Hostages safe; fugitive killed

4-day siege ends as adults flee their sleeping captor; Police raid home, shoot Palczynski, rescue boy hostage; Window escape stuns police

By Dan Thanh Dang and Nancy Youssef - The Sun

March 21, 2000

Two of the three hostages escaped out a window while Palczynski slept on a family room couch shortly before the SWAT team broke into the house. The third, a 12-year-old boy who was sleeping on the kitchen floor, was later led to safety by police.

The escapes "prompted us to go in or that boy was dead," said Police Chief Terrence B. Sheridan.

No officers were injured.

The events ended a 97-hour standoff that began when Palczynski, 31, shot his way into the apartment. He had been on the run since March 7, when, police say, he abducted his former girlfriend, Tracy Whitehead, and fatally shot the couple she was living with and a neighbor who tried to come to her aid.

A day later, he allegedly shot and killed a passing motorist in an attempted carjacking.

Lynn Whitehead, Tracy Whitehead's mother, jumped out the front window of the first-floor apartment in the 7500 block of Lange St. about 10:20 p.m. and her boyfriend, Andy McCord, followed about 20 minutes later. SWAT team members broke through a window and shot Palczynski, who had a gun on his lap under a blanket on the couch. They then escorted 12-year-old Bradley McCord -- Andy and Lynn's son -- out of the apartment.

"They have Joe. They have Joe," neighbors screamed shortly after the operation was over.

"I am here to report that we had a successful operation," Sheridan told a crowd of reporters at the command center in Dundalk as residents and police officers hugged each other. "Three hostages are safe because we had a successful operation."

Responding to angry criticism that police were slow to resolve the situation, Sheridan said, "Patience is what counted."

"Notwithstanding some of the criticism and the impatience, we had to stay focused," said County Executive C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger. "In my opinion, [Palczynski] felt he was the star of the show. He loved this. This was his show, this was his game.

"We're blessed. We're happy. And frankly, we're a little lucky."

Thankful family members praised God yesterday for answering their prayers over the ordeal.

"I had a feeling Lynn would do something," said Jean Jones, 47, who called her cousin "a fighter. She just probably had enough of it."

Jones rushed to the scene when she heard of the escape and ran to embrace her sister, Debbie Hands, 48, of Armistead Gardens, who said, "I thought he would kill them."

Lynn Whitehead's son, Bobby, 14, said: "We drove here as fast as we could. We are just so relieved."

Earlier yesterday, police had speculated about the condition of one of the hostages believed injured by a gunshot in the apartment Monday.

Last night, police said Palczynski said one of the hostages had been shot, but that proved to be false.

Neighbors had said that Palczynski had placed the younger McCord in front of an apartment window on more than one occasion. A source close to the investigation confirmed that people in the house had been used as shields.

Police also had tightened security and made two arrests in a restricted four-block zone circling the Lange Street rowhouse where the hostages were being held.

As the standoff dragged on, police negotiators continued talking with the suspected killer in "on-again, off-again conversations."

On the two previous days, Palczynski had fired out an apartment window at least nine times, once flattening tires on a police armored personnel carrier.

But it was one gunshot inside the house about 3 p.m. Monday that worried police. The shot was fired after negotiations between police and Palczynski resumed after six hours of silence.

A Whitehead cousin, Judy Gronke, told the Associated Press that Andy McCord's leg was grazed by the bullet. However, police spokeswoman Vickie Warehime said this morning no hostage was wounded in any way.

Yesterday, with a heavy rain falling, there were few bystanders at the scene. Police had become increasingly concerned about people congregating in the area, including those seeking to take advantage of free media attention. Some had tried to pose as reporters.

Police arrested Charles Ryan of the 7300 block of Berkshire Road and charged him with disorderly conduct and trespassing at the Berkshire Elementary School shelter about 1:30 a.m. yesterday. Police said Ryan, who was released on his own recognizance, was arguing and trying to cross into the restricted zone near Lange Street.

A second man, who police said identified himself as a free-lance photographer, was arrested about 1:30 a.m. at Dalton and Berkshire avenues when officers found him in the so-called "kill zone." The man was told to leave, police said, but a short time later was found in an alley behind the rowhouse where the hostages were being held with a camera and a picture of Palczynski in his wallet. Police said the suspect was to be charged last night. He was not identified.

