He then

ordered the manager's wife, Hye Kyong Kim, to retrieve her dying

husband's wallet and car keys from his pants pocket and ordered

her to empty the cash register. He then ordered her into her

vehicle and fled with her.

Watts sexually assaulted Mrs. Kim in

her car, then took her to his mother-in-law's apartment, where he

again raped and sodomized her and allowed his roommate, Terrance

Bolden, to rape her. Watts also forced Mrs. Kim to ingest

narcotics and attempted to insert his pistol into her vagina. Mrs.

Kim survived the ordeal and testified against Watts at his trial.

Watts was captured about three hours after the shootings, after he

attempted to flee by ramming two police cars. At the time of his

arrest he was still carrying the Tec-22 pistol which was matched

to slugs removed from the victims. Upon arrest, Watts gave a

complete confession, admitting the murders. Bolden was convicted

of aggravated sexual assault and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Holding Mrs. Kim at gunpoint, Watts ordered her

into the Kims’ vehicle and fled the scene with her. For several

hours, Watts sadistically tortured and sexually assaulted Mrs. Kim

both in the vehicle and later in his mother-in-law’s apartment –

at one point allowing his roommate to rape her. Watts himself

repeatedly sodomized Mrs. Kim, forced her to ingest narcotics, and

attempted to rape her with the Tec-22 pistol. Acting on a phoned

in tip from a neighbor who had seen a TV story about the murders

and the missing vehicle, San Antonio Police captured Watts only

after he unsuccessfully attempted to escape by ramming the Kims’

vehicle into two police cruisers.

Kim's wife survived and testified against Watts

at his capital murder trial in 2003, identifying him as the gunman

and her attacker. At his trial, defense lawyers didn't deny Watts

was responsible for the slayings but tried to show he didn't

intend to kill the victims and was high on drugs.

In his written confession, Watts told police he

shot the three because they were yelling at him. "I did what I had

to do," he wrote. "I needed fast money, because that's what I'm

used to." When the execution date was set, Watts was removed from

the courtroom twice because of epithet laced tirades to the judge.

Watts v. Quarterman, 448 F.Supp.2d

786 (W.D.Tex. 2006) (Habeas).

Background: Petitioner sought writ of habeas

corpus, challenging his capital murder conviction and death

sentence.

Holdings: The District Court, Orlando F. Garcia,

J., held that:

(1) petitioner procedurally defaulted on

federal habeas claims asserting violation of Eighth Amendment

right to present mitigating evidence at penalty phase;

(2) petitioner procedurally defaulted on federal habeas claim

asserting violation of First Amendment right to freedom of

association; and

(3) prosecutor's closing argument at penalty phase did not make

the trial fundamentally unfair. Petition denied.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

ORLANDO L. GARCIA, District Judge.

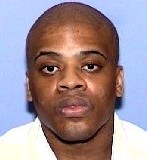

Petitioner Kevin Michael Watts, also known as

Kevin Vann, filed this federal habeas corpus action pursuant to

Title 28 U.S.C. Section 2254 challenging his February, 2003, Bexar

County capital murder conviction and sentence of death. For the

reasons set forth below, petitioner is entitled to neither federal

habeas corpus relief nor a Certificate of Appealability from this

Court.

I. Statement of the Case

A. Petitioner's Offense

The essential facts surrounding petitioner's

capital offense have never been in dispute. Petitioner executed a

pair of detailed, written statements shortly after his arrest and

has never presented any state or federal court with any evidence

controverting same.FN1

FN1. Two versions of petitioner's original,

written, post-arrest, statement or confession were admitted into

evidence and read verbatim into the record during the guilt-innocence

phase of petitioner's capital murder trial. A redacted or edited

version was admitted as State Exhibit No. 2 and recounted

petitioner's robbery of the Sam Won Gardens restaurant, his fatal

shooting of three persons inside the restaurant, his kidnaping of

a fourth person from the restaurant, and the circumstances

surrounding petitioner's arrest several hours later. Statement of

Facts from petitioner's trial (henceforth “S.F. Trial”), Volume 18

of 26, testimony of Barney Whitson, at pp. 63-68. A copy of State

Exhibit No. 2 appears in S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26.The full,

unedited, version of petitioner's original statement was admitted

into evidence as State Exhibit No. 2-A and read into the record

during the punishment phase of petitioner's trial. S.F. Trial,

Volume 22 of 26, testimony of Barney Whitson, at pp. 18-19. A copy

of State Exhibit No. 2-A appears in S.F. Trial, Volume 25 of 26.

In addition, petitioner gave law enforcement

officers a second written statement shortly after he executed his

first statement. This second statement was admitted and read

verbatim into evidence during the punishment phase of petitioner's

capital trial as State Exhibit No. 101. S.F. Trial, Volume 22 of

26, testimony of Barney Whitson, at pp. 22-27. A copy of State

Exhibit No. 101 appears in S.F. Trial, Volume 26 of 26.

Furthermore, the surviving victim and

eyewitness to petitioner's armed robbery and fatal shooting of

three people testified at petitioner's trial in a manner wholly

consistent with petitioner's written confessions.

More specifically, Hye Kyong Kim, the widow of Sam Won Gardens

restaurant manager Hak Po Kim, testified without contradiction at

the guilt-innocence phase of petitioner's capital trial that, on

the morning of March 1, 2002, (1) petitioner entered the

restaurant, fired a shot, and directed her and her husband at

gunpoint to move to the kitchen area, (2) petitioner then directed

the Kims and two restaurant employees, Yuan Tzu “Tina” Banks and

Chae Sun “Gina” Shook, to face a wall and kneel, (3) Mrs. Kim then

heard three shots, turned, and saw three bodies on the floor, (4)

petitioner then forced her to follow him, open the cash register,

and give petitioner all the money in the register, (5) petitioner

directed Mrs. Kim to retrieve the keys to her husband's vehicle

from his pocket, (6) when petitioner demanded more money, Mrs. Kim

also retrieved her husband's wallet as well as his keys and gave

same to petitioner, and (7) petitioner forced her into her

husband's vehicle and fled the scene in their vehicle.FN2

FN2. S.F. Trial, Volume 20 of 26, testimony of

Hye Kyong Kim, at pp. 132-41, 186-89, 191-95, 197, 220-22. Mrs.

Kim also testified petitioner threatened her during their flight

from the restaurant, struck her in the face with his fist, and

fired the gun inside the vehicle. Id., at pp. 195, 202-03, 208-09.

A produce delivery truck driver testified at

petitioner's trial that, on the morning in question (1) he

observed a black male shove a female into the Kims' vehicle and

flee the scene and (2) he entered the unusually silent restaurant

and observed two bodies on the floor. FN3. S.F. Trial, Volume 18

of 26, testimony of Jesse Rios, at pp. 77-114.

Several San Antonio Police Officers testified

regarding the circumstances surrounding petitioner's arrest on the

afternoon of March 1, 2002, specifically about (1) the

petitioner's unsuccessful attempt to flee from police by smashing

the Kims' stolen vehicle into two police vehicles before

petitioner drove into a wall, rendering the Kims' vehicle

inoperable, (2) Mrs. Kim's distraught condition as she fled the

damaged stolen vehicle, and (3) the handgun and cash police found

inside petitioner's jacket once petitioner had been arrested. FN4

FN4. Several San Antonio Police officers

testified (1) petitioner drove the Kims' stolen vehicle at a rapid

rate of speed toward the exit of an apartment complex in North San

Antonio, (2) the petitioner appeared wide-eyed when he saw police

officers in full uniform, (3) petitioner drove the Kims' stolen

vehicle, a silver Toyota 4Runner, into the side of a uniformed

officer's unmarked vehicle, hopped a curb, struck a second, marked,

police cruiser, and then slammed into the wall of an apartment

building, at which point the Kims' vehicle was no longer operable,

(4) a search of petitioner produced a TEC-22 handgun tied to the

petitioner's neck and shoulder inside the petitioner's jacket, as

well as several rolls of cash, and (5) Mrs. Kim appeared to be

distraught as she fled the damaged vehicle. S.F. trial, Volume 19

of 26, testimony of Andy Hernandez, at pp. 41-60; testimony of

David Payne, at pp. 85-98; testimony of Robert Rosales, at pp.

