detail what agonies would

befall them if they took a very large dose.

Still, a boy's got to have a hobby, so when Graham scraped through his

"11 plus" exams (which determined in those days whether a child would go

to a grammar school for more academically minded children, or a

"secondary modern" for those of a more practical bent), his father

bought him a chemistry set as a reward. He wasn't to know that by this

stage of his son's self-education, it was equivalent to giving a Cordon

Bleu chef a couple of pots and a beginner's cook book.

With the help of library books, Graham had already gained the expertise

of a chemistry post-graduate. Yet his do-it-yourself chemistry

experiments seemed to be a touch more extreme than you might expect even

from the most inquisitive schoolboy. He had graduated from nail varnish

remover to inhaling from a bottle of ether to get high. He carried a

bottle of acid around with him which once burnt a hole in his school

blazer. On other occasions he would extract gunpowder from fireworks to

make small bombs. He blew up his neighbor's wall and a nearby hut, but

managed to escape blame for the incidents.

Although Fred Young had never been particularly close to his son, even

he couldn't entertain the idea that his own flesh and blood could be

deliberately poisoning the family.

If he'd known how his wife's symptoms would suddenly worsen a few months

later, he might have had second thoughts.

'The Mad Professor'

Graham Young was born September 7, 1947, to Margaret Young, but his

mother had developed pleurisy during pregnancy, and although the child

was perfectly healthy, Margaret died of tuberculosis only three months

after her son's birth. Her husband Fred, a machine setter, was

devastated by her death, and found it difficult to cope with bringing up

his daughter Winifred, then aged 8, as well as the new baby. Graham went

to live with his Aunt Winnie, who lived nearby, while his sister was

taken in by her grandmother. Graham became very close to Winnie and her

husband Jack, and hated any separation from them.

Then when he was two and a half Graham's father married again, to Molly,

and the family was reunited with their new stepmother in a house on

London's busy North Circular Road.

Although we may speculate about the effect these early upheavals may

have had on the boy, for reasons that are still fairly unfathomable,

Graham Young soon showed signs that he was a very unusual child indeed.

It's perfectly normal for children to idolize certain individuals, be

they famous sportsmen or celebrities, or even older friends or family

members. But Graham Young chose some unlikely figures as his boyhood

role models. He voraciously read books about murderers such as Dr.

Crippen, and he would pore over a book called "Sixty Famous Trials," his

favorite chapter of which told the story of William Palmer, the

Victorian doctor who poisoned his wife and several others with antimony.

As well as these rather unsavory heroes, by the age of 12 the boy would

tell anyone who would listen about his admiration for Adolf Hitler, and

how the Nazi leader was a much maligned figure. Soon after that he began

boasting about his interest in the occult, and claimed to be part of a

local coven run by a man he had met in the local library.

He was a solitary child, with few friends. Most of his schoolmates kept

their distance, finding him "creepy," and teachers were hardly any

keener on him, disturbed by his habit of wearing an old swastika badge

to school, at a time when World War II was still all too fresh in the

memory for many.

He showed little interest in most school subjects, with the notable

exception of chemistry, and particularly toxicology, or the study of

poisons, for which he displayed a fascination bordering on obsession.

That said, he was mainly self-taught, spending long hours in the library

reading books on poisons and forensic science.

Those children who did briefly play with young Graham told of how he

would try to get them to sniff ether with him, and also involve them in

his occult ceremonies, on one occasion sacrificing a neighborhood cat.

In fact around that time several such feline residents of the area went

missing, suggesting this was by no means a unique incident.

Although Winifred Young writes in her book "Obsessive Poisoner" that

Graham grew to enjoy a close and affectionate relationship with his

stepmother, Molly, the boy himself often told classmates how much he

hated her. He would show them a small plasticine voodoo doll he had

made, full of pins, which he carried around claiming it represented his

stepmother. Later he would tell psychiatrists that he often dreamed of

how much happier his life might have been if only his real mother had

lived. Part of this resentment may have simply been down to the fact

that Molly was a strict parent to Graham, and after she confiscated a

dead mouse he had poisoned, he drew a picture of a tombstone, on which

were written the words "In Hateful Memory of Molly Young, RIP." He then

deliberately left it out where she would see it.

Yet Molly Young was not the first subject chosen for Graham's first

life-endangering "experiments" with poison. His interest in chemistry

had helped him befriend a fellow science enthusiast, a boy named

Christopher Williams, who was also a neighbor of the Young family. The

pair would often eat their packed lunches together at school, and

sometimes swap sandwiches. Before long Williams began to suffer regular

bouts of sickness, headaches and painful cramps. His mother didn't know

what to think, wondering whether this might simply be a case of childish

play-acting. Doctors could only suggest that his symptoms, since they

involved headaches and vomiting, were those of severe migraine. The

possibility of one of his school friends poisoning him would surely have

seemed far-fetched even if it had crossed their minds, since the pair

were only 13 and not old enough to obtain poisons.