A third person was taken into custody about 4:30 a.m. yesterday. The man, who described himself as a former producer for a local television station, was dressed in shorts and camouflage on a 30-degree night and his face was smeared with syrup, police said.

The man was taken into custody for psychiatric evaluation. Police said the man voiced "a plan to end this."

At one point before the escape, as reporters pressed him on reports that the hostage-taking had taken an inordinate toll on the neighborhood, police spokesman Bill Toohey answered heatedly: "Let us try to remember something. We believe this man has killed four people and kidnapped two. He's unpredictable. He's violent. He has three captives in there now.

"Let's not lose track of what started this. This is a man we think has murdered four people then traveled out of state and come back. Let's remember what happened the night of March 7, when he went into an apartment, dragged one woman out of there and shot two people and then a third and a fourth.

"Let's not lose sight of that."

Palczynski has been on the run since March 7, when police say he abducted Tracy Whitehead. She was staying with 50-year-old Gloria Jean Shenk and her husband, George Shenk, 49, after her most recent breakup with Palczynski.

Police said that as Palczynski dragged Whitehead from the Town & Country Bowleys Quarters Apartments, he fatally shot the Shenks and David M. Meyers, a neighbor who tried to help. Whitehead escaped the next night.

Police also allege that Palczynski shot and killed Jennifer McDonel, 37, a passing motorist, during an attempted carjacking the next night.

Palczynski then traveled, probably by train, to Virginia and stole two guns and cash from a house, said police, who also believe he forced a man at gunpoint to drive him back to eastern Baltimore County.

After eluding a massive manhunt in the woods and marshes of eastern Baltimore County, Palczynski reappeared Friday night, police said, when he shot at the Lange Street rowhouse and took the three hostages.

Yesterday, police faced criticism from angry residents who could not get pets out of homes in the restricted zone.

Police responded by removing three dogs from homes in the morning, Toohey said, but "at certain locations, there are people we cannot get out, and at certain locations, there are pets we cannot get out."

Toohey verified that police shot and killed a dog in a home where police had set up surveillance early in the standoff. He said the dog was shot because "it was in a threatening position."

Sun staff writers Jay Apperson, Tim Craig and Michael James contributed to this article.

A tragic trail of violence

The rampage that ended in Joseph Palczynski's death was inevitable, say the women who survived his abuse. He died the way he lived.

Long before the murderous rampage, long before the saga of fugitive love and violence, long before the hostages on Lange Street, Joe Palcyznski was known as a ladies' man.

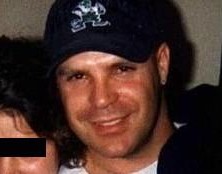

He had GQ looks, a buff body, an expensive sports car, money to burn and a questionable past that clung to him like heady cologne. He was a "bad boy," the type that always seems to attract women, particularly young ones.

Imagine being a high school girl of 16, maybe 17. How can you not be flattered by the attentions of this handsome guy who makes time to pick you up from school in his Nissan 300 ZX? He shows you an album filled with photographs of more than a dozen girls he's known -- young, slim, glossy-haired, smiling. It's clear he can have any woman he wants.

Instead, he chooses you. And it takes your breath away.

In the beginning, dating "Joby" is like starring in a romantic movie. He's 5-foot-8, 175 pounds of martial arts muscle, with sandy-brown hair and hazel eyes. Endlessly polite. Clean-cut, almost preppie; even his jeans are pressed. He has a job as a lifeguard and friends who jump whenever he snaps his fingers. You know he's calling when your pager flashes the number of his hero: 007.

On your first date, he takes you to meet his mom, Miss Pat, who is real pretty and couldn't be nicer. Anyone her son loves, she says, she loves, too.

Joby has seen a few things you'd rather not know about. So you don't listen much when he talks about making hit lists, buying weapons, being locked up. You believe people can change.

You really tune it out when he blames those other girls for getting him in trouble. You know you're nothing like them.

He phones constantly. He buys you flowers and gifts. Takes you horseback riding, arranges picnic lunches in the park. You go out on his Jet Skis, drive around like royalty.

He tells you how beautiful you are, how special. He says he's going to be with you forever -- no matter what.

It seems too good to be true.

It is.