138-51; Volume 20 of 26, testimony of James Holguin, at pp.

27-41.A latent fingerprint examiner also testified fingerprints

found inside the Kims' stolen 4Runner matched petitioner's. S.F.

trial, Volume 20 of 26, testimony of Ray Frausto, at pp. 116-22.

Autopsies revealed that each of the three

persons shot inside the restaurant died as a result of a single

gunshot wound to the back of the head.FN5

FN5. The medical examiner who conducted the

autopsies of the three victims testified without contradiction

during the guilt-innocence phase of petitioner's trial that (1)

each of the three victims died as a result of a single gunshot

wound to the back of the head, (2) in each case, the fatal bullet

wound tracked from back to front and downward through the skull

and brain, with the bullet coming to rest inside the base of the

skull, and (3) all three fatal gunshot wounds were consistent with

a shot having been fired from above and behind the victim's head.

S.F. Trial, Volume 19 of 26, testimony of Randall Frost, at pp.

13-26.

Ballistics tests established the handgun

petitioner was carrying at the time of his arrest fired each of

the fatal shots.FN6

FN6. A firearms examiner testified (1) that

four cartridge casings found inside the restaurant were all fired

by the same handgun police found tied around petitioner's neck and

shoulder at the time of his arrest and (2) the three bullets

removed during the autopsies of the three victims were all fired

by the same weapon, i.e., the one petitioner had tied to his neck

and shoulder at the time of his arrest. S.F. Trial, Volume 20 of

26, testimony of Edard William Love, Jr., at pp. 84-94.

B. Indictment

On May 21, 2002, a Bexar County grand jury

returned a one-Count indictment in cause no. 2002-CR-3470 charging

petitioner with having fatally shot Hak Po Kim (1) while in the

course of the same criminal transaction in which petitioner

fatally shot Yuan Tzu Banks and (2) while in the course of

committing and attempting to commit the robbery of Hak Po Kim,

Yuan Tzu Banks, Chae Sun Shook, and Hye Hyong Kim.FN7

FN7. Transcript of pleadings, motions, and

other documents filed in petitioner's state trial court proceeding

(henceforth “Trial Transcript”), Volume 1 of 2, at p. 141.

C. Guilt-Innocence Phase of Trial

The guilt-innocence phase of petitioner's trial

began on February 10, 2003. On February 13, 2003, after hearing

the evidence summarized above and deliberating less than three

hours, the jury returned its verdict, finding petitioner guilty of

capital murder.FN8

FN8. Petitioner's jury began its deliberations

at the guilt-innocence phase of trial not earlier than 1:40 p.m.

on February 13, 2003 and returned its guilty verdict not later

than 4:10 p.m. the same date. S.F. Trial, Volume 21 of 26, at p.

128; Trial Transcript, at pp. 75-89.

D. Punishment Phase of Trial

The punishment phase of petitioner's trial

commenced on February 14, 2003.

1. The Prosecution's Case

During the punishment phase of petitioner's

trial, the prosecution presented (1) a host of documentary

evidence and testimony from law enforcement officers regarding

numerous instances of criminal conduct by petitioner FN9 and (2)

testimony from correctional officers concerning numerous instances

of violent or disruptive conduct by petitioner while in detention

awaiting trial for capital murder.FN10

FN9. More specifically, a fingerprint examiner

testified petitioner's fingerprints matched those found on not

less than eleven judgments of conviction in various misdemeanor

criminal proceedings, including the offenses of evading arrest,

criminal mischief, possession of marijuana, failure to identify (two

counts), criminal trespass (three counts), driving while

intoxicated, resisting arrest, and assault causing bodily injury (two

counts). S.F. Trial, Volume 22 of 26, testimony of Richard

Contreras, at pp. 10-16.A juvenile probation officer testified

petitioner had received a probated sentence in 1997 for unlawfully

carrying a weapon. S.F. trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of Eddie

Ortiz, at pp. 7-9.

A San Antonio Police officer testified about an

incident on July 21, 2001 in which (1) he responded to a call from

a woman named Marquketa Rector, whose face was lacerated and

covered in blood and who identified petitioner as the person who

had beaten her in the face, (2) he arrested petitioner, (3)

thereafter, while emergency medical personnel treated Ms. rector's

injuries, Tiffany Prince, who identified herself as petitioner's

common law wife, approached him and informed him that petitioner

had also assaulted her by striking her repeatedly in the face.

S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of Montrose Butler, at pp.

124-29.

Another San Antonio Police officer testified

about an incident on February 8, 2002 during which petitioner

identified himself as a member of a street gang. S.F. Trial,

Volume 23 of 26, testimony of Ricardo Vijil, at pp. 133-34.

Yet another San Antonio Police officer

testified about an incident on December 15, 1998 during which

petitioner violently resisted arrest, fought with the officer, and

caused the officer to sustain a severely lacerated leg which

required several sutures to close. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26,

testimony of Randy Geary, at pp. 101-23.

FN10. More specifically, several correctional

officer at the Bexar County Adult Detention Center testified

concerning incidents (1) on March 6, 2002, during which petitioner

exchanged punches with an Hispanic inmate, (2) on July 1, 2002,

during which petitioner became argumentative, assumed a physically

threatening, combative, posture, verbally abused, and threatened a

guard, (3) on October 13, 2002, during which petitioner had a

physical altercation with an Hispanic inmate in the rec yard which

necessitated both inmates being sent to the infirmary, and (4) on

November 14, 2002, during which petitioner and another Black

inmate were involved in a fight with two Hispanic inmates. S.F.

Trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of Carlos Soto, at pp. 30-34;

testimony of Jack Farmer, at pp. 64-69; testimony of William

Wadsworth, at pp. 55-58; testimony of Christopher LeBlanc, at pp.

46-49.

The prosecution also introduced a letter

petitioner had written while in custody awaiting trial for capital

murder, in which petitioner made several ethnic slurs against

Hispanics and Anglos and indicated his desire to join a Black

prison gang.FN11

FN11. The letter in question was admitted into

evidence during the punishment phase of petitioner's trial as

State Exhibit No. 105-A. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of

Mark Wells, at pp. 79-81 & 95. A copy of State Exhibit No. 105-A

appears in S.F. Trial, Volume 26 of 26.Significantly, the only

objection petitioner's raised to the admission of this letter

consisted of an argument that BCADC officials had illegally seized

the letter. At no point did petitioner's trial counsel raise any

complaint that admission of the letter violated petitioner's First

Amendment rights. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26, at pp. 82-95.

Petitioner's kidnap victim, Hye Kyong Kim,

returned to the stand at the punishment phase of petitioner's

capital trial and testified that, after petitioner fled the

restaurant with her in her husband's vehicle, petitioner (1) tied

her hands to a headrest, (2) drove around for several hours, (3)

forced her to remove her shoes and pants, (4) repeatedly sprinkled

cocaine on his penis and forced her to perform fellatio on him,

(5) threatened to insert the barrel of his gun inside her vagina,

(6) snorted cocaine with a rolled-up ten or twenty dollar bill,

(7) unsuccessfully attempted to have sex with her on several

occasions, (8) sprinkled cocaine on her vagina and licked it off,

(9) gave her a beer to drink, (10) blindfolded her and took her to

an apartment complex where he locked her in a closet, directed her

to remove her underwear, and later directed her to put on a dirty

pair of underwear, (11) removed her from the closet and again

directed her to fellate him multiple times, (12) after again

unsuccessfully attempting to sexually assault her, took a shower,

and gave another occupant of the apartment permission to rape her,

(13) made her count the money he had taken from the restaurant,

and (14) again blindfolded her before returning her to the stolen

vehicle just before police apprehended him. FN12. S.F. Trial,

Volume 22 of 26, testimony of Hye Kyong Kim, at pp. 51-60.