What they didn't account for was the exceptional cunning of

Christopher's new friend. After talking knowledgeably about poisons and

convincing two separate local chemists that he was aged 17 and needed

them for study, Graham Young had obtained enough antimony, arsenic,

digitalis and thallium to kill 300 people.

Still, he was relatively restrained in the doses he gave to Williams,

and they even appeared to have a motive in some cases. For instance, on

one occasion Williams told Young he was taking a girl they both liked

out on a date to a TV show recording that Friday evening. Conveniently

for Young, Williams was violently ill that day, and Graham went in his

place. Still, even though the pair had once had a playground fight in

which Young vowed "I'll kill you for this," Williams never suspected

that his friend's obsession with poisons had anything to do with his

recurring illness. Besides, Graham did a good impression of concern, and

watched his friend's extreme discomfort with great fascination,

expressing his sympathies, while also predicting the likely next step

his illness would take. With friends like that, who needs enemies?

Other pupils of the John Kelly Secondary School were more wary of the

cold, eccentric Young. They nicknamed him "the mad professor," a label

that was not intended to be affectionate, but which Young seemed to

like. Clive Creager, a friend of William, recalled the macabre drawings

Young would show him. "I would be hanging from some gallows over a vat

of acid," he told Anthony Holden, author of "The St. Albans Poisoner,"

"with syringes marked 'poison' sticking into me. He was evil and I was

afraid of him."

Mercifully for the likes of Creager and Williams, though, Graham found

his school friends ultimately unsatisfactory as human guinea pigs, since

he couldn't keep tabs on their symptoms once they were absent from

school due to illness. So he reserved his most daring and dangerous

experiments for a group of patients whose progress he could observe at

closer quarters -- his own family.

Death in the Family

Molly Young's illness got progressively worse during the early months of

1962. She lost weight, suffered excruciating back ache, and her hair

began to fall out. She also appeared to age noticeably, and Winifred

Young later wrote, "It was as if she was wasting away in front of our

eyes."

When Molly Young woke up on Easter Saturday, 1962, however, her symptoms

seemed different. Her neck felt stiff, and she had "pins and needles" in

her hands and feet. Nevertheless she went out shopping, but returned

before lunchtime, while Fred Young was out at the local pub. Her husband

came home to find Graham staring out of the kitchen window, watching

awestruck as his stepmother writhed in agony in the back garden. She

died in hospital later that day.

Molly Young was cremated at Graham's suggestion, after the pathologist

concluded that death was due to the prolapse of a bone at the top of her

spinal column. This is a known symptom of long-term antimony poisoning,

and yet no connection was made. The most popular conclusion among the

family was that her injury was connected to a bus crash she had been

involved in the previous year when she received a blow to the head. In

fact it turned out that the problem with the spinal column was probably

not the cause of death. Holden explains that Young changed his choice of

poison because after more than a year of being regularly dosed Molly had

actually developed a tolerance to antimony. On the evening before she

died, he had spiked her evening meal with 20 grains of the colorless,

odorless, tasteless "heavy metal" substance thallium. He rather overdid

it -- there was enough in there to kill five or six people.

Even after Molly's death, the Young family's mystery illness appeared to

be spreading - Graham's uncle John began to vomit copiously after the

funeral. Must have been something he ate...such as the pre-spiked

mustard pickle provided for the sandwiches, which only he ate.

By this time Young's second major experiment cum murder plot was well

under way. And this time the victim was actually his own flesh and

blood.

Fred Young had suffered attacks of vomiting, diarrhea and stomach pains

now and again throughout Molly's illness, but after her death the

symptoms intensified to such a point that he became convinced he was

about to die. When he was admitted to hospital Graham frequently visited

him, and enthusiastically discussed his condition with doctors, who

couldn't work out if it was arsenic or antimony poisoning. The latter

was eventually diagnosed, and doctors estimated that one more dose could

have killed him. Fred Young later reflected that his bouts of sickness

always seemed to happen on a Monday, the day after Graham would

accompany him to the local pub on Sundays.

While that thought only struck him after his son's arrest, during his

time in hospital Fred told his daughter not to bring Graham to see him

any more. If that betrays a suspicion on his part that his son was

poisoning the family, the whole family and several of Graham's friends

shared those fears, but just as before, the idea that a 14-year-old boy

could be coldly attempting to torture and kill his own family seemed too

horrendous to even contemplate, let alone voice in public.