The power of fear

On March 21, 2000, when police fired 27 bullets into Joseph C. Palczynski,his life reached the violent ending he had long predicted. In his last days, the 31-year-old man had followed through on a persistent threat -- to harm the family of any girlfriend who dared leave him -- and killed those who got in his way.

Over a span of 13 years, he had lured at least seven young women into a fantasy relationship. And one by one, each had discovered the truth of Joby's dangerously controlling personality.

Amie was 16 when he beat her and held her captive in 1987.

Kimberly was 16 when he blackened her eye, knocked her to her knees and threatened her with a razor blade in 1988.

Sharon was 17 when he attacked her at her school and threatened "to blow her brains out" in 1991.

A Gooding, Idaho, girl was 15 when Joby assaulted her in 1992.

Michella was 17 when he choked her and slammed her head against the shower tiles on Christmas Day 1995.

Stacy had just turned 17 when Joe grabbed her by the neck, shoved her against a wall and threatened to throw her off a balcony in 1996.

Tracy Whitehead, the last of his girlfriends, was also the oldest. She was 20 when she met him. She was 22 when he murdered the couple sheltering her, then kidnapped and terrorized her.

Joe Palczynski's story began to unfold publicly on March 7. For two weeks, it held the citizens of Baltimore -- and many beyond -- spellbound in horror. But the unknown tale -- the lengthy pattern of domestic abuse preceding Palczynski's rampage -- is chilling as well. The women who shared their stories with The Sun hope that their painful experiences can serve as cautionary tales, demonstrating how difficult it is to stop domestic violence.

"The scary thing," says Stephen E. Bailey, assistant state's attorney of Baltimore County and a prosecutor who faced Palczynski in court, "is that the system worked fairly well."

To the former victims and their families, there was never a question of whether Joby would eventually kill someone. The only question was when.

These young women did exactly what they were supposed to: They left their abuser, sought protective orders or filed charges. And each time, their actions put them at even greater risk.

When he was no longer able to use the power of love to control them, Joby turned to fear. He knew how to cultivate his "badness," to make it a source of influence. He kept his body looking like the lethal weapon he claimed it was, boasted loudly about his dark past and often predicted he would "die by the bullet." Joby believed he could make a girlfriend come back to him -- or drop charges -- if she was terrified by what would happen if she didn't.

Often he threatened to kill the girl's parents and leave her alive to suffer.

Joby liked people to be afraid of him, thrived on it, says George Coleman, who became a close friend when he was 14 and Joby was a high school senior.

Joby's male friends were almost always younger than he and easily impressed by cars and weapons. In that circle, toughness equaled status, and guns added to the equation. When Coleman first knew him, Joby had a rifle and a Magnum handgun. He played Russian roulette. He never possessed a high regard for life, Coleman says, and wanted to make sure everyone knew it.

Fear controls people, Joby told his last girlfriend. And when it didn't, when the young women persisted with their charges, Joby benefited from powerful cultural stereotypes about domestic violence and its victims: It's her word against his ... That's their private business ... He's always been so polite and well-mannered ... She doesn't look beat up to me ... She must have done something to provoke him.

In one sense, their collective efforts did work: Joby went to jail twice.

But when he was released, there was always another girlfriend, another victim.

And with each soured relationship and each trip to court, Joby grew more afraid of returning to jail. He would do whatever it took to force his victims to drop their charges. At one point, he masterminded a campaign of intimidation from inside the Baltimore County Detention Center.

For Joby, the stakes reached their highest in March, when Tracy Whitehead had him arrested for beating her. Another assault conviction would violate his probation and send him to jail for 10 years.

In the past, Palczynski's lawyers had claimed that mental illness was to blame for his actions. He was treated at mental health facilities almost a dozen times between the ages of 15 and 28. He had gone in and out of therapy, on and off medication. His diagnoses changed -- and were often contradictory. He was identified as hysterical, as depressed, as paranoid schizophrenic, as bipolar and as having personality disorders.

To some his behavior read like the textbook description of a chronic domestic abuser: manipulative, controlling, possessive, intimidating, physically violent. Ordered by the courts to attend a program for perpetrators of domestic violence, he was expelled because of his constantly disruptive behavior.

When it came to rehabilitation, he tried just about everything the criminal justice system had to offer.