2. The Defense's Case

The defense introduced testimony from

petitioner's cousins and mother-in-law to the effect that (1)

petitioner had developed a drug problem while living with his

mother in California and, at age fourteen, moved to live with an

aunt in San Antonio, (2) petitioner was a loving, friendly, giving,

kind-hearted person, (3) the handgun which petitioner told police

officer was his really belonged to one of his cousins, (4) another

of petitioner's cousins was actually the person who had assaulted

Marquketa Rector, not petitioner, (4) his conduct on March 1, 2002

was aberrational, (5) the night before the murders, petitioner

consumed massive quantities of alcohol and cocaine, and multiple

pills of Ecstasy, Valium, and Xanax, and (6) petitioner was a good

father to his daughter.FN13

FN13. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of

Sonia Watts, at pp. 170-225; testimony of Ronald Melvin Watts, at

pp. 226-47; testimony of Alicia Prince, at pp. 247-54.

Petitioner's common law wife testified on

direct examination that (1) she had known petitioner for two years

and seven months, (2) she had only known petitioner to use drugs

during the two months immediately prior to petitioner's capital

offense, (3) when petitioner was high on drugs he was a very

different person than he was otherwise, (4) she spoke with

petitioner on the phone the night before the murders and could

tell petitioner was high on something, and (5) while petitioner

once pushed her in the face, petitioner was normally a nice,

loving, person.FN14 On cross-examination, however, she admitted

(1) petitioner had a drug problem at least as early as July, 2001,

(2) petitioner failed to take advantage of the drug-treatment

programs available to him while he was in custody prior to March,

2002, and (3) petitioner had been in a street gang in California

before he came to live in Texas.FN15

FN14. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, testimony of

Tiffany Prince, at pp. 73-86. FN15. Id., at pp. 91-103.

The defense then introduced the testimony of a

licensed social worker and chemical dependency counselor who

described herself as a “mitigation specialist” and who testified

she had interviewed petitioner and his family and reviewed

petitioner's school, jail, medical, and psychiatric records and

opined that (1) petitioner had experienced many negative

influences during his developmental years and (2) petitioner was

probably in the midst of a substance-induced psychosis or

delusional state at the time of his capital offense.FN16

Significantly, the state trial court repeatedly sustained the

prosecution's hearsay objections whenever defense counsel

attempted to elicit testimony from this witness concerning the

contents of petitioner's school, medical, or jail records and

concerning the contents of her discussions with petitioner's

family and friends.FN17

FN16. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, testimony of

Linda Mockeridge, at pp. 113-32. FN17. Id., at pp. 122-23, 128-29,

132.

3. The Verdict

After deliberating less than three hours, the

jury returned its verdict at the punishment phase of petitioner's

capital trial, unanimously finding (1) there was a probability the

petitioner would commit criminal acts of violence that would

constitute a continuing threat to society and (2) taking into

consideration all the evidence, including the circumstances of the

offense and the defendant's character, background, and personal

moral culpability, there were insufficient mitigating

circumstances to warrant that a sentence of life imprisonment,

rather than a death sentence, be imposed on petitioner.FN18

FN18. Petitioner's jury retired to deliberate

at the punishment phase of petitioner's trial at 3:35 p.m. on

February 19, 2003 and returned its verdict at approximately 5:50

p.m. that same date. Trial Transcript, Volume 1 of 2, at pp.

102-03; S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, at pp. 198-206.

E. Direct Appeal

In an unpublished, per curiam opinion issued

December 15, 2004, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed

petitioner's conviction and sentence on direct appeal.FN19

Petitioner did not thereafter seek certiorari review of his

conviction and sentence by the United States Supreme Court.

FN19. Watts v. State, AP-74,593 (Tex.Crim.App.

December 15, 2004).As points of error on direct appeal, petitioner

argued (1) the state trial court abused its discretion when it (a)

admitted evidence during the punishment phase of petitioner's

trial indicating petitioner's desire to join a black racist prison

gang and (b) permitted the prosecution to make a racist jury

argument referring to same, (2) petitioner's sentence was grossly

disproportionate to petitioner's crimes, and (3) the death

sentence violates the Eighth Amendment. The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals held (1) petitioner failed to properly preserve

his complaints about the admission of petitioner's letter

indicating petitioner's desire for membership in a black prison

gang and the prosecution's closing argument referring to same by

failing to timely object to same on constitutional grounds, i.e.,

the grounds urged on appeal, (2) there is no right to a

proportionality review of a capital sentence, and (3) petitioner's

conclusory Eighth Amendment claim was without merit.

F. State Habeas Corpus Proceeding

Petitioner filed his first state habeas corpus

application on May 3, 2004, asserting three claims for relief

therein.FN20 On October 14, 2004, the state responded to

petitioner's first state habeas corpus application. FN21 On

October 25, 2004 petitioner filed a “supplemental” state habeas

corpus application in which, for the first time, he asserted

claims that his trial and appellate counsel had rendered

ineffective assistance by failing to timely object to, and present

points of error on direct appeal complaining about, the state

trial court's rulings on the admissibility of Ms. Mockeridge's

expert testimony.FN22

FN20. Transcript of pleadings, motions, and

other documents filed in petitioner's first state habeas corpus

action, i.e., App. No. 62-250-01 & 62,650-02 (henceforth “State

Habeas Transcript”), at pp. 1-34.Petitioner's first state habeas

corpus application asserted three claims for relief, to wit,

arguments that (1) the state trial court erred when it “severely

limited” the testimony of petitioner's mitigation expert, (2) the

state trial court erred when it permitted the prosecution to

introduce evidence showing petitioner's desire to join a black

racist prison gang, and (3) the prosecution improperly used its

evidence of petitioner's desire to join a black prison gang in a

racist manner during closing argument.

FN21. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 79-99.The

state argued that (1) the state trial court had not, in fact,

restricted Ms. Mockeridge's expert testimony but, rather, had

permitted her to express the same opinions before the jury that

she expressed during the hearing on the admissibility of her

testimony and petitioner's trial counsel failed to preserve any

error concerning the trial court's rulings on Ms. Mockeridge's

status as an expert witness by failing to make a timely proffer of

any additional testimony she could have given at petitioner's

trial and failing to challenge the trial court's ruling on direct

appeal, (2) petitioner's trial counsel likewise failed to preserve

any alleged constitutional error in the admission of petitioner's

vitriolic letter from prison or to the prosecution's closing jury

argument at the punishment phase of petitioner's trial by failing

to make a timely objection on constitutional grounds to same, and

(3) petitioner's grounds for state habeas relief, at best, raised

only harmless error. FN22. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 35-46.

In an Order issued November 23, 2004, the state

habeas trial court (1) found the trial court had ruled that Ms.

Mockeridge, while not specifically determined to be an expert on

mitigation, would be permitted to testify as an expert, (2) found

the trial court sustained the prosecution's hearsay objection to

Ms. Mockeridge's summary chart, (3) found Ms. Mockeridge was

permitted to testify regarding the nature of the documents and

other evidence she had reviewed while developing her psycho-social

history of petitioner but was not allowed to testify as to the

specific contents of those hearsay documents and conversations,

(4) found Ms. Mockeridge was permitted to express her opinions

that numerous negative factors impacted on petitioner's childhood

development and that petitioner was probably “in the midst of a

substance [-]induced psychosis” at the time of his offense, (5)

found any confusion in the trial court's rulings regarding Ms.

Mockeridge's testimony excluded only hearsay testimony on her part

and not any expression of her expert opinions, (6) found

petitioner never complained to the trial court that its rulings

had impacted on petitioner's constitutional right to present

mitigating evidence, (7) concluded petitioner had procedurally

defaulted on his constitutional complaint regarding the trial

court's rulings on Ms. Mockeridge's testimony by failing to timely

make a bill of exceptions regarding same and failing to present

those complaints on direct appeal, (8) alternatively concluded

there was no error in the trial court's rulings on the proper

scope of Ms. Mockeridge's testimony, (9) found petitioner's trial

counsel first raised the issue of gang membership at trial, (10)

found no evidence was admitted identifying either the Longview

Crips, i.e., the California street gang to which petitioner

admitted once having been a member, or the Black Gorilla Family,

i.e., the prison gang to which petitioner wrote he planned to seek

membership, were “racist” gangs, (11) found petitioner made no

constitutional objection to the admission of any evidence showing

petitioner was either a member of the Longview Crips or hoped one

day to be a member of the Black Gorilla Family, (12) found

petitioner made no constitutional objection to the prosecution's

wholly proper summary of the evidence before the jury during

closing argument at the punishment phase of petitioner's trial,

and (13) concluded petitioner procedurally defaulted on his

constitutional complaints about the admission of State Exhibit No.