It fell to a more emotionally detached figure to finally raise the

alarm. Graham's school chemistry teacher, Geoffrey Hughes, had long been

uneasy about the increasingly extreme experiments Young was insisting on

performing, and one night after school he searched the boy's desk. After

finding bottles of poisons, drawings of dying men, and essays about

famous poisoners, he contacted the police.

To try and ascertain his mental state, Young was sent for what he

thought was a careers interview, wherein the interviewer (in reality a

police psychiatrist) appealed to his vanity and persuaded him to talk at

length about his expertise with poisons.

The "careers officer" reported his horrified findings, but when the

police stepped in Graham denied everything, even when a phial of

antimony which he carried around with him (often referring to it as "my

little friend"), fell from his shirt pocket. Eventually, though, he

broke down and confessed all, finally leading police to his several

caches of poisons, stashed in a hedge near his home, and in the same hut

across the road which he once blew a hole in with his gunpowder

experiments.

"It grew on me like drug habit," he said of his murderous hobby, "except

it was not me who was taking the drugs."

Broadmoor's Youngest Inmate

Despite the fact that there was insufficient evidence to try the

14-year-old Young for the murder of his step mother, he was convicted of

poisoning his father, sister and friend Chris Williams, and the verdict

found there was "a lack of moral sense" at the heart of his personality.

These days we might be tempted to label such character traits as

"psychopathic." He was sent to Broadmoor maximum security hospital with

an order that he was not to be released without the permission of the

Home Secretary for 15 years. He would be Broadmoor's youngest inmate

since 1885.

While on remand awaiting trial, he was already telling psychiatrists, "I

miss my antimony. I miss the power it gives me." Where there's a will,

though, there's a way, and within a few weeks of his arrival at

Broadmoor, a fellow prisoner named John Berridge had died of cyanide

poisoning. This was the same Berridge that Winifred Young says Graham

complained about in letters, expressing irritation at his loud snoring

in the communal dorms. Nevertheless, the authorities were baffled, as

there was no cyanide to be found anywhere in the prison. Young then

corrected them, patiently explaining how cyanide could be extracted from

laurel bush leaves, of which there were copious amounts in adjoining

fields. But his confession was only one of many, as tends to be the case

whenever someone dies in a mental institution, so the official verdict

was suicide.

On another occasion the staff's coffee was found to contain harpic

bleach from the toilets. From then on, staff would joke to inmates,

"Unless you behave, I'll let Graham make your coffee."

Meanwhile, Young was still pursuing familiar interests. According to the

British crime monthly Murder Casebook, he grew a Hitler moustache and

making hundreds of wooden swastikas to wear round his neck. These hardly

appear to be the actions of a man anywhere near being cured of whatever

mental illness had afflicted his young mind. But Graham Young's doctors

were confident that in time he would grow out of these adolescent

obsessions.

Their hopes appeared to have been fulfilled by the end of his fifth year

inside, as he had become a model prisoner, and was moved into a less

strict block with more freedoms. It was suggested to Young that he might

one day be able to pursue a university degree if he "got better," which

appeared to convince him to go cold turkey on his toxicology addiction.

Despite this, it was later revealed by Broadmoor contemporaries of Young

that as late as 1968, nearly six years into his sentence, two whole

packets of "sugar soap," a cleanser used to wash down the walls before

painting, went missing, and the contents were later found in the

communal tea urn. Potentially, no fewer than 97 people could have had

their stomachs burnt out, and many might well have died. Clearly Young's

desire to convince the authorities of his rehabilitation was soon

disregarded once he was presented with such a golden opportunity to

poison those around him. In Broadmoor, however, the unwritten rules of

prison life applied, which meant the fellow prisoners who discovered

what had happened refused to inform on Young to the authorities, but

instead meted out their own physical punishment in private.

In June 1970, after nearly eight years in Broadmoor, Dr. Edgar Udwin,

the prison psychiatrist, wrote to the home secretary to recommend his

release, announcing that Young "is no longer obsessed with poisons,

violence and mischief."

Young was thrilled, and Winifred Young tells of a letter he sent her

breaking the news of his impending release. "Your friendly neighborhood

Frankenstein will soon be at liberty," he joked. One of Young's nurses

had cause to question the wisdom of letting this man walk the streets.

Not long before his release he told her: "When I get out, I'm going to

kill one person for every year I've spent in this place." Incredibly,

this apparently sincere comment never reached the ears of the relevant

authorities, despite being taken down on file at the time.

