Appeal from the

United States District Court for the Northern

District of Texas.

Before KING, SMITH, and WIENER,

Circuit Judges.

WIENER, Circuit Judge.

In this petition for writ of

habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2241, 2254,

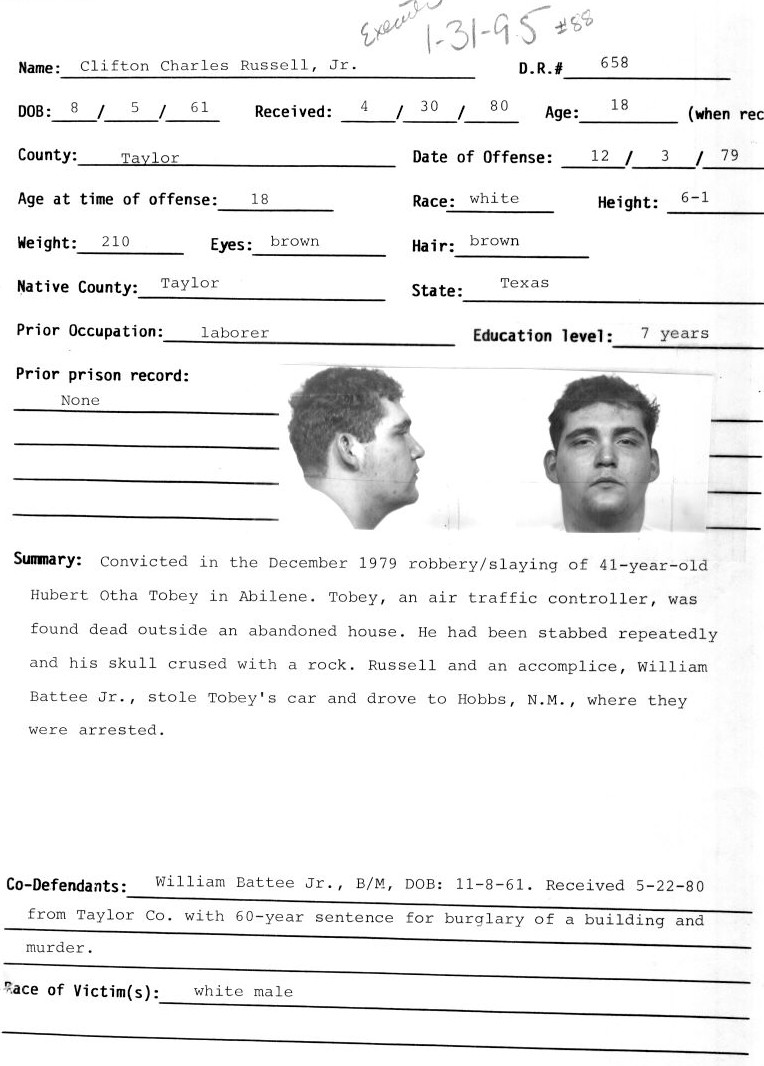

Petitioner-Appellant Clifton Charles Russell appeals

the district court's denial of his habeas petition.

On appeal, Russell challenges the constitutionality

of his sentencing proceeding which culminated in

imposition of the death penalty. After careful

consideration of the issues raised by Russell, we

discern no reversible error and affirm.

* FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS

Russell was convicted of the

capital murder of Hubert Otha Tobey, killed in the

course of a robbery. After Russell and a companion

robbed Tobey of his money and his automobile,

Russell struck him over the head with a large piece

of concrete and inflicted numerous knife wounds as

well, including one to the jugular vein. Russell and

two other men, Michael Wicker and William Battee,

Jr. subsequently were arrested outside a mall for

public intoxication.

Police traced the car and

connected it to Tobey, whose body had been

discovered by then. The police then seized Battee's

tennis shoes and Russell's pants, underwear, shirt,

and shoes, all of which had blood on them. The car's

interior also contained blood stains.

Russell was tried and convicted

for capital murder. During the sentencing phase of

the trial, the state introduced evidence regarding

Russell's poor reputation in the community, his

tendency towards violence making him dangerous to

society, and opinion testimony suggesting that he

was not a likely candidate for rehabilitation.

In response, Russell presented

five witnesses, four of whom were members of various

church organizations that opposed the death penalty

per se. In addition, Russell's mother, Jo Ann Lacy,

testified to Russell's troubled childhood and

incidents of violence against him. Specifically, she

recounted an incident during which Russell's

stepfather beat him severely with a baseball bat in

response to Russell's allegations that the shooting

of his mother nine months earlier by his stepfather

had not been accidental.

Russell required surgery to mend

his broken facial bones. Mrs. Lacy also testified

that Russell did not meet his biological father

until he was seven and never had a real father

figure. Finally, she stated that Russell had

suffered as a child because of his mixed racial

parentage.