105-A and the prosecution's closing argument by failing to make

timely objections on constitutional grounds thereto. FN23. State

Habeas Transcript, at pp. 180-204.

In an Order issued July 11, 2005, the state

habeas trial court ruled petitioner's “supplemental” application

was untimely and did not qualify under applicable state law as a

“successive” application. FN24. State Habeas Transcript, at pp.

169-71.

In an unpublished, per curiam, Order issued

October 19, 2005, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (1) adopted

the trial court's findings and conclusions concerning petitioner's

initial three claims, (2) denied all relief requested in

petitioner's initial state habeas corpus application, and (3)

dismissed petitioner's “supplemental” state habeas application as

a successive application under the Texas writ-abuse statute. FN25.

Ex parte Kevin Watts, WR-62,650-01 & WR-62,650-02 (Tex.Crim.App.

October 19, 2005).

G. Petitioner's Federal Habeas Corpus

Proceeding

Petitioner filed his federal habeas corpus

petition on December 29, 2005, alleging in his petition (1) the

state trial court violated his Eighth Amendment right to present

mitigating evidence when it restricted the trial testimony of its

mitigation expert, Ms. Mockeridge, by not permitting her to

testify “as a mitigation expert,” (2) the trial court violated

petitioner's First Amendment rights and the Supreme Court's

holding in Dawson v. Delaware by permitting the prosecution to

admit evidence showing petitioner's desire for membership in a

black prison gang, and (3) the prosecution violated petitioner's

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment rights when it used evidence of

petitioner's gang affiliation “in a racist manner' during closing

arguments at the punishment phase of trial”. FN26. Petitioner's

Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, filed December 29, 2005,

Docket entry no. 6 (henceforth “Petition”).

On May 18, 2006, respondent filed his answer,

arguing in pertinent part that (1) petitioner had procedurally

defaulted on his complaints regarding the trial court's rulings on

the admissibility of Ms. Mockeridge's testimony by failing to

contemporaneously object thereto, timely make a bill of exceptions,

or raise same on direct appeal, (2) the state trial court

committed no constitutional error in its rulings regarding Ms.

Mockeridge's testimony or the admissibility of the hearsay

contained in her report and summary chart, (3) petitioner

procedurally defaulted on his constitutional complaints regarding

the admission of petitioner's letter regarding his hoped-for

prison gang membership by failing to make a contemporaneous

constitutional objection thereto, (4) the trial court committed no

constitutional error when it admitted petitioner's letter, (5)

petitioner procedurally defaulted on his constitutional complaints

concerning the prosecution's punishment-phase closing argument by

failing to raise any timely objection thereto, and (6) any error

in the state trial court's failure to sua sponte correct the

prosecution during closing argument did not rise above harmless

error. FN27. Docket entry no. 12.

On June 13, 2006, petitioner filed a reply to

respondent's answer in which petitioner argued (1) respondent's

arguments effectively eliminated the need for petitioner to allege

and prove ineffective assistance by petitioner's trial counsel,

(2) the state trial court effectively prevented petitioner from

presenting mitigating evidence showing the details of petitioner's

neglected and deprived childhood, and (3) the “illiterate

gibberish” contained in petitioner's letter from jail was

erroneously construed by the prosecution during closing argument

as threatening in nature. FN28. Docket entry no. 16.

* * *

III. Exclusion of Mitigating Evidence Claim

A. The Claim

In his first claim herein, petitioner argues

the state trial court violated his Eighth Amendment right to

present mitigating evidence when it restricted the trial testimony

of its mitigation expert, Ms. Mockeridge, by not permitting her to

testify “as a mitigation expert” about numerous events which

negatively impacted petitioner's childhood development, including

the fact the petitioner (1) was sexually abused by a male baby-sitter,

(2) engaged in gang activities and drug use from an early age, and

(3) experienced a very disruptive family life. FN29. Petition,

docket entry no. 6, at pp. 8-17.

More specifically, petitioner argues that, but

for the trial court's rulings, Ms. Mockeridge could have testified

that, in her opinion, (1) petitioner's health and emotional

development were at risk from his early youth, (2) petitioner felt

abandoned and lacked a sense of trust, (3) as a child, petitioner

was preoccupied and oriented to a survival mode, (4) persons

raised in survival mode lack good coping skills, (5) as a result

of having been victimized by a sexual predator, petitioner

developed trust and abandonment issues and a need to belong and to

have safety, which, in turn led to petitioner becoming involved

with gangs by age eight, (6) petitioner began abusing drugs at age

ten, (7) petitioner had genetic loading with a positive family

history of drugs and alcohol, (8) petitioner developed insecure,

isolated, unhealthy relationships, (9) petitioner was failure-oriented,

possessed low self-concept, and felt hopeless, (10) petitioner

learned inappropriate responses, behaviors, and beliefs, (11)

petitioner's life view was one of hopelessness, lack of coping

skills, poor judgment, and impaired decision-making ability, (12)

petitioner had a distorted sense of reality and identity, low

tolerance, no sense of direction or purpose, and inappropriate

responses, (13) petitioner is emotionally damaged, disabled, and

dysfunctional, uses illegal drugs to self-medicate to calm himself,

and (14) petitioner was probably in a psychotic state at the time

of the murders. FN30. Affidavit of Linda Mockeridge, attached as

Exhibit L to Petition, docket entry no. 6. Petitioner presented

the same affidavit to the state courts during his state habeas

corpus proceeding. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 30-32.

B. State Court Disposition

During the punishment phase of petitioner's

capital trial, the trial court held a hearing outside the presence

of the jury during which Ms. Mockeridge testified concerning (1)

her training and experience as a master's level social worker,

licensed chemical dependency counselor, psychotherapist, and

“mitigation specialist,” (2) the extent of her efforts to

investigate petitioner's background and to develop a psycho-social

history of petitioner, (3) her opinion that petitioner was

probably in a psychotic state at the time of his capital

offense.FN31

After hearing extensive argument from the

parties regarding whether “mitigation science” was a legitimate

field of scientific inquiry for which Ms. Mockeridge qualified as

an “expert,” the state trial judge (1) ruled “in an abundance of

caution” that he would permit Ms. Mockeridge to testify as an

expert but was not specifically finding her to be an expert as to

“mitigation science” per se, (2) ruled inadmissible a summary

chart prepared by Ms. Mockeridge which contained hearsay, and (3)

advised the parties he would address the prosecution's concerns

about Ms. Mockeridge's apparent plans to relate to the jury wholly

hearsay information she had obtained from other sources on a

question-by-question basis.FN32

FN31. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, testimony of

Linda Mockeridge, at pp. 5-56. FN32. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26,

at pp. 57-72.

Thereafter, petitioner called Ms. Mockeridge as

a witness and she testified she had interviewed petitioner and his

family and reviewed petitioner's school, jail, medical, and

psychiatric records and opined that (1) petitioner had experienced

many negative influences during his developmental years and (2)

petitioner was probably in the midst of a substance-induced

psychosis or delusional state at the time of his capital

offense.FN33 The state trial court repeatedly sustained the

prosecution's hearsay objections whenever defense counsel

attempted to elicit testimony from Ms. Mockeridge concerning the

contents of petitioner's school, medical, or jail records and

concerning the contents of her discussions with petitioner's

family and friends. FN34

On cross-examination, Ms. Mockeridge admitted

(1) she was unaware of the legal definition of “mitigating

evidence” until the date of petitioner's trial, (2) a “mitigation

specialist” does basically the same thing as a social worker,

i.e., investigate a person's background for the purpose of

developing a psycho-social history of that person, and (3) she had

not reviewed any of the police reports or other evidence relating

to petitioner's capital offense. FN35

FN33. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, testimony of

Linda Mockeridge, at pp. 113-32. FN34. Id., at pp. 122-23, 128-29,

132. FN35. Id., at pp. 134-51.

Petitioner's trial counsel made no effort

whatsoever to elicit any opinion testimony from Ms. Mockeridge

along the lines of that contained in the affidavit petitioner

later presented to the state habeas court and to this Court, i.e.,

addressing her opinions concerning the impact of the many negative

influences occurring during petitioner's childhood on petitioner's

psychological and social development.