'Diabolical Pains'

For all his "Frankenstein" jokes, Winifred Young was delighted to hear

of her brother's "full recovery," and eagerly awaited his release from

Broadmoor. She was happy to accept the authorities' view that he had

been cured, even if she later admitted there was an element of wishful

thinking at work. Fred Young was less thrilled, however, still finding

it hard to forgive his son for the death of his beloved wife, not to

mention the permanent damage Graham had inflicted on him. So when Graham

stepped out of the prison gates on February 4th 1971, he went to stay

with Winifred and her new husband Dennis in Hemel Hempstead, 40 miles

north-west of London. Despite their worries, their food remained

uncontaminated, although Graham was still insistent on extolling the

virtues of Adolf Hitler, and on this occasion ranted on about a "final

solution" style approach to the troubles in Northern Ireland, which were

reaching a peak around that time. "Cured" he may have been. A deeply odd

individual he remained.

According to Winifred Young, one of the first things her now 23-year-old

brother did on his release was to make a 'sentimental journey" to the

chemists where he had originally obtained his poisons. He proudly

announced his identity to staff there, hoping his notoriety may have

stood the test of time. He also returned to his old family home in

Neasden, introducing himself to neighbors he had known as a teenager. He

even visited his old school headmaster. Tellingly, he seemed much keener

to remind them of his notorious past crimes than to boast about his

rehabilitation.

Within a week of his release, Young began training as a storekeeper in

Slough, and moved into a hostel nearby. Soon after his arrival, though,

fellow hostel resident Trevor Sparkes, 34, began to experience sharp

abdominal cramps and sickness. Graham suggested a glass of wine might

help. That only seemed to make his symptoms get worse. His face swelled,

and the vomiting increased, along with diarrhea and strange scrotal

pains. Eventually Sparkes, an avid soccer player, was taken ill during a

game when he seemed to lose control of his legs. Doctors couldn't find a

satisfactory explanation, but he would continue feeling what he

described as "diabolical pains" for years afterwards, and never played

soccer again. Around the same time another man claimed to have had a

drink with an intense young fellow obsessed with chemicals and poisons,

and later committed suicide because of the incessant pain he

experienced. Whether he was effectively Graham Young's second (or even

third, if we count the Broadmoor cyanide incident) victim will surely

never be proved.

Shortly afterwards, Young got a job as a store clerk at a photographic

firm in Bovingdon, Hertfordshire, not far from his sister's home in

Hemel Hempstead. When they asked for references, they were referred to

the Broadmoor psychiatrist Dr Udwin, who wrote back assuring them that

although Young had suffered "a deepgoing personality disorder," he had

now made "an extremely full recovery." No mention of his erstwhile

predilection for poisons, which might have been relevant considering

highly toxic chemicals were used on the company premises.

The Bovingdon Bug

As it turned out, the new recruit at John Hadland Ltd. had no need to

avail himself of the substances available on site. He had already been

to London armed with the same fake ID of "M.E. Evans" that he had used

as a teenager, and bought a new batch of "antimony potassium tartrate"

(the full name by which he insisted on calling it) and thallium from a

West End chemist. Within days of starting work at Bovingdon, the new boy

happily accepted the job of making tea for his workmates.

The first colleague Young made friends with was 41-year-old Ron Hewitt,

who was soon to leave the firm but had stayed on for a few weeks to show

the new boy the ropes so he could take over his job.

Two older members of staff, 59-year-old storeroom manager Bob Egle and

60-year-old stock supervisor Fred Biggs, also befriended Young, lending

him cigarettes and money for his bus fare. However, after a time Egle

began to spend periods off work ill. Around the same time, Ron Hewitt

developed diarrhea, sharp stomach pains and a burning sensation in the

throat after drinking a cup of tea fetched by Young. The symptoms lasted

a few days, but doctors could only suggest food poisoning or gastric

flu. When he was well enough to return to work, though, the symptoms

promptly returned, invariably after drinking tea. Over the next three

weeks he suffered no fewer than twelve bouts of this mysterious illness.

After leaving the company Hewitt had no further symptoms, while Bob Egle

also recovered after a holiday. However, the day after returning to

work, Egle's fingers went numb, and he couldn't move without agonizing

pain. By the time he was taken to hospital, numbness had spread through

his body until he was virtually paralyzed, and unable to speak. To the

horror of his workmates, he died 10 days later, on July 7, 1971. The

cause of death was officially bronchial pneumonia arising from an

unusual type of polyneuritis known as the "Guillan-Barre syndrome."