Despite the testimony of Mrs.

Lacy, the jury affirmatively answered the first two

special issues submitted pursuant to Texas law:

whether the defendant acted deliberately, and

whether he posed a future danger to the community.

Accordingly, the judge sentenced Russell to death.

Russell's conviction and sentence were automatically

appealed to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals,

which affirmed the conviction and sentence, 665 S.W.2d

771.

Russell next pursued his state

habeas remedy, which was denied. Finally, Russell

filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the

United States District Court for the Northern

District of Texas and received an evidentiary

hearing. Russell's proceedings were stayed, however,

pending the Supreme Court's consideration of Penry

v. Lynaugh.

This stay was eventually lifted and the magistrate

judge entered his findings, conclusions, and

recommendation, followed by supplemental findings.

The district court adopted the report, dismissing

the petition and withdrawing the stay of execution.

Russell timely appealed.

II

ANALYSIS

A. Standard of Review

"In considering a federal habeas

corpus petition presented by a petitioner in state

custody, federal courts must accord a presumption of

correctness to any state court factual findings....

We review the district court's findings of fact for

clear error, but decide any issues of law de novo."

Evaluation of a petitioner's constitutional

challenge to the Texas special issues as applied to

him is, of course, an issue of law.

B. Penry Claim

In his first challenge to the

sentencing proceedings, Russell relies on the

Supreme Court's decision in Penry. In that case, the

Court ruled that the Texas special interrogatories

did not allow the jury to consider relevant

mitigating evidence of mental retardation and

childhood abuse and therefore failed to give an

"individual assessment of the appropriateness of the

death penalty."

Penry, Russell claims, dictates that the district

court erred in not granting a special instruction

for his mitigating evidence of his youth and

troubled childhood.

The state insists, to the

contrary, that Russell's claim must fail because

Penry clearly states that a special instruction is

required "upon request." Yet, the state urges,

Russell never sought a special instruction, and

therefore he cannot now complain of the district

court's error.

This argument ignores our holding

in Mayo v. Lynaugh,

in which we explained that Penry provides little

support for the proposition that a defendant must

contemporaneously object to or request additional

jury instructions.

"Although the Court's description of the rule sought

by Penry involved the request for jury instructions,

discussion of the important limitations to the

holding left unmentioned the role of the objections

or requests for instructions, and several statements

of the holding likewise omitted any such

qualification."

The opinion in Mayo also noted,

however, that this did not preclude the failure to

object or request additional instructions from

operating as a procedural bar under state law.

Since the decision in Mayo, however, we have

certified to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals the

question "whether [a] petitioner['s] ... claim under

Penry v. Lynaugh ... is presently procedurally

barred under Texas law."

The court answered the question

in the negative, holding that failure to object

contemporaneously in pre-Penry cases does not create

a state procedural bar as the decision in Penry " 'constituted

a substantial change in the law ... and there being

abundant Texas precedent demonstrating that the

holding amounts to a right not previously recognized.'

"

In any event, the state does not

argue that Russell's claim is procedurally barred

under state law, but insists that it is barred under

Penry, which the state interprets erroneously as

requiring a request for instructions. Based on Mayo,

we reject the government's claim that Penry imposes

a procedural bar when a pre-Penry defendant fails to

request a specialized instruction.

As Russell is not procedurally

barred from asserting the alleged error, we proceed

to the merits of his Penry claim. In that case, the

Supreme Court reiterated its holding in Jurek v.

Texas,

that the constitutionality of the Texas statute "turns

on whether the enumerated questions allow

consideration of particularized mitigating factors."

Consideration of relevant mitigating evidence is

required because " 'the sentence imposed at the

penalty stage should reflect a reasoned moral

response to the defendant's background, character,

and crime.' "

Therefore, the sentencer must "make

an individualized assessment of the appropriateness

of the death penalty" and treat the defendant as a "

'uniquely individual human bein[g].' "

In making this individualized assessment, the

sentencer must consider evidence about the

defendant's background and character " 'because of

the belief, long held by this society, that

defendants who commit criminal acts that are

attributable to a disadvantaged background, or to

emotional and mental problems, may be less culpable

than defendants who have no such excuse.' "

Penry stands apart from the cases

that preceded

and followed it

because of its ultimate conclusion: the Texas

special issues did not give effect to petitioner's

compelling evidence of mental retardation and abused

childhood that mitigated his moral culpability for

his crime. Penry did not invalidate the Texas

sentencing scheme, and subsequent Supreme Court

cases have refused to extend Penry to cover less

serious mitigating evidence.