More specifically, petitioner made no effort at

trial to elicit testimony from Ms. Mockeridge with regard to her

opinions that petitioner (1) felt abandoned and lacked a sense of

trust, (2) as a child, was preoccupied and oriented to a survival

mode, (3) lacked good coping skills, (4) had trust and abandonment

issues and the needs to belong and for safety, (5) developed

insecure, isolated, unhealthy relationships, (6) was failure-oriented,

possessed low self-concept, and felt hopeless, (7) learned

inappropriate responses, behaviors, and beliefs, (8) had a life

view characterized by hopelessness, lack of coping skills, poor

judgment, and impaired decision-making ability, (9) had a

distorted sense of reality and identity, low tolerance, no sense

of direction or purpose, and inappropriate responses, and (10) was

emotionally damaged, disabled, and dysfunctional, and used illegal

drugs to self-medicate to calm himself.

Petitioner's trial counsel likewise made no

effort to introduce properly authenticated copies of petitioner's

relevant school, medical, jail, and other records relied upon by

Ms. Mockeridge in the course of developing her psycho-social

history of petitioner. Likewise, petitioner's trial counsel made

no effort to introduce any testimony from petitioner's family,

friends, or others possessing personal knowledge regarding the

circumstances of petitioner's allegedly difficult childhood.

Instead, petitioner's trial counsel attempted, unsuccessfully, to

employ Ms. Mockeridge's status as an “expert” witness to

circumvent the Hearsay Rule and introduce rank hearsay information

about petitioner's childhood through her trial testimony.

The state trial court sustained the

prosecution's hearsay objections to these attempts, as well as the

prosecution's hearsay objections to Ms. Mockridge's written report

and a summary chart detailing the information she had acquired

while developing her psycho-social history of petitioner. In sum,

while the state trial court permitted Ms. Mockeridge to express

some of her expert opinions regarding the negative influences

affecting petitioner's development and petitioner's likely mental

condition at the time of his offense, the state trial court

excluded any and all hearsay testimony by Ms. Mockeridge detailing

precisely what information she had relied upon in arriving at her

opinions.

For unknown reasons, petitioner's trial counsel

made no effort to introduce in admissible form any of the

underlying evidence relied upon by Ms. Mockeridge in the course of

developing her expert opinions. For instance, petitioner's trial

counsel made no effort to secure and introduce certified, or

otherwise properly authenticated, copies of the petitioner's birth,

school, medical, mental health, juvenile, residency, or jail

records relied upon by Ms. Mockeridge in formulating her expert

opinions. Likewise, petitioner's trial counsel called no witnesses

possessing personal knowledge regarding the details of

petitioner's allegedly deprived childhood relied upon by Ms.

Mockeridge in developing her psycho-social history of petitioner.

Petitioner's trial counsel voiced no objection

to any of the trial court's evidentiary rulings concerning Ms.

Mockeridge. Petitioner's trial counsel made no proffer of

additional opinion testimony from Ms. Mockeridge along the lines

of that contained in her affidavit now before this Court. After

the jury began its deliberations at the punishment phase of

petitioner's capital trial, petitioner did move for the admission

of Ms. Mockeridge's written report, as well as her summary chart,

and the trial court admitted both for purposes of the record.

FN36. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, at pp. 199-201.

Petitioner raised no point of error on direct

appeal complaining about the trial court's rulings with regard to

Ms. Mockedridge's testimony, report, or chart.

In his original state habeas corpus application,

however, he complained for the first time that the trial court's

rulings regarding Ms. Mockeridge's testimony had effectively

precluded petitioner from presenting “mitigating” evidence to his

capital sentencing jury. FN37. State Habeas Transcript, at pp.

12-21.

The state habeas trial court (1) found the

trial court had ruled that Ms. Mockeridge, while not specifically

determined to be an expert on mitigation, would be permitted to

testify as an expert, (2) found the trial court sustained the

prosecution's hearsay objection to Ms. Mockeridge's summary chart,

(3) found Ms. Mockeridge was permitted to testify regarding the

nature of the documents and other evidence she had reviewed while

developing her psycho-social history of petitioner but was not

allowed to testify as to the specific contents of those hearsay

documents and conversations, (4) found Ms. Mockeridge was

permitted to express her opinions that numerous negative factors

impacted on petitioner's childhood development and that petitioner

was probably “in the midst of a substance[-]induced psychosis” at

the time of his offense, (5) found any confusion in the trial

court's rulings regarding Ms. Mockeridge's testimony excluded only

hearsay testimony on her part and not any expression of her expert

opinions, (6) found petitioner never complained to the trial court

that its rulings had impacted on petitioner's constitutional right

to present mitigating evidence, (7) concluded petitioner had

procedurally defaulted on his constitutional complaint regarding

the trial court's rulings on Ms. Mockeridge's testimony by failing

to timely make a bill of exceptions regarding same and failing to

present those complaints on direct appeal, (8) alternatively

concluded there was no error in the trial court's rulings on the

proper scope of Ms. Mockeridge's testimony.FN38 The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals subsequently adopted the trial court's findings

and conclusions when it denied state habeas corpus relief. Ex

parte Kevin Watts, WR-62,650-01 & WR-62,650-02 (Tex.Crim.App.

October 17, 2005). FN38. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 184-94.

C. Procedural Default

Respondent correctly points out that petitioner

procedurally defaulted on his complaints concerning the trial

court's rulings on Ms. Mockeridge's testimony by failing to timely

object on constitutional grounds to same and, thereafter, failing

to raise points of error on direct appeal challenging the trial

court's rulings.

1. Failure to Make a Contemporaneous

Objection

Petitioner's failure to contemporaneous object

to the state trial court's allegedly “limiting” rulings regarding

the admissibility of Ms. Mockeridge's testimony, written report,

and summary chart constitutes a form of procedural default, which

serves as a barrier to federal habeas review of this claim. See

Johnson v. Cain, 215 F.3d 489, 495 (5th Cir.2000) (holding a

federal district court may raise the issue of procedural default

sua sponte); Magouirk v. Phillips, 144 F.3d 348, 358 (5th

Cir.1998)(holding the same).

In point of fact, petitioner failed to make any

proffer at trial, and likewise failed to obtain a state trial

court ruling specifically addressing the admissibility, of the

additional opinion testimony contained in Ms. Mockeridge's

affidavit now before this Court. Simply put, the state trial court

never had an opportunity to address specifically the admissibility

of Ms. Mockeridge's additional opinion testimony, proffered for

the first time in her affidavit which accompanied petitioner's

initial state habeas corpus application.

Procedural default occurs where (1) a state

court clearly and expressly bases its dismissal of a claim on a

state procedural rule, and that procedural rule provides an

independent and adequate ground for the dismissal, or (2) the

petitioner fails to exhaust all available state remedies, and the

state court to which he would be required to petition would now

find the claims procedurally barred. Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S.

722, 735 n. 1, 111 S.Ct. 2546, 2557 n. 1, 115 L.Ed.2d 640 (1991).

In either instance, the petitioner is deemed to

have forfeited his federal habeas claim. O'Sullivan v. Boerckel,

526 U.S. 838, 848, 119 S.Ct. 1728, 1734, 144 L.Ed.2d 1 (1999).

Procedural defaults only bar federal habeas review when the state

procedural rule which forms the basis for the procedural default

was “firmly established and regularly followed” by the time it was

applied to preclude state judicial review of the merits of a

federal constitutional claim. Ford v. Georgia, 498 U.S. 411, 424,

111 S.Ct. 850, 857-58, 112 L.Ed.2d 935 (1991).

Petitioner alleges no facts, and cites this

Court to no Texas case law, showing the Texas courts have

inconsistently applied the contemporaneous objection rule in

similar contexts, i.e., with regard to alleged errors in the

admission of evidence. More specifically, petitioner identifies no

instances in which the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has

entertained the merits of a claim challenging the

constitutionality of a state trial court's ruling on the

admissibility of potentially mitigating evidence at the punishment

phase of a capital trial when raised for the first time in a state

habeas corpus application.

The Fifth Circuit has long recognized a federal

habeas petitioner's failure to comply with the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule as an adequate and independent

state procedural barrier to federal habeas review. See Rowell v.

