NO. 73,058

CHUONG DUONG TONG, Appellant

THE STATE OF TEXAS

Delivered: April 13, 2000

Meyers, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which McCormick, P.J., and Keller, Price, Holland, and Keasler joined. Johnson, J., filed a dissenting opinion in which Mansfield and Womack, J.J., joined.

Appellant was convicted of capital murder in March, 1998. Tex. Penal Code Ann. 19.03(a). Pursuant to the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure article 37.071 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to death. Art. 37.071 2(g).(1) Direct appeal to this Court is automatic. Art. 37.071 2(h). Appellant raises eighteen points of error, but does not challenge the sufficiency of the evidence to support either his conviction or his punishment. We affirm.

In his first point of error, appellant complains that the trial judge abused his discretion by changing the method of jury selection in the middle of voir dire. Appellant asserts that this change prevented him from intelligently utilizing his peremptory challenges, thus denying him the effective assistance of counsel, due process of law, and due course of law.

According to appellant, the judge assured him at the beginning of trial that he "would be given as many peremptory challenges as he requested,"(2) and he relied on this promise in conducting his voir dire. However, appellant contends that, as they were nearing the end of voir dire, the trial judge abruptly returned to "the old-fashioned way," but refused to restore any of his strikes. Hence, appellant claims he went from a position of having unlimited strikes to a position of having no strikes, which harmed him by subsequently forcing him to accept an undesirable juror.

Appellant maintains that the trial court's decision to alter its voir dire procedure deprived appellant of due process of law, due course of law and the effective assistance of counsel.(3) However, appellant fails to cite any relevant authority, from this jurisdiction or from any other, to support his constitutional claims.

In fact, Appellant cites only one case which he maintains is favorable to his position. Specifically, he asserts that Sanne v. State, 609 S.W.2d 762, 767 (Tex. Crim. App. 1980), supports his constitutional claim. However, we can find nothing in Sanne that can be read to support appellant's argument.

That case dealt with a facial constitutional challenge to the statutory requirement in death penalty cases that the parties exercise peremptory challenges after examination of individual venire persons, rather than being able to use peremptories after having seen the entire venire. Sanne neither deals with the same issue presented in the instant case, nor provides any relevant constitutional or statutory framework for evaluating his claim.

This is not to say that appellant may not make a novel argument for which there is no authority directly on point. However, in making such an argument, appellant must ground his contention in analogous case law or provide the Court with the relevant jurisprudential framework for evaluating his claim. In failing to provide any relevant authority suggesting how the judge's actions violated any of appellant's constitutional rights, we find the issue to be inadequately briefed. See Tex. R. App. P. 38.1(h); see also McDuff v. State, 939 S.W.2d 607, 621 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997). Appellant's first point of error is overruled.

In his fourth point of error, appellant charges that his capital punishment proceedings violated the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Specifically, he notes that the trial court instructed the jury that it could not be influenced by "sympathy" when answering the special issues.(4)

Appellant maintains that this "anti-sympathy" charge misled jurors into thinking that it would be improper for them to consider sympathy based on mitigating evidence, which might ultimately have led them to conclude that a life sentence was more appropriate than death.

Appellant's assertion is contrary to the law. As we recently reiterated in Prystash v. State, 3 S.W.3d 522, 534-35 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999), evidence that relies on mere sympathy or emotional response is irrelevant to the jury's consideration of the deathworthiness of the defendant. See also Rhoades v. State, 934 S.W.2d 113, 126 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996) (finding photographs of defendant which depict cheerful early childhood irrelevant because such evidence has no relationship to defendant's conduct); Goff v. State, 931 S.W.2d 537, 555-56 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996) (homosexuality of victim, if unknown to defendant and unrelated to crime, irrelevant to jury's ability to consider and give mitigating effect to background or character of defendant). Indeed, we have held that anti-sympathy charges are appropriate in that they properly focus the jury's attention on those factors relating to the moral culpability of the defendant. See McFarland v. State, 928 S.W.2d 482, 522 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996). Nor do such charges unconstitutionally contradict mitigation instructions. See Fuentes v. State, 991 S.W.2d 267, 276-77 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999); Green v. State, 912 S.W.2d 189, 195 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995). Appellant's fourth point of error is overruled.

In his fifth point of error, appellant contends that the trial court erred by refusing to instruct the jury that they could not consider unadjudicated offenses unless the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant committed those acts. Such an instruction is not required when, as was done in the instant case, the special issues include an instruction on the State's burden of proof. Jackson v. State, 992 S.W.2d 469, 477 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). Point of error five is overruled.