"It's very sad," said Graham to colleagues, "that Bob should have come

through the terrors of Dunkirk (a crucial battle of World War Two) only

to fall victim to some strange virus." Such was Young's very vocal

concern, he was chosen to accompany the firm's managing director to the

cremation.

In the weeks following Egle's death, the staff at Bovingdon tried to put

the tragic incident behind them. Yet the rather work-shy young storeroom

assistant insisted on continually musing about possible medical causes

for Bob Egle's bizarre symptoms. Then in September 1971 Fred Biggs also

began to suffer the same symptoms. And he wasn't the only one.

Young's fellow storeroom worker Jethro Batt, 39, was made a cup of

coffee by Graham one evening, but threw it away complaining it tasted

bitter. "What's the matter?" asked Young. "D'you think I'm trying to

poison you?" 20 minutes later Batt vomited and felt intense pain in his

legs. Fellow staff members Peter Buck and David Tilson also suffered. In

the case of Batt and Tilson, their hair fell out, leaving the latter, as

doctors described him, "looking like a three-quarter plucked chicken."

Young had administered various doses of different poisons among his

workmates, designed to confuse doctors looking for a common cause of the

complaints. These manifested themselves in a number of unlikely ways. A

receptionist, Mrs. Diana Smart, complained of suffering from foul

smelling feet for months, while Buck and Tilson were rendered impotent

for some weeks after their initial illness. "I was going around with

several girls at the time," Tilson later related in court, "and I became

useless in bed."

Their ailments were put down to some kind of virus in the local area,

which became known as "the Bovingdon Bug." By unfortunate coincidence, a

stomach bug had spread among the village children on a couple of

occasions in the preceding months. Many workers speculated, just as the

residents of Neasden had a decade before, that a contaminated water

supply might be the cause. Others suspected radioactivity from

experiments in a nearby airfield could be the culprit.

If this was the same virus that had spread among the village's children,

it had certainly assumed a virulent new form. After briefly recovering

from his first experience of Young's unique approach to coffee-making,

Jethro Batt fell ill again, and after a few days he was in such pain he

later said he contemplated suicide. He remained in hospital for some

weeks.

Fred Biggs' condition was the worst of the new outbreak. His condition

deteriorated to the point where his skin began to peel off, and the pain

was such that he could not stand the weight of a bed sheet on his body.

Even that was not serious enough for Young's liking, it appears. "'F'

(Fred) is responding to treatment," he was later discovered to have

written in his diary. "He is being obstinately difficult. If he survives

a third week he will live. I am most annoyed."

Young's pessimism was misplaced. On November 19 death finally came to

Fred Biggs, as merciful release.

The Germ Carrier

By this time speculation as to what was causing "the Bovingdon bug" had

understandably reached fever pitch. Winifred Young writes that Diana

Smart even confided in the firm's Managing Director, Godfrey Foster,

that she suspected Graham Young was "a germ carrier." Alas, the only

suggestion she could make as to how he might have caught such "germs"

was that he lived in a boarding house with a Pakistani family.

On the afternoon that Fred Biggs' death was announced, the firm's doctor

gathered the staff to a meeting to reassure them that there was no

evidence that any lack of hygiene on the company premises could have

caused the deaths and illnesses. Yet one man wanted to know more. The

doctor was surprised to find himself being grilled by the young store

assistant, who asked several detailed questions as to why poisoning by

the heavy metal thallium had been ruled out. The doctor was puzzled by

his apparent in-depth knowledge of the subject, and told the firm's

owner. He in turn informed the police.

It's perhaps not so surprising that doctors took a while to consider

thallium poisoning as a cause of the outbreak, because until Graham

Young used it, it had never been used as a poison in Britain. Death from

gradual thallium poisoning is an agonizing affair, something which

Graham Young knew only too well. As well as suffering excruciating

stomach pains, violent sickness and diarrhea, patients often lose their

hair (as did Batt and Tilson, and Young's stepmother Molly years before)

and suffer thickening and scaliness of the skin. Later, degeneration of

the nerve fibers sets in, along with weakness of the limbs leading to

paralysis, and eventually delirium. The victim usually dies through not

being able to breathe. It's almost worse if the sufferer survives, since

the body gets rid of the thallium slowly, meaning days or weeks of

agony. If the dose is repeated, it has the effect of being an

accumulative poison which kills gradually over a week or two. All things

considered, it's a long, slow method of murdering someone, of which any

sadist would be proud.

Graham Young may not have been a sadist in the conventional sense, but

he did take great pleasure in following and noting down every last

gruesome symptom each of his victims suffered, recording them each day

in exercise books and plotting graphs to analyze their progress.