Russell points to three types of

mitigating evidence in support of his Penry claim:

(1) his youth (he was age 18 at the time of the

homicide); (2) his troubled childhood; and (3) a

beating he suffered in his late teens at the hands

of his stepfather. We address each type of evidence

in turn.

1. In Johnson v. Texas,

the Supreme Court made clear that the mitigating

factor of a defendant's age is within the "effective

reach" of the second special issue. Thus, such

evidence is not problematic under Penry.

2. Russell's argument that his

jury was unable to give proper mitigating weight to

evidence of his troubled childhood is barred under

the non-retroactivity doctrine announced by the

Supreme Court in Teague v. Lane.

In Graham v. Collins,

the Supreme Court was presented with an essentially

identical claim raised by a habeas petitioner--a

Penry-type claim based on evidence of a non-abusive

but turbulent childhood--and held that the

petitioner's claim proposed a "new rule" under

Teague.

Russell has presented no evidence that his troubled

childhood rose to the required level of abusiveness.

3. The final type of evidence

that Russell offered during the punishment phase

described a single episode of violence--a severe

beating in the face with a baseball bat by a

stepfather who then attempted unsuccessfully to

shoot Russell. Both incidents occurred on the same

day when Russell was in his late teens.

Russell attempts to characterize this occurrence as

"child abuse" similar to the type introduced by the

capital defendant in Penry. We disagree.

Russell's beating occurred when

he was in his late teens, possibly when he was

legally an adult. But child-abuse, as it is

generally understood, occurs when a juvenile is of

such tender years that a violent beating--or, more

commonly, repeated beatings--by an adult would have

the tendency to affect the child's moral capacity by

predisposing him or her toward committing violence.

As the evidence here is significantly

distinguishable from that offered in Penry, the

Supreme Court's holding in Penry regarding

mitigating evidence of child abuse is not implicated.

More to the point, whether

evidence of the violence inflicted on Russell by his

stepfather was in the "effective reach" of jurors

under the special issues is not relevant;

the Eighth Amendment is not implicated in the first

place. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that

there are three basic categories of constitutionally

relevant mitigating evidence--that which is relevant

to a defendant's "background," "character," or the "circumstances

of the crime."

Russell's evidence of the violence inflicted by his

father does not fall under any one of these three

rubrics. Russell necessarily argues that his

evidence falls under the "background" rubric. We

disagree.

Under precedent in this circuit,

evidence of a defendant's background is

constitutionally relevant mitigating evidence only

if the crime committed by the defendant is in some

sense "attributable" to that background.

While "attribution" does not require a precise nexus

between such background evidence and the crime, at a

minimum the evidence must permit a rational jury to

"infer that the crime is attributable," at least in

part, to the defendant's background.

Albeit a close call, the evidence

of the isolated episode of violence inflicted by

Russell's stepfather does not permit such an

inference. As noted, that incident did not occur

during Russell's youth and was not indicative of a

pattern or history of child abuse--at least

according to the evidence offered during the

punishment phase of Russell's trial.

Neither did Russell offer any

evidence that the act of violence left him mentally

or emotionally impaired in a manner that would

permit a rational jury to infer that this single

incident somehow made Russell more predisposed to

commit a murder.

While, as a general proposition, a rational jury may

infer that child abuse renders one less morally

culpable for a violent crime,

the same cannot be said for a single episode of

physical abuse inflicted upon an adult. Thus, we

reject Russell's Penry claim predicated on this

evidence.

In sum, we conclude that there

was no Eighth Amendment violation in this case.

First, Russell's age at the time of the crime was

cognizable under the second special issue. Second,

his Penry-type claim based on mitigating evidence of

a troubled childhood is barred under the Teague

doctrine. Finally, evidence of a single episode of

severe violence inflicted by an adult on an adult,

without more, does not qualify as constitutionally

relevant mitigating evidence.

C. Undefined use of "deliberately"

Russell again relies on Penry to

make his argument that the state court erred by not

defining the word "deliberately" in the first

special issue, which asks whether the defendant so

acted. Russell recites the Court's reasoning that,

[a]ssuming ... that the jurors in

this case understood "deliberately" to mean

something more than that Penry was guilty of "intentionally"

committing murder, those jurors may still have been

unable to give effect to Penry's mitigating evidence

in answering the first special issue.

This quotation from Penry,

however, rests on the understanding that the

defendant had introduced mitigating evidence beyond

the scope of the special issues. In the instant

case, however, we have concluded that Russell did

not present any mitigating evidence that was outside

of the scope of the first special issue. Thus, the

quoted language from Penry does not advance his

claim.

D. Exclusion of Juror

Russell next asserts that the

district court erred in applying a presumption of

correctness to the state court's finding that

prospective juror Norman B. Scott was properly

excluded from the jury. The transcript of the voir

dire examination of Scott, reproduced in its

entirety in Ex Parte Russell,

demonstrates that Scott strongly opposed the death

penalty, that he "did not believe in" the death

penalty, and that he "could take the law and the

evidence, but when it come to imposing the death

penalty, I don't think I could do it."