Dretke, 398 F.3d 370, 375-75 (5th Cir.2005) (holding a defendant's

failure to timely object to alleged errors in a jury charge

determined by a Texas appellate court to be a violation of the

Texas contemporaneous objection rule barred federal habeas relief

of the alleged erroneous jury charge under the procedural default

doctrine), cert. denied, 546 U.S. 848, 126 S.Ct. 103, 163 L.Ed.2d

117 (2005); Graves v. Cockrell, 351 F.3d 143, 152 (5th Cir.2003)

(Texas contemporaneous objection rule is an adequate and

independent state ground and failure to comply with this rule

procedurally bars federal habeas review), cert. denied, 541 U.S.

1057, 124 S.Ct. 2160, 158 L.Ed.2d 757 (2004); Cotton v. Cockrell,

343 F.3d 746, 754 (5th Cir.2003) (holding violation of the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule is an adequate and independent

barrier to federal habeas review), cert. denied, 540 U.S. 1186,

124 S.Ct. 1417, 158 L.Ed.2d 92 (2004); Dowthitt v. Johnson, 230

F.3d 733, 752 (5th Cir.2000)(holding the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule is strictly or regularly and evenhandedly applied

in the vast majority of cases and, therefore, an adequate state

bar), cert. denied, 532 U.S. 915, 121 S.Ct. 1250, 149 L.Ed.2d 156

(2001); Barrientes v. Johnson, 221 F.3d 741, 779 (5th Cir.2000)(failure

to timely object waives error in jury instructions unless the

error is so prejudicial no instruction could cure the error), cert.

denied, 531 U.S. 1134, 121 S.Ct. 902, 148 L.Ed.2d 948 (2001);

Muniz v. Johnson, 132 F.3d 214, 221 (5th Cir.1998) (Texas courts

strictly and regularly apply the Texas contemporaneous objection

rule which is an adequate state procedural rule), cert. denied,

523 U.S. 1113, 118 S.Ct. 1793, 140 L.Ed.2d 933 (1998); Sharp v.

Johnson, 107 F.3d 282, 285-86 (5th Cir.1997) (holding the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule is an independent and adequate

state ground upon which to base a procedural bar to federal review);

Rogers v. Scott, 70 F.3d 340, 342 (5th Cir.1995)(holding a federal

habeas petitioner's failure to comply with the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule also bars federal habeas review of

a claim absent cause and prejudice or a fundamental miscarriage of

justice), cert. denied, 517 U.S. 1235, 116 S.Ct. 1881, 135 L.Ed.2d

176 (1996); Nichols v. Scott, 69 F.3d 1255, 1278 n. 44 (5th

Cir.1995) (holding the same), cert. denied, 518 U.S. 1022, 116

S.Ct. 2559, 135 L.Ed.2d 1076 (1996); Amos v. Scott, 61 F.3d 333,

338-45 (5th Cir.1995)(holding the same), cert. denied, 516 U.S.

1005, 116 S.Ct. 557, 133 L.Ed.2d 458 (1995).

More importantly, the Fifth Circuit has

recognized the efficacy of the Texas contemporaneous objection

rule as a barrier to federal habeas review was “firmly established”

for federal procedural default purposes long before the date

petitioner filed his brief on direct appeal. See Hogue v. Johnson,

131 F.3d 466, 487 (5th Cir.1997) (holding the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule was already well established 35

years ago and recognized as an adequate state procedural barrier

to federal habeas review at least twenty years ago), cert. denied,

523 U.S. 1014, 118 S.Ct. 1297, 140 L.Ed.2d 334 (1998); Rogers v.

Scott, 70 F.3d at 342 (recognizing the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule foreclosed federal habeas review); Amos v. Scott,

61 F.3d at 343-44 (holding Texas appellate courts consistently

apply the contemporaneous objection rule in the vast majority of

cases and, thereby, strictly and regularly apply same).

Petitioner's trial counsel wholly failed to

present the trial court with any opportunity to rule on the

admissibility of Ms. Mockeridge's additional opinion testimony,

i.e., that contained in her affidavit now before this Court.

Petitioner failed to obtain a state trial court ruling regarding

the admissibility of the vast bulk of Ms. Mockeridge's recently-proffered

opinion testimony and failed to object to any ruling by the trial

court purporting to limit the scope of Ms. Mockeridge's opinion

testimony. For those reasons, petitioner procedurally defaulted on

his first claim for federal habeas relief herein.

2. Failure to Raise Claim on Direct Appeal

Likewise, the Fifth Circuit has long recognized

the efficacy of the Texas procedural rule requiring presentation

of claims about allegedly erroneous trial court rulings on direct

appeal. Petitioner identifies no instances in which the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals has entertained the merits of a federal

constitutional claim about a state trial court's allegedly

erroneous evidentiary ruling when that claim was raised for the

first time in a state habeas corpus application.

More importantly, the Fifth Circuit has

recognized that the same procedural default rule relied upon by

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in its adopted findings and

conclusions denying petitioner state habeas corpus relief was

“firmly established” for federal procedural default purposes

before the date the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals disposed of

petitioner's direct appeal. See Busby v. Dretke, 359 F.3d 708, 719

(5th Cir.2004), (holding the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals'

opinion in Ex parte Gardner, 959 S.W.2d 189, 199 (Tex.Crim.App.1996)

modified on motion for rehearing on February 2, 1998, to recognize

this new procedural default rule, “firmly entrenched” that

procedural default rule on that date), cert. denied, 541 U.S.

1087, 124 S.Ct. 2812, 159 L.Ed.2d 249 (2004); Finley v. Johnson,

243 F.3d 215, 219 (5th Cir.2001) (holding a federal habeas

petitioner procedurally defaulted on an unexhausted newly

discovered evidence theory supporting a Brady claim by failing to

raise same on direct appeal); Soria v. Johnson, 207 F.3d 232, 249

(5th Cir.2000) (holding a federal habeas petitioner procedurally

defaulted on a fair cross-section complaint by failing to raise it

in a direct appeal that became final in 1997), cert. denied, 530

U.S. 1286, 121 S.Ct. 2, 147 L.Ed.2d 1027 (2000).

At the time petitioner filed his appellant's

brief the law in Texas, as established on rehearing in Ex parte

Gardner, required a convicted criminal defendant to present any

and all claims then available as points of error on direct appeal.

Id. For unknown reasons, petitioner's appellate counsel failed to

assert petitioner's complaint regarding the trial court's rulings

on Ms. Mockeridge's testimony as a point of error on direct

appeal. Thus, petitioner has procedurally defaulted on this claim

in this Court.

Petitioner has twice procedurally defaulted on

his federal claim arising from the trial court's allegedly

restrictive or limiting rulings on Ms. Mockeridge's testimony.

3. Exceptions Inapplicable

Petitioner's failures to make a timely

constitutional objection to the state trial court's allegedly

“restrictive” or “limiting” rulings on the admissibility of Ms.

Mockeridge's punishment-phase testimony or to raise points of

error complaining about same on direct appeal bar federal habeas

review of petitioner's constitutional challenge to those rulings

unless petitioner can satisfy one of the two exceptions to the

procedural default doctrine.

The Supreme Court has recognized exceptions to

the doctrine of procedural default where a federal habeas corpus

petitioner can show “cause and actual prejudice” for his default

or that failure to address the merits of his procedurally

defaulted claim will work a “fundamental miscarriage of justice.”

Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. at 750, 111 S.Ct. at 2565; Harris v.

Reed, 489 U.S. 255, 262, 109 S.Ct. 1038, 1043, 103 L.Ed.2d 308

(1989). To establish “cause,” a petitioner must show either that

some objective external factor impeded the defense counsel's

ability to comply with the state's procedural rules or that

petitioner's trial or appellate counsel rendered ineffective

assistance. Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. at 753, 111 S.Ct. at

2566; Murray v. Carrier, 477 U.S. 478, 488, 106 S.Ct. 2639, 2645,

91 L.Ed.2d 397 (1986) (holding that proof of ineffective

assistance by counsel satisfies the “cause” prong of the exception

to the procedural default doctrine).