Appellant argues in his seventh point of error that the admission of unadjudicated extraneous offenses at punishment violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This Court has held on a number of occasions that Article 37.071, which controls the sentencing phase of a capital murder trial, allows the admission of unadjudicated extraneous offenses at punishment and that this practice does not violate Fourteenth Amendment. See, e.g., Cockrell v. State, 933 S.W.2d 73, 93-94 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996). Appellant recognizes this line of cases, but argues that they should be overturned. This we decline to do. Point of error seven is overruled.

In his fifteenth point of error, appellant argues that the Eighth Amendment erects a per se bar to victim character/impact evidence. Appellant recognizes that we have already addressed and rejected an identical argument in Mosley v. State, 983 S.W.2d 249, 261-265 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 1466 (1999); see also Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 825 (1991). We decline appellant's invitation to reconsider that decision. Point of error fifteen is overruled.

In his sixteenth point of error, appellant asserts that he is entitled to a new trial on punishment so that his defense counsel "may make the choice this Court declared available in Mosley v. State (decided after appellant's trial), that is, whether to waive the mitigation issue entirely as a means of preventing the introduction of any victim [character/impact] evidence." Appellant claims that the law that existed at the time of his trial prevented him from waiving the mitigation issue. He argues that had the law given him the opportunity that Mosley provides, he would have been able to prevent the State from introducing any victim impact evidence.

This Court's opinion in Mosley did not create, as appellant maintains, a new rule regarding waiver of the mitigation special issue. To date, this Court has not decided whether a capital defendant can waive that issue.(5) Cf. Prystash v. State, 3 S.W.3d 522, 532 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999).

The statement in Mosley that appellant claims created a "newly announced waiver choice" was not necessary to the holding in that case and is therefore dicta. It is true that the majority in Mosley suggested that a defendant could waive reliance upon and submission of the mitigation issue, thereby rendering victim impact and character evidence irrelevant and inadmissible. See Art. 37.071 2(e); Mosley, 983 S.W.2d at 264. However, this statement was made in connection with several points concerning victim impact evidence, and the holding under these points pertains to the admissibility of the victim impact evidence, not whether the special issue can be waived. Point of error sixteen is overruled.

In seven separate points of error, appellant claims that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance under the state and federal constitutions. When confronted with an ineffective assistance of counsel claim from either stage of a capital trial, we apply the two-pronged analysis set forth by the United States Supreme Court in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984). See Hernandez v. State, 726 S.W.2d 53 (Tex. Crim. App. 1986) (adopting Strickland as applicable standard under Texas Constitution).

Under the first prong of the Strickland test, an appellant must show that counsel's performance was "deficient." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687. "This requires showing that counsel made errors so serious that counsel was not functioning as the 'counsel' guaranteed the defendant by the Sixth Amendment." Id.

To be successful in this regard, an appellant "must show that counsel's representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness." Id. at 688. Under the second prong, an appellant must show that the deficient performance prejudiced the defense. Id. at 687.

The appropriate standard for judging prejudice requires an appellant to "show that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different. A reasonable probability is a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the outcome." Id. at 694. Appellant must prove both prongs of Strickland by a preponderance of the evidence in order to prevail. McFarland v. State, 845 S.W.2d 824, 842 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992).

The review of defense counsel's representation at trial is highly deferential. We engage in "a strong presumption" that counsel's actions fell within the wide range of reasonably professional assistance. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 689. It is appellant's burden to overcome the presumption that, under the circumstances, the challenged action might be considered sound trial strategy. Id.; see also Chambers v. State, 903 S.W.2d 21, 33 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995).

In his second and third points of error, appellant asserts that his counsel was ineffective at the punishment stage of trial for failing to object to the State's arguments interpreting the mitigation instruction as "limiting jurors to considering only those facts that they found reduced appellant's moral blameworthiness, and interpreting the instructions to prohibit any consideration of sympathy for appellant."(6)

In its punishment charge, the trial court instructed the jurors that when answering the special issues they were "not to be swayed by mere sentiment, conjecture, sympathy, passion, prejudice, public opinion or public feeling" in considering the evidence. He further instructed the jury that in answering the mitigation special issue, the jury should consider "mitigating" evidence

to be evidence that a juror might regard as reducing the defendant's moral blameworthiness, including, but not limited to, evidence of the defendant's background and character, or the circumstances of the offense that mitigates against the imposition of the death penalty.

See Art. 37.071 2(f)(4). These statements were proper recitations of the law. See Prystash v. State, 3 S.W.3d 522, 534-35 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) (evidence that relies on mere sympathy or emotional response is irrelevant to the jury's consideration of the deathworthiness of the defendant); McFarland, 928 S.W.2d at 522 (anti-sympathy charge properly focuses attention of the jury on those factors relating to a moral inquiry into the culpability of the defendant).