When asked whether there were any circumstances

under which he could assign the death penalty, he

replied possibly so if the murder victim was a small

child, but he was not certain.

Applying the test set forth in

Witherspoon v. Illinois,

as clarified in Adams v. Texas

and Wainwright v. Witt,

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals held that Scott

had properly been discharged for cause as his

testimony indicated that "his views on the death

penalty would have prevented or substantially

impaired [his] performance as [a] juror[ ] in

accordance with [the] instructions."

The Court of Criminal Appeals' factual finding of

juror bias is entitled to a presumption of

correctness under 28 U.S.C. 2254(d), and we find no

reason why this presumption should not apply.

E. Eighth Amendment

Russell's final assertion attacks

the constitutional sufficiency of the evidence at

the guilt-innocence stage of trial. He insists that

there was no evidence to prove whether the murder

was committed by him or by his co-defendant Battee (who

received a sixty year sentence following a guilty

plea), or by both of them acting together. Absent

this evidence, he insists, imposition of the death

penalty violates his due process rights and the

Eighth Amendment's proscription against cruel and

unusual punishment.

In addition, he argues that the

disparity between his death sentence and Battee's

sentence of sixty years for the same offense is "an

invidious discrimination" in violation of the Equal

Protection Clause and violates the Eighth Amendment

as a disproportionate sentence.

Enmund v. Florida

construed the Eighth Amendment as prohibiting the

imposition of the death penalty against "one who

neither took life, attempted to take life, nor

intended to take life."

Thus, it is impermissible to sentence a person to

death solely on the basis of the acts of an

accomplice; there must be evidence from which a jury

could determine the petitioner's individual

culpability.

The state insists that the first

special instruction, which asks "whether the conduct

of the defendant that caused the death of the

deceased was committed deliberately and with the

reasonable expectation that the death of the

deceased or another would result" allowed the jury

to judge the evidence submitted against Russell.

The evidence submitted to the

jury included Russell's possession of the car and

the presence of a large amount of blood (compatible

with the victim's) on Russell's clothing, consistent

with someone who had brutally stabbed and beaten

another. In contrast, the state notes that Battee

had blood only on his shoes. Moreover, the state

emphasizes that, in Russell's trial, it did not

focus on Battee's intent to commit the crime, but on

Russell's. Thus, the state concludes, a reasonable

jury could have inferred Russell's individual

culpability for the murder; and the jury here had

the opportunity to consider that question under the

first special issue. We agree.

In Jones v. Thigpen,

we remanded for resentencing a case in which the

only evidence was involvement in the robbery and

blood splattered shoes. In the instant case, however,

there are two important distinctions. First, the

jury was properly instructed to consider the

individual culpability of the defendant sentenced to

death.

Second, the evidence--particularly the fact that

Russell's clothes (including his underwear) were

soaked with blood--is very probative, as it is

consistent with his inflicting the knife wounds

himself. Consequently, we agree with the state's

argument that the jury had the opportunity to

consider Russell's individual involvement in the

crime and, based on the evidence, reasonably could

have determined his guilt.

Finally, we address Russell's

claims involving the disparity of sentences, which

are especially common when one defendant pleads

guilty pursuant to a plea bargain and another

defendant is tried by jury. It is well established

that a prosecutor has discretion to enter into plea

bargains with some defendants and not with others.

Absent a showing of vindictiveness or use of an

arbitrary standard--neither of which Russell

demonstrates--the prosecutor's decision is not

subject to constitutional scrutiny.

III

CONCLUSION

In this petition for a writ of

habeas corpus, Russell challenges the imposition of

the death penalty without a Penry-type instruction.

As he fails to demonstrate mitigating evidence

outside the scope of the special issues, he does not

qualify for the additional instruction. Consequently,

his second claim--that the absence of a jury

instruction defining the word "deliberately" in the

first special issue precluded the jury from

considering his mitigating evidence--must also fail.

We reject Russell's challenge to

the exclusion of a potential juror on voir dire for

his views on the death penalty. Affording a

presumption of correctness to the state court's

finding that this exclusion was correct, we discern

no reason why this presumption should not preclude

Russell's claim. Finally, we hold that the jury

properly considered Russell's own individual

culpability for the murder, permissibly inferring

his guilt from the evidence presented, and we reject

his claim that the disparity in the sentences

imposed on him and on his accomplice violated the

Due Process Clause, the Equal Protection Clause, or

the Eighth Amendment.

For the foregoing reasons, the

decision of the district court in refusing to grant

the writ of habeas corpus is

AFFIRMED.

*****