This almost fetishistic documentation proved his downfall. Once the

firm's MD had alerted police, it didn't take detectives long to work out

that the illnesses had started shortly after a certain individual had

joined the Bovingdon firm. A quick consultation from a couple of

forensic scientists revealed the symptoms of the victims were consistent

with thallium poisoning. They were also kind enough to finally inform

the firm's bosses that Graham Young was a convicted poisoner.

Police immediately searched Graham Young's room in nearby Hemel

Hempstead, where they were confronted with walls covered in pictures of

Hitler and other Nazi leaders, accompanied by drawings of emaciated

figures holding bottles marked "poison," clutching their throats as

their hair fell out. They also found bottles, phials and tubes lined

along the window sill, and under his bed lay the incriminating diary,

with a number of entries following the progress of his "patients."

The day was Saturday, November 21, 1971, and Young was visiting his

father Fred and Aunt Winnie in Sheerness, Kent, some eighty miles away.

It was 11:30 at night when police knocked on the door, and Fred Young

immediately knew what they wanted. He pointed the officers towards his

son, and Winnie asked her nephew "Graham, what have you done?" "I don't

know what they are talking about, Auntie," he replied. But as he was

being led out, Fred Young heard him ask the officers, "Which one are you

doing me for?" After they had left, Fred gathered together Graham's

birth certificate and every other document relating to his son, and tore

them to shreds.

A Picture of Evil

Once in custody, Young admitted to the poisonings under interrogation,

and even boasted of committing "the perfect murder" of his stepmother

back in 1962, knowing he could still deny everything in court. He

laughed mockingly when he was asked for a written statement admitting

his guilt.

Yet for all his grotesque arrogance, he soon told police "the charade is

over," and was clearly resigned to his fate. That didn't mean, however,

that he wouldn't have his day in court. He planned to wring every ounce

of notoriety from the case, in pursuit of his ambition to become the

most infamous poisoner of all time.

Graham Young's trial took place at St. Albans Crown Court in June 1972.

On the defense stand, he eloquently argued the toss with the prosecuting

counsel, relishing the ultimate intellectual challenge of escaping

justice.

"He was very proud of being the first person to use thallium in a

poisoning case in Britain," remembers Peter Goodman, Young's defense

lawyer, "For him the whole thing was one big chemistry experiment, and I

suppose the trial was an experiment in seeing if he could use his

knowledge to argue his way out of it.

"He was clearly a very intelligent fellow," says Susan Nowak, who was in

court to report on the trial for The Watford Observer. "but he also came

across as incredibly creepy. You didn't want to make eye contact with

him because he just had this unnerving aura about him."

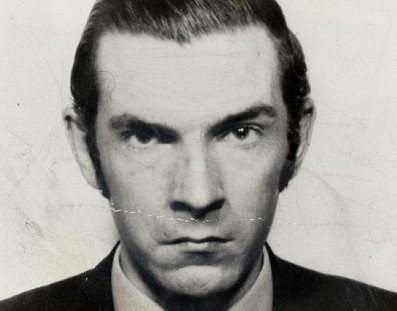

Young clearly enjoyed conveying such a chilling impression. When the

press asked for a picture of the defendant, he insisted they use one in

which he looked particularly cold-eyed and sinister. As it happened, the

glowering photograph actually came about by accident. Holden explains

that Young was scowling because he thought he had been cheated out of

some money by the coin-operated photo booth where the picture was taken.

It's hard to believe that Young seriously held out much hope of being

acquitted, but that doesn't account for the supreme arrogance of a man

who regarded himself as far more intelligent than virtually everyone he

encountered. While awaiting trial he wrote to his cousin Sandra

insisting "I stand a good chance of acquittal, for the prosecution case

has a number of inherent weaknesses. A strong point in my favor is that

I am NOT guilty of the charges."

Young's initial confidence was based on the assumption that the

prosecution wouldn't be able to prove beyond doubt that only he could

have administered the poisons. Since Bob Egle had been cremated, he

assumed proof of thallium poisoning would be impossible, while he had

made a point of offering Fred Biggs some thallium grains to help him

kill bugs in his garden, knowing he could later claim that Biggs had

misused them. As for the diary relating to the victims, he claimed they

were figments of his imagination on which he planned to base a novel.

Even a confession couldn't stand in his way. Despite having verbally

admitted his crimes to police on his initial arrest, he claimed in court

that he had simply told police what he thought they wanted to hear, in

order to be allowed food and clothing.