The argument about which appellant complains was merely a reiteration of the law on which the jury was charged and was, therefore, proper argument. See Lagrone v. State, 942 S.W.2d 602, 619 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997). As such, defense counsel did not fall below an "objective standard of reasonableness" for failing to object. Points of error two and three are overruled.

In his sixth point of error, appellant alleges that his trial counsel was ineffective at punishment for failing to inform the jury in his final argument that the burden of proof on the future dangerousness issue implicitly included the burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant committed the unadjudicated extraneous offenses.

Further, appellant asserts that his counsel should have informed the jury that the State had to meet this burden before the jury could use evidence of the extraneous offenses in answering the special issues. In effect, appellant argues that it was incumbent upon defense counsel to go beyond the jury charge and instruct the jury that the State's burden on the extraneous offenses was subsumed within the general burden on the special issues. There is no such duty under the law.

The jury was properly instructed regarding the burden of proof concerning the special issues. We have held that a trial court does not err in failing to submit in the punishment jury charge a separate instruction on the burden of proof on extraneous offenses. See Kutzner v. State, 994 S.W.2d 180, 188 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999).

The jury therefore was given the proper legal framework for deciding the case. The points of the charge that defense counsel chose to emphasize in argument were a matter properly left to the realm of trial strategy. Hence, we cannot say that trial counsel was ineffective for failing to make this argument. Point of error six is overruled.

In his seventeenth point of error, appellant submits that his counsel was ineffective for failing to object to victim testimony concerning victims not named in the indictment.(7) Specifically, appellant complains about the testimony of two witnesses, Vincent and Hanah Lee, who were victims of an unadjudicated extraneous burglary/aggravated robbery that appellant allegedly committed.(8) The prosecutor elicited testimony from both of the Lees regarding the effect the event had on their lives.

Impact testimony from the victims of an extraneous offense is not the type of "victim impact evidence" contemplated by Mosley and Payne v. Tennessee, and therefore, was arguably objectionable.(9) Payne, 501 U.S. 808, 825 (1991); Mosley, 983 S.W.2d at 261-265; see also Cantu v. State, 939 S.W.2d 627 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997).

However, the record in the instant case is silent as to why appellant's counsel failed to object and is therefore insufficient to overcome the presumption that counsel's actions were part of a strategic plan.(10) See Thompson v. State, 9 S.W.3d 808, 814 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). Point of error seventeen is overruled.

In his eighteenth point of error, appellant submits that his counsel was ineffective at punishment for failing to object to victim testimony in which the victims expressed their opinions of appellant and their wish that he receive the death penalty. While this may have also been objectionable testimony, without some explanation as to why counsel acted as he did, we presume that his actions were the product of an overall strategic design.(11) See Thompson, supra. Point of error eighteen is overruled.

In his thirteenth point of error, appellant argues that the trial court denied him the effective assistance of counsel during his motion for new trial when it granted the State's motion to quash his subpoenas for jurors who had declined to answer defense counsel's post-trial questions relating to their service.

In his fourteenth point, he contends that the trial court denied him the effective assistance of counsel by issuing a blanket direction to jurors that they were under no obligation to answer any questions regarding their service.(12) More specifically, appellant asserts that his counsel was unable to render effective assistance in investigating statutory grounds for a new trial because the jurors had refused to speak with him. See Tex. R. App. P. 23.1 (grounds for a new trial in criminal cases).

A nearly identical argument was raised and rejected in Jackson v. State, 992 S.W.2d 469, 475-76 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999). In that case, we noted that "'[t]he refusal of any or all of the jurors, after their discharge, to talk to appellant's counsel or to sign affidavits relating to conduct in the jury room violates no statute and does not authorize reversal.'" Id. at 475 (quoting Phillips v. State, 511 S.W.2d 22, 30 (Tex. Crim. App. 1974)). We also noted that no error occurs when jurors are informed that they are under no obligation to talk to defense counsel. Id. at 31. We therefore concluded that the defendant in that case had no legal right to compel jurors to cooperate with defense counsel after they had rendered their verdict. Id.

Just as was the case in Jackson, in the instant case counsel had the right to pursue an investigation on appellant's behalf. Nothing prevented counsel from contacting the jurors and attempting to elicit information from them. However, nothing in the law obligated the jurors to cooperate with the defense investigation. See id. Appellant was not deprived of the effective assistance of counsel because he was not prevented from doing anything that he had the legal right to do. Id. at 475-476. Points of error thirteen and fourteen are overruled.