While a showing of ineffective assistance can

satisfy the “cause” prong of the “cause and actual prejudice”

exception to the procedural default doctrine, petitioner does not

allege any specific facts in this Court establishing that his

trial counsel's failure to assert a constitutional challenge to

the trial court's rulings on Ms. Mockerdige's testimony or his

appellate counsel's failure to present points of error on direct

appeal complaining about same satisfy either prong of the

Strickland v. Washington test for ineffective assistance.

In order to satisfy the “miscarriage of justice”

test, the petitioner must supplement his constitutional claim with

a colorable showing of factual innocence. Sawyer v. Whitley, 505

U.S. 333, 335-36, 112 S.Ct. 2514, 2519, 120 L.Ed.2d 269 (1992). In

the context of the punishment phase of a capital trial, the

Supreme Court has held that a showing of “actual innocence” is

made when a petitioner shows by clear and convincing evidence that,

but for constitutional error, no reasonable juror would have found

petitioner eligible for the death penalty under applicable state

law. Sawyer v. Whitley, 505 U.S. at 346-48, 112 S.Ct. at 2523.

The Supreme Court explained in Sawyer v.

Whitley this “actual innocence” requirement focuses on those

elements which render a defendant eligible for the death penalty

and not on additional mitigating evidence that was prevented from

being introduced as a result of a claimed constitutional error.

Sawyer v. Whitley, 505 U.S. at 347, 112 S.Ct. at 2523. Petitioner

has alleged no specific facts satisfying this “factual innocence”

standard. At the punishment phase of petitioner's capital trial,

Ms. Mockeridge made the jury aware of the fact there had been many

negative influences on petitioner's childhood development.FN39

Petitioner's cousins informed the jury the petitioner was involved

with gangs and drugs by the time he arrived in Texas at age

fourteen.FN40 Thus, Ms. Mockeridge's additional opinion testimony,

proffered in her affidavit, offers little in the way of additional

substantive evidence regarding petitioner's background or moral

culpability for his capital offense sufficient to have earned

petitioner a life sentence.

FN39. S.F. Trial, Volume 24 of 26, testimony of

Linda Mockeridge, at pp. 130-31. FN40. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of

26, testimony of Sonia Watts, at pp. 171-72, 205; testimony of

Ronald Melvin Watts, at pp. 227-28.

Given the record now before this Court which

establishes the heinous nature of petitioner's offense,

petitioner's equally remorseless conduct toward Hye Kyong Kim in

the hours after his capital offense, and petitioner's complete

failure to express any genuine remorse personally or to make a

sincere personal expression of contrition for his murderous

conduct before the jury, petitioner has failed to establish by

“clear and convincing evidence” that, but for the trial court's

allegedly erroneous evidentiary rulings, no reasonable jury could

have found him eligible for the death sentence.

In short, the evidence of petitioner's long

history of violent behavior, propensity for future criminal

conduct, and utter lack of remorse for his criminal misbehavior

was overwhelming. Even considering petitioner's additional opinion

testimony from Ms. Mockeridge, in the absence of any scintilla of

evidence showing the petitioner ever personally expressed remorse

for his capital offense before his capital sentencing jury, there

is not even a remote possibility, much less clear and convincing

evidence, that, but for the absence of Ms. Mockeridge's additional

opinion testimony, a rational jury could have found petitioner

ineligible for the death penalty. Because petitioner has failed to

satisfy the “actual innocence” test, he is not entitled to relief

from his procedural defaults under the fundamental miscarriage of

justice exception to the procedural default doctrine.

D. No Merits

Federal habeas corpus relief will not issue to

correct errors of state constitutional, statutory, or procedural

law, unless a federal issue is also presented. Estelle v. McGuire,

502 U.S. 62, 67-68, 112 S.Ct. 475, 480, 116 L.Ed.2d 385

(1991)(holding complaints regarding the admission of evidence

under California law did not present grounds for federal habeas

relief absent a showing that admission of the evidence in question

violated due process); Lewis v. Jeffers, 497 U.S. 764, 780, 110

S.Ct. 3092, 3102, 111 L.Ed.2d 606 (1990) (recognizing that federal

habeas relief will not issue for errors of state law); Pulley v.

Harris, 465 U.S. 37, 41, 104 S.Ct. 871, 874, 79 L.Ed.2d 29

(1984)(holding a federal court may not issue the writ on the basis

of a perceived error of state law).

In the course of reviewing state criminal

convictions in federal habeas corpus proceedings, a federal court

does not sit as a super-state appellate court. Estelle v. McGuire,

502 U.S. at 67-68, 112 S.Ct. at 480; Lewis v. Jeffers, 497 U.S. at

780, 110 S.Ct. at 3102; Pulley v. Harris, 465 U.S. at 41, 104 S.Ct.

at 874. “When a federal district court reviews a state prisoner's

habeas petition pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254 it must decide

whether the petitioner is ‘in custody in violation of the

Constitution or laws or treaties of the United States.’ The court

does not review a judgment, but the lawfulness of the petitioner's

custody simpliciter.” Coleman v. Thompson, 501 U.S. at 730, 111

S.Ct. at 2554.

A federal court may grant habeas relief based

on an erroneous state court evidentiary ruling only if the ruling

violates a specific federal constitutional right or is so

egregious it renders the petitioner's trial fundamentally unfair.

Brown v. Dretke, 419 F.3d 365, 376 (5th Cir.2005), cert. denied,

546 U.S. 1217, 126 S.Ct. 1434, 164 L.Ed.2d 137 (2006); Wilkerson

v. Cain, 233 F.3d 886, 890 (5th Cir.2000); Johnson v. Puckett, 176

F.3d 809, 820 (5th Cir.1999). The failure to admit evidence

amounts to a due process violation only when the omitted evidence

is a crucial, critical, highly significant factor in the context

of the entire trial. Johnson v. Puckett, 176 F.3d at 821.

Thus, the question before this Court is not

whether the state trial court properly applied state evidentiary

rules but, rather, whether petitioner's federal constitutional

rights were violated by any ruling made by the trial court in

admitting or excluding evidence actually proffered for admission

during petitioner's trial. See Bigby v. Dretke, 402 F.3d 551, 563

(5th Cir.2005) (holding federal habeas review of a state court's

evidentiary ruling focuses exclusively on whether the ruling

violated the federal Constitution), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----,

126 U.S. 239, 163 L.Ed.2d 221 (2005).

None of the many Supreme Court opinions cited

by petitioner in support of his first claim for relief herein

holds that the Eighth Amendment abrogates state evidentiary rules,

including the Hearsay Rule. On the contrary, the Fifth Circuit has

upheld against a due process challenge a state trial court's

exclusion during the punishment phase of a capital trial of an

expert's proffered hearsay testimony regarding out-of-court

statements made to the expert by the defendant. See McGinnis v.

Johnson, 181 F.3d 686, 693 (5th Cir.1999) (holding there was no

due process violation where the state trial court permitted the

expert to testify as to his opinions about the petitioner's state

of mind during and after the crime arising from petitioner's

statements to the expert but excluded the petitioner's statements

to the expert), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1125, 120 S.Ct. 955, 145

L.Ed.2d 829 (2000).

The Fifth Circuit's holding in McGinnis

controls the disposition of petitioner's initial claim for relief

herein. Petitioner's trial court (1) permitted Ms. Mockeridge to

opine regarding her beliefs that (a) petitioner had been

negatively impacted by numerous factors during his childhood and

(b) petitioner was likely suffering from substance-induced

psychosis at the time of his capital offense but (2) refused to

permit Ms. Mockeridge to testify regarding hearsay statements made

to her by petitioner and others or about hearsay information

contained in documents petitioner never proffered for admission in

properly authenticated form.

The state trial court's rulings concerning Ms.

Mockeridge's testimony did not render petitioner's trial

fundamentally unfair. Petitioner's trial counsel made no effort

whatsoever to elicit any opinion testimony from Ms. Mockeridge

along the lines of that contained in her affidavit now before this

Court. More specifically, petitioner made no effort at his trial

to present the jury with opinion testimony by Ms. Mockeridge

regarding the impact of the many negative influences on

petitioner's development on petitioner's character.