But nothing, ultimately, could save George and Gloria Shenk, Jennifer McDonnel and David Meyers from Joby's most desperate hours. The four died in March during Joby's frenzied attempt to keep Tracy Whitehead from leaving him.

At that point, Joby felt he had nothing to lose.

"I can't live no more," he told his mother the day before he kidnapped his girlfriend. "I'm going to have to die."

Two faces of terror

Amie Gearhart was 15 when Joby surprised her with balloons on Valentine's Day. He wrote in her 1987 yearbook that he was wrapped around her little finger and loving it.

They met at Perry Hall High School: Palcyznski, the handsome senior, had rescued her from sophomore obscurity and a claustrophobic home life. Joby's old-fashioned politeness had even convinced Amie's parents that she was old enough for a "car date" in his shiny Mustang. That June, Joby took her to his senior prom. She wore a lacy pink dress; he sported a white tuxedo.

But the picture was far from perfect. During their five-month courtship, Amie had discovered another side to her boyfriend. Joby kept guns stashed under his bed and in his car. And once, he had held a knife to her throat.

He told her had two personalities: Joby No. 1 was calm and rational and Joby No. 2 was angry and strange.

But nothing could have prepared Amie for the Joby she would encounter on July 24, 1987. Almost 13 years later, she and other witnesses can still recall the events of that night.

She was hanging out with a group of kids on a parking lot near the beach in Ocean City, eating ice cream from a pint container. Spending the week in a condo with a friend and her family, Amie didn't expect to see Joby. But about the time she fed a bite of ice cream to another guy, she spotted her boyfriend coming toward her.

Without explanation, Joby knocked Amie to the ground. As friends tried to intervene, he began to kick and beat her.

When police arrived, he squeezed Amie's hand hard and whispered: Don't tell them nothing!

Stunned, she obeyed.

Meanwhile, Joby calmly told the officers he was looking for his watch and ring, which he had lost in the parking lot. After the police left, he walked Amie toward the ocean and ordered her friend's 14-year-old brother, Jason Whitekettle, to join them. I need a witness, he said.

On the beach, Joby forced the two teen-agers to hold hands and walk in front of him like prisoners, kicking and hitting them to keep them moving.

They walked to the Delaware line, at least half a mile, Joby screaming and blaming Amie for making him lose his ring, for ruining his life. He interrogated Jason and Amie about where the boys and girls slept in the condominium and who Amie had spent time with that week.

Finally he forced the two to sit on their hands, cross-legged on the sand, with their backs to a chain link fence while he paced back and forth, threatening to break their legs. He ordered Jason to hit Amie; when he refused, Joby grabbed Jason's hand and hit her in the chest with it three times.

At one point, Amie urged Jason, who was small and thin and no match for Joby, to run for help. He did. With Jason gone, Joby's rage found one focus. Choose your death, he told his girlfriend: drowning, choking or beating. Then he threatened to kill her family.

Amie pleaded with him, sobbing, as he pounded her chest, over and over, laughing. Then she spotted a group of men fishing at the water's edge and broke free. Grabbing their flashlight, she shone it on her face to show what her boyfriend had done.

It was the calm, reasonable Joby who caught up to her and reassured the fishermen: The couple would go up under the street light and talk things out. They didn't need to interfere.

In a daze, Amie went along with it. When Joby saw the extent of his handiwork, he began crying and apologizing, begging her to forgive him.

Later, X-rays and photographs taken at the medical clinic at 93rd Street showed Amie suffered contusions of the left eardrum -- she couldn't hear correctly for months -- lacerations and swelling of her cheek and nose, a contusion of the right eye that caused it to hemorrhage, and a bruised rib cage.

Although the teen-ager was reluctant to press charges, her mother insisted: Otherwise he'll keep on doing it. Amie's mother later recalled receiving a phone call from Joby's mother, who wanted them to drop their charges. Amie's mother refused. Your son's abusive, she told Pat Long. He's going to kill somebody someday.

That fall, Amie felt alarmed to see Joby with a 16-year-old named Kimberly. Soon, she sought out Amie for advice: Joby had given her a black eye, and she wanted to know how to get away from him.

Get a restraining order, Amie told her. Press charges. Because Kimberly -- and Joby's next victim, a 17-year-old named Sharon -- declined to be interviewed and were minors at the time of these events, their last names are being withheld. But their experiences with Joby are recounted in reports to police. Like Amie Gearhart, they came to know Joby No. 2.