He reckoned without advances in forensic science that had been made

since 1962 when Molly Young's cremation meant her murder could not be

proved. Experts succeeded in finding traces of thallium in Bob Egle's

ashes, Fred Biggs" wife confirmed that he never used Young's thallium on

his garden, and as for that claim about the diary, once read out in

court, the diary entries sounded distinctly non-fictional. Excerpts

included the following:

"F (Fred) is now seriously ill. He has developed paralysis and

blindness. Even if the blindness is reverse, organic brain disease would

render him a husk. From my point of view his death would be a relief. It

would remove one more casualty from an already crowded field of battle."

On Diana Smart: "Di irritated me yesterday, so I packed her off home

with a dose of illness."

On an unidentified delivery driver: "In a way it seems a shame to

condemn such a likeable man to such a horrible end, but I have made my

decision."

Luckily for the driver concerned, there wasn't a delivery that week...

His entries also revealed a plan to murder David Tilson in his hospital

bed, after Young's initial doses had failed to finish him off. Young

intended to visit Tilson and offer him a swig from a hip flask of

brandy, which he knew Tilson would probably accept but also not tell the

nurses about, since drinking was against hospital rules. Needless to say

the patient would have found himself intoxicated in more lethal ways

than he expected. Tilson's relatively late admission to hospital, and

subsequent month off recuperating, apparently saved his life. He

eventually made a full recovery.

Adding all this evidence to the thallium and antimony found in Young's

room, and a phial in Young's jacket which he had intended to use as his

"exit dose" if he was caught, the prosecution had a strong case. Young

had taunted police that they could not convict him without demonstrating

a motive, but with such powerful evidence of murder, they didn't need to

show a clear motive.

Young was convicted of two murders, two attempted murders, and two

counts of administering poison. He was sentenced to four counts of life

imprisonment alongside two five-year sentences, and although he had told

warders he would break his own neck on the dock railings if convicted,

he failed to live up to his promise.

There was still a sensation in the courtroom, however, when Young's

background was revealed after the guilty verdict. There were gasps of

disbelief when it was announced that Young had done this kind of thing

before, and had been released from a secure mental institution mere

months previously.

"You looked at the jury," remembers Susan Nowak, "and the blood drained

from their faces when they heard about his previous convictions. The

verdict had not been a foregone conclusion, and they were probably

thinking "what if we'd let this maniac out onto the street?""

How Could They Let This Happen?

The jury at St. Albans crown court added a rider after Young was

sentenced, calling for an urgent official review of the UK laws covering

the sale of poisons. It was the least they could do considering the

circumstances of the case, and the British newspapers wasted no time in

expressing their outrage, alongside reports of the case's more salacious

details. How, they asked, could a convicted poisoner be freed from a

high security prison despite evidence of his continuing obsession with

poison and murder, and also still easily obtain poisons, and be

recommended for work within easy access of dangerous chemicals, without

his employers even being informed of his criminal record and the nature

of his convictions?

Within an hour of the verdict, the home secretary, Reginald Maudling,

announced that two separate inquiries had been set up into the control,

treatment and supervision of mentally ill prisoners. The inquiries led

to tightening of the laws on monitoring mentally ill offenders after

release.

It's easy to be wise in hindsight. The fact of the matter is that Graham

Young was a one-off, an exceptionally rare criminal whose crimes were

pretty much unprecedented, if not in terms of method, then certainly in

motive, since almost uniquely among poisoners, Young appeared to be

driven simply by misguided scientific obsession, married to a total

absence of empathy with the rest of humanity.

"I don't think he had any ill will towards the people he killed," says

Peter Goodman, "he just had no morals. The reason he poisoned those

closest to him was simply because he could closely observe the symptoms.

He was a deranged scientist essentially."

Winifred Young wrote that people who said "Imagine if he'd walked into a

crowded café!" missed the point about her brother's motivation.

"My answer was 'that would be no good to Graham"...cause in such

circumstances Graham would never be able to observe the effect of the

poison. The person or persons poisoned would simply get up from the

table and walk out, and Graham would never see them again - and that

would be no good to him...he wanted to study the effects; to watch how

poison worked, as though he were merely carrying out a clinical

experiment."

Still, at least some people were served food and drink by Young and

survived without any ill effects. Goodman remembers one occasion when he

went to see his charge in prison. "He offered me a piece of cake. I

hesitated, and he said "Come on, I wouldn't poison my lawyer." That's

pretty much what he said to some of his victims, but I ate it anyway..."

A brave man.

Epilogue

Graham Young served his sentence in the maximum security Parkhurst

prison on the Isle of Wight, where he died in 1990, aged 42. The

official diagnosis was a heart attack, but many have their doubts. In

'the Young Poisoner's Handbook," the movie made about the story in 1995,

it's suggested he killed himself by typically ingenious poisonous means.