For instance, Ms. Mockeridge opines in her

affidavit that petitioner suffered from (1) feelings of

hopelessness, abandonment, and isolation, (2) a pathological need

for belonging, (3) a lack of coping skills, (4) an inability to

engage in appropriate behavior, (5) emotional damage, and (6) a

preoccupation with survival behavior. However, petitioner's trial

counsel made no effort to elicit similar testimony from Ms.

Mockeridge during the punishment phase of petitioner's trial.

Petitioner cannot fault the state trial court for what was

apparently the wholesale deficient performance of his trial

counsel in failing to either (1) attempt to elicit similar

testimony or (2) obtain a clarifying ruling from the trial court

regarding the admissibility of such testimony. It is disingenuous

for petitioner to make no effort to secure a specific trial court

ruling on the admissibility of particular opinion testimony and

then to complain the trial court's allegedly ambiguous rulings on

hearsay matters somehow dissuaded petitioner from even offering

that same opinion testimony.

When viewed in the context of petitioner's

entire trial, there was nothing crucial, critical, or highly

significant about any of the additional opinion testimony from Ms.

Mockeridge petitioner now claims he was somehow prevented from

eliciting from that witness during the punishment phase of his

capital trial. It is significant that the trial court's only

rulings excluding testimony by Ms. Mockeridge addressed efforts by

petitioner's trial counsel to do an end-run around the Hearsay

Rule by having Ms. Mockeridge testify as to information which she

either (1) was told by petitioner or his family or (2) read in

wholly hearsay documents which had never been proffered for

admission into evidence at petitioner's trial. The state trial

court cannot reasonably be faulted for enforcing the Texas Hearsay

Rule. Nor can the state trial court be faulted for “excluding” Ms.

Mockeridge's opinion testimony where (1) the trial court permitted

her to testify fully concerning her opinion of the petitioner's

mental state at the time of his offense and (2) the petitioner

made no effort at trial to offer additional opinion testimony from

Ms. Mockeridge concerning the other matters set forth in her post-trial

affidavit. While petitioner correctly argues the Eighth Amendment

ensures a capital defendant the opportunity to present relevant

mitigating evidence, nothing in the federal Constitution abrogates

state evidentiary rules. See McGinnis v. Johnson, 181 F.3d at 693

(holding there was no violation of due process where a defense

expert was permitted to testify at the punishment phase of a

capital trial regarding his opinion of the defendant's mental

state at the time of the offense but was precluded from testifying

regarding the specific contents of hearsay statements made by the

defendant which helped form the basis for the expert's opinion).

E. Conclusions

Petitioner procedurally defaulted on his

initial claim for federal habeas relief herein by failing to

timely object to, or otherwise properly preserve for state

appellate review, his complaint about the trial court's allegedly

limiting rulings regarding Ms. Mockeridge's testimony. In fact,

petitioner made no effort to obtain a ruling from the trial court

on the admissibility of the vast majority of Ms. Mockeridge's

opinion testimony which petitioner now claims he was somehow

precluded from introducing at trial.

Furthermore, petitioner procedurally defaulted

a second time on this same claim of allegedly erroneous trial

court evidentiary rulings by failing to raise his complaints on

direct appeal. Petitioner has alleged no specific facts sufficient

to overcome either of his two, separate, procedural defaults on

his first federal habeas claim. The state habeas court's

alternative conclusion that petitioner's federal constitutional

rights were not violated by the trial court's evidentiary rulings

is consistent with the Fifth Circuit's squarely-on-point holding

in McGinnis.

Under such circumstances, the state habeas

court's alternative ruling that there was no federal

constitutional error arising from the trial court's rulings on the

admissibility of Ms. Mockeridge's testimony, written report, and

summary chart was neither contrary to, nor involved an

unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as

determined by the Supreme Court of the United States, nor an

unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence

presented in the petitioner's state habeas corpus proceeding.

IV. Dawson v. Delaware Claim

A. The Claim

In his second claim herein, petitioner argues

his First Amendment rights, as recognized by the Supreme Court in

Dawson v. Delaware, 503 U.S. 159, 112 S.Ct. 1093, 117 L.Ed.2d 309

(1992), were violated when the trial court admitted the letter

petitioner wrote to his cousin from jail while awaiting trial for

capital murder, which contained several ethnic slurs and indicated

petitioner's desire to assault others and join a prison gang

identified therein by petitioner as the “Black Gorilla Family,”

i.e., State Exhibit No. 105-A. FN41. Petition, docket entry no. 6,

at pp. 17-18.

B. State Court Disposition

When the prosecution offered State Exhibit no.

105-A at trial, the only objections petitioner's trial counsel

raised were arguments that jail personnel had unlawfully tampered

with, examined, and seized petitioner's private

correspondence.FN42 At no time did petitioner's trial counsel

raise an objection that the admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A

violated petitioner's First Amendment right to association

recognized by the Supreme Court's holding in Dawson v. Delaware.

FN42. S.F. Trial, Volume 23 of 26, testimony of Mark Wells, at pp.

81-94.

In his first point of error on direct appeal,

petitioner argued the state trial court violated the Supreme

Court's holding in Dawson v. Delaware when it admitted evidence of

petitioner's desire for membership in “a black racist prison gang.”

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (1) found petitioner never

objected at trial to the admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A on

Dawson or First Amendment grounds, (2) found petitioner's trial

objections to the admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A and to

related testimony made no mention of gang membership, and (3)

concluded petitioner failed to properly preserve for state

appellate review any federal constitutional objection to the

admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A or any trial testimony

concerning same. FN43. Watts v. State, AP-74,593 (Tex.Crim.App.

December 15, 2004). A copy of this unpublished opinion is attached

to Petitioner's Petition herein at exhibit B.

In his initial state habeas corpus application,

petitioner again urged his complaint that the admission of State

Exhibit no. 105-A violated his federal constitutional right to

association.FN44 The state habeas trial court (1) found

petitioner's trial counsel first raised the issue of gang

membership at trial, (2) found there was no dispute that

petitioner had admitted to having been a member of the Longview

Crips street gang, (3) found no evidence was admitted identifying

either the Longview Crips, i.e., the California street gang to

which petitioner admitted once having been a member, or the Black

Gorilla Family, i.e., the prison gang to which petitioner wrote he

planned to seek membership, as “racist” gangs, (4) found

petitioner made no constitutional objection to the admission of

any evidence showing petitioner was either a member of the

Longview Crips or hoped to one day be a member of the Black

Gorilla Family, (5) concluded the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

had held on direct appeal that petitioner procedurally defaulted

on this same constitutional claim by failing to timely object at

trial to the admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A on the same

ground as that now urged by petitioner, and (6) alternatively

concluded no constitutional error arose from the admission of

State Exhibit no. 105-A.FN45

FN44. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 21-23.

FN45. State Habeas Transcript, at pp. 196-202.

C. Procedural Default

Respondent correctly argues that petitioner has

procedurally defaulted on this claim by failing to timely object

at trial to the admission of State Exhibit no. 105-A on the same

federal constitutional ground petitioner initially urged on direct

appeal and now urges before this Court.

Generally speaking, Texas law requires an

objection to coincide with a point of error on direct appeal. See,

e.g., Guevara v. State, 97 S.W.3d 579, 583 (Tex.Crim.App.2003), (defendant

failed to preserve complaint regarding the admission of victim-impact

evidence by objecting thereto only on the ground that the witness

was unqualified to render an opinion regarding the impact of the

crime on the victim's personality); Ibarra v. State, 11 S.W.3d

189, 196-97 (Tex.Crim.App.1999) (holding a hearsay objection did

not preserve for appellate review a complaint that the testimony

in question was irrelevant), cert. denied, 531 U.S. 828, 121 S.Ct.

79, 148 L.Ed.2d 41 (2000).

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals'

determination on direct appeal, as well as the state habeas

court's similar determination, that petitioner's trial counsel's

objections to the petitioner's allegedly improperly-seized

correspondence failed to properly preserve petitioner's

constitutional complaint about the admission of State Exhibit no.

105-A appear to be straight-forward applications of this “firmly

established and regularly followed” principle of state criminal

procedure.

By failing to present the trial court with a

contemporaneous objection to the admission of State Exhibit no.

105-A which mirrored the First Amendment complaints petitioner

subsequently presented on direct appeal and in his state habeas

corpus proceeding, petitioner procedurally defaulted on his Dawson