From a charging document filed by Kimberly's mother: Oct. 18, 1987: "Joseph C. Palczynski searched through Kim's bedroom without permission when she was in the shower. While searching he found birth control pills. The discovery of these pills made Joseph very angry because he did not want her taking them. As a result, he began to slap Kim several times in the face with both an open hand and a back hand, resulting in a black eye [right] and bruising of the right and left cheekbones. After a series of slaps in the face, Joseph then punched Kim in the stomach, knocking her to her knees. He continued to threaten Kim, stating that if she didn't do what he said he would do it again."

Feb. 21, 1988: "Joseph pulled Kimberly into the bathroom at his house [owned by his grandmother] stating that he wanted to have sex with her. When she refused, he became very angry and very forceful. ... Joseph punched her with a closed fist causing multiple bruises along Kim's breastbone, then exited the bathroom ... went into a closet and got a razorblade. He then proceeded to threaten Kim saying 'If you don't come here and talk to me, I'll beat you some more whether my grandmom is here or not!' "

Palczynski was convicted of beating Kim and sentenced to two years of supervised probation. In January 1989, facing Amie Gearhart's charges, he pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. A psychiatrist found him competent to stand trial, and he was later sentenced to four years in prison in Hagerstown. He served two, including some time for an attempted escape. He received regular counseling there and was described as having "deliberately [sought] out dangerous situations consistent with a fantasy identity as a 'Rambo' like hero."

Palczynski was 22 when he was released from jail in April 1991. He returned home to live with his mother and stepfather, worked part-time at an athletic supply store, took lifeguard courses and occasionally did construction work. According to mental health reports, life at home was strained: His parents disapproved of his dating high school girls, whom he would sometimes sneak into the house.

By August, he had moved into an apartment with two roommates. He was dating a 17-year-old named Sharon when, in September, less than six months after his release from jail, he was warned by the assistant principal not to trespass on the grounds of her school. Later, he was arrested for attacking Sharon there.

From her charging document:

Nov. 8, 1991: "We were arguing in front of [her school]. I proceeded into [the school]; he came running after me. He pushed me up against the wall. I pleaded with him not to hit me but the next thing I knew I was on the ground screaming. He has also threatened my parents. (To kill them and leave me living to suffer.) He said if he goes to jail he will kill me or get someone to hurt me! He has gotten people to come to my house before. This is not the first time he has hurt me, but before he only pushed me and pulled me by my hair."

Out on bail, Joby was ordered to have no contact with Sharon. But he phoned her repeatedly, she complained, threatening "to blow her brains out" if she didn't drop her charges against him. He also purchased an Inland M-1 .30-caliber rifle from Edgewater Pawn Shop, telling his friend George Coleman, who thought he was "just talking big," that he was going to use it to shoot people at Sharon's school.

Meanwhile, Sharon filed additional charges describing the threatening phone calls. Palczynski was arrested and held at the Baltimore County Detention Center.

When staff there decided his behavior called for psychiatric evaluation, he was sent first to Franklin Square Hospital and then to Spring Grove State Hospital.

At Spring Grove, he was initially diagnosed as having bipolar mood disorder and possible depression. But on Dec. 16, 1991, two days after arriving at the facility, he escaped and fled the state with the identification cards of a friend.

A month later, the fugitive surfaced in Gooding, Idaho, when a woman filed a complaint against him for assaulting her 15-year-old daughter and threatening to kill the girl's brother. Neither of them could be found for interviews. But a police report and a newspaper article gave the following account of events: While Gooding police were investigating the mother's accusation, Maryland State Police alerted their counterparts in Idaho that Palczynski was believed to be hiding out in Gooding. The man was unstable, they were told, and possibly armed with an automatic rifle, a 9 mm handgun and a shotgun.

On the morning of Jan. 17, the fugitive barricaded himself alone in an apartment and told police negotiators he would kill himself and shoot people in a nearby parking lot if police advanced. After nearly 16 hours, a SWAT team hit the apartment with tear gas. Palczynski was apprehended and eventually returned to Maryland.

Things looked pretty grim: Less than a year after leaving jail, he now faced charges of violating federal gun laws, of battering and threatening Sharon and of escaping from Spring Grove Hospital. Any conviction could return him to prison.