In his eighth point of error, appellant asserts that the mitigation special issue is unconstitutional because it omits a burden of proof. Art. 37.071 2(e). He asserts in his ninth point that the issue is constitutionally infirm because any meaningful appellate review of the jury's answer on the issue is impossible. In his tenth point, appellant asserts that the mitigation issue is unconstitutional when read in conjunction with Article 44.251, which requires a sufficiency review of the mitigation issue.

We have previously addressed and rejected all of these points. See McFarland, 928 S.W.2d at 498-99, 518-19; Lawton v. State, 913 S.W.2d 542, 556-558 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995); see also Jackson, 992 S.W.2d at 481. Appellant gives us no compelling reason to revisit these issues here. Points of error eight through ten are overruled.

In his eleventh point of error, appellant submits the "12-10" rule of Article 37.071 2(d)(2) and (f)(2) is unconstitutional. We have previously decided this contention contrary to appellant's position. Jackson, 992 S.W.2d at 481; McFarland, 928 S.W.2d at 519. Point of error eleven is overruled.

In related point of error twelve, appellant avers that the trial court erred in denying his requested charge informing the jury that he would receive a life sentence should they fail to agree on the answer to any one of the punishment issues. See Art. 37.071 2(a). Appellant alleges that this denial violated the Eighth Amendment. We have previously addressed and rejected this issue, and appellant has given us no reason to revisit it here. See Cantu, 939 S.W.2d at 644. Appellant's twelfth point of error is overruled.

Finding no reversible error, we affirm the judgment of the trial court.

*****

1. Unless otherwise indicated all future references to Articles refer to Code of Criminal Procedure.

2. The exact agreement is not confirmed in the record. However, there are occasional references by both parties to appellant having "unlimited peremptories."

3. Appellant does not argue that the procedure utilized by the trial court was non-constitutional error under any relevant statute. Instead, he asserts, through a detrimental reliance/estoppel-type-argument, that the trial judge's decision to return to the "old-fashioned" method of voir dire, after he had initially told counsel that he would provide him with unlimited strikes, amounted to constitutional error.

4. The trial court instructed the jury that it was "not to be swayed by mere sentiment, conjecture, sympathy, passion, prejudice, public opinion or public feeling in considering all of the evidence before you and in answering Special Issue No. 2."

5. In the instant case, appellant made no attempt to waive the mitigation issue at trial. In the absence of a timely request or objection, we will not decide the substantive issue of whether the mitigation issue is waivable. See Tex. R. App. P. 33.1(a)(1) (as a prerequisite to complaining on appeal, party must show that he made timely request, objection, or motion).

6. In his second point, appellant asserts that he was denied his federal constitutional rights. In his third point, he asserts he was denied his rights under the Texas Constitution.

7. Given his argument, we will assume appellant means "victim impact testimony/evidence" as opposed to just "victim testimony," which is arguably more all-encompassing.

8. During a home invasion, appellant allegedly shot Mr. and Mrs. Lee and their 22-month-old daughter.

9. In saying that the Lees' testimony was arguably objectionable, we are not deciding that the evidence was necessarily inadmissible. Instead, we only mean to suggest that, given the fact that the evidence was offered during the State's case-in-chief on punishment rather than as rebuttal to any defensive mitigation evidence, the testimony provided defense counsel with a ripe opportunity to litigate the issue. See, e.g., Mosley, 983 S.W.2d at 263 ("[W]e observe that victim impact evidence is relevant only insofar as it relates to the mitigation issue. Such evidence is patently irrelevant, for example, to a determination of future dangerousness").

10. Because a record focused on the conduct of trial counsel is not typically developed at trial, it is often difficult to review an effective assistance of counsel claim on direct appeal. Hence, these claims are usually better raised in an post-conviction application for a writ of habeas corpus. In such an instance, prior rejection of the claim on direct appeal will not bar relitigation of the claim to the extent that an applicant gathers and introduces evidence not contained in the direct appeal record. See Ex parte Torres, 943 S.W.2d 469, 475 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) and Jackson, 877 S.W.2d at 772 (Baird, J., concurring).

11. The record does show that defense counsel objected that Hanah Lee's statement was "nonresponsive," however, the objection was overruled and no other action was taken.

12. Consistent with this instruction, the State sent jurors a letter after trial reiterating that they could, but did not have to, discuss their jury service.

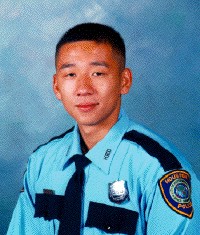

The victim

Officer Trinh was working at his parents' convenience store when a man walked in and attempted to rob him. Officer Trinh was shot in the head and died at the scene.