Others suspect fellow Parkhurst inmates.

"I wonder if he tried to do the same poisoning tricks he pulled off in

Broadmoor," offers Peter Goodman, "only someone took offence this time."

Anthony Holden, author of the book "The St. Albans' Poisoner," backs up

that theory, asking "Who in his right mind...would want to spend an

indefinite period incarcerated with a man who could extract poison from

a stone - or in this case, perhaps, iron bars - in order to kill some

time by doing just that to his everyday companions?"

Whatever the cause of his death, Young would appear to have achieved a

degree of the immortality he craved. He would often ask people if they

thought he would ever have the honor of having a waxwork made of him and

installed in the "Chamber of Horrors" in London's Madam Tussaud's

museum. He dreamed of taking his place in there alongside one of his

heroes, Dr. Crippen. His wish was finally granted a few years later.

Parkhurst prison is reserved for Britain's most dangerous prisoners,

usually those with mental problems. But in legal terms Young was of sane

mind when he committed his crimes. He was bad rather than mad.

'There was obviously something not right in his head," concludes

Goodman. "I felt sorry for the guy."

By all accounts, that's considerably more than Graham Young ever felt

for anyone.

When asked if he felt remorse, he replied, "No, that would be

hypocritical. What I feel is in the emptiness of my soul."

Winifred Young remembers telling him he should get out more, and try and

make more friends.

"No," he said, "Nothing like that can help. You see, there's a terrible

coldness inside me."

Ian Brady and Graham Young - A Meeting of Minds

Due to the notoriety of his case, Graham Young lived in constant fear of

being poisoned by fellow inmates while in Parkhurst. But one person in

whose company he felt relatively safe was the Moors Murderer Ian Brady.

In 2001, Brady won a long battle for the right to publish a book 'the

Gates Of Janus," in which he offers his insider's view on a number of

serial killer cases. One of those chosen for this rare accolade was his

old friend Graham Young.

"He sometimes grew a Hitler moustache," remembers Brady, "fastidiously

trimming it with a razor until the skin around it was red raw and the

prison staff had to stop him."

He tells of playing Chess with Young on a daily basis, with Young

favoring the black pieces, "likening their potency to the Nazi SS."

Brady claims he always beat him.

The pair bonded over their shared fascination with Nazi Germany.

The bisexual Brady even sounds positively amorous when he describes how

Young shared the "boyish good looks" of a mutual idol, Dr. Josef Mengele.

However, he also reports that Young was "genuinely asexual," and

suggests that this was another example of him exercising power over 'the

herd." "Power and death were his aphrodisiacs," he asserts.

Brady suggests Young was, like him, something of a Nietzschian in

outlook, obsessed with proving himself superior to 'the common herd."

Am I a unique individual or simply a common insect? Do I possess the

courage to act autonomously, against man and god?

The serial killer unfortunately perceives that the only real way to

distance himself from the banality and senility of the herd is to

exercise free will of the most extreme kind – by killing others.

Of Young's flamboyant performance in court he writes:

He probably likened himself to Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, routing

the allied prosecutors and dominating the proceedings at the Nuremberg

trials.

Or could that simply be Brady's warped and rather ludicrous fantasy?

He viewed his destiny in Wagnerian terms and would sit in his miserable,

almost bare cell as though it were the Berlin Bunker, listening

rapturously to Gotterdammerung, a doomed figure with his grandiose

dreams in ruins. When depressed...he had the dejected stoop of Hitler in

his final days.

Bear in mind while reading this that Brady would probably find parallels

with Hitler and Nazi Germany in an episode of The Waltons.

The Moors Murderer reports that the only music Young liked were Jeff

Wayne's "War Of The Worlds" and "Hit The Road Jack" by Ray Charles, and

he would amuse himself by reading obituaries of the great and the good

in The Times of a morning. He also fantasizes that Young killed himself.

Possibly he commended 'the poisoned chalice" to his own lips, in a final

gesture of triumphant contempt.

Or could it have been a final gesture of wanting to kill himself?

He concludes the chapter by pointing out that Graham's "relatively

modest use of thallium" was nothing compared to its usage during the

first gulf war, in which American forces bombarded the enemy with

thallium-tipped shells.

Had Graham lived to see it, this would have brought a cynical smile to

his thin pale lips, and a mischievous sparkle to his dark eyes.

Finally, Brady concludes, in all seriousness, "It was difficult not to

empathies with Graham Young."

Okay, time for your medication, Mister Brady.

CrimeLibrary.com