Unless he was judged legally insane.

Clearly his mental state was to blame for his actions, his lawyers argued. Palczynski was sent to the Federal Correctional Institution in Petersburg, Va., for a month's evaluation. His stay there was to set the tone for the next three years, a time he spent navigating -- some believe manipulating -- the federal mental health system.

In the course of his evaluation, Palczynski told the federal psychologist that he had illegally purchased the gun at the pawn shop to kill the "ninjas" who were trying to kill him. When he cut his wrist twice, once deeply enough to require stitches, he told the psychologist a voice told him to do it.

Later, Palczynski would boast to girlfriends that he had cut himself to fool the system. If so, his ploy worked: The federal psychologist diagnosed him with schizophrenia, paranoid type, and concluded he met the criteria of legal insanity, a decision that led to his being found not guilty on federal weapons charges.

Fifteen months later, after court-ordered treatment at a number of government facilities, Palczynski appeared to have made a complete recovery. According to another psychologist, the 25-year-old man's condition was now "extremely stable" with "no evidence of bizarre behavior or verbalizations which might be indicative of delusional thinking." He had not taken medication for more than a year.

If the patient had indeed suffered from a major mental illness in 1992, he had fully recovered by September 1994, psychologist M.A. Conroy concluded. Her diagnosis: personality disorder, not otherwise specified, with antisocial and borderline features. She did not see any reason for further psychiatric treatment or follow-up.

Later, Joby's lawyer would speculate his client had "conned" the doctors into releasing him. Joby's mother would maintain that he had remained stable without medication only because he had been in a stress-free situation where no one provoked him.

In any event, the assessment brought him home. He no longer faced prosecution for beating Sharon because a judge had dismissed her charges. While he was institutionalized, his lawyer had argued successfully that his right to a speedy trial had been denied.

That same argument did not prevail with another judge, who reviewed his charges for escaping Spring Grove. In January 1995, Joby received a three-year suspended sentence with five years of probation.

He was free to choose his next victim.

Seeing beyond the surface

In the summer of 1995, 42-year-old Gary Osborne was growing concerned about his teen-age daughter. There was something about the guy Michella was dating that he didn't trust.

Joe Palczynski was a nice-looking man with a fancy sports car. He was as polite as they come and seemed devoted to Gary's 17-year-old daughter and her baby. But he had no actual job that Gary could see. And right from the start, Gary thought the guy was older than he let on.

He was controlling, too. Gary often would see Joby hiding in the bushes outside the Osbornes' house in Chase, peering into the windows to see if Michella was talking on the telephone or smoking the cigarettes he had forbidden her.

Then one day he saw bruises on Michella. It was all he needed to know.

Roughing up women pressed all his buttons: His ex-wife, Diane, had been beaten to death in 1989 by her boyfriend. Now, as Gary questioned Michella about Joby, father and daughter argued. It turned out Joby was 27, not 23 as he'd claimed. And the bruises? Michella tried to explain them to her father by saying she'd fallen off a ladder helping Joby's mother with her cleaning business. But Gary suspected Joby. One day in July, when Gary ordered Joby out of his house, a fight ensued. Gary, a slender 125 pounds, went to the hospital with four broken ribs and a split lip requiring stitches.

He didn't press charges -- he didn't want any more trouble. But he would change his mind after Joby beat his daughter on Christmas night.

In a recent interview, Michella gave this account:

She had spent the holiday with Joby, visiting his family as well as hers. At the end of the day, tired, she said she wanted to spend the night in her dad's house instead of Joby's apartment. Stung, he argued with her and things quickly got out of hand.

He choked her and slammed her head against the shower tiles. Michella scratched his face, staining with blood the white sweatshirt she had given him. Joby yelled that she had 10 minutes to remove the blood or he would give her the beating of her life.

Desperate, Michella soaked the sweatshirt in cold water, rubbed the stain with ice. It wasn't enough, though, and when the time was up, Joby made good on his threat.

After beating her, he ordered her to go into the kitchen and pick up a knife. Then, putting a cloth over his own hand, he took the knife from her. I could kill you right now, he threatened. My fingerprints ain't on it, yours are. All I have to do is tell the police you tried to kill me with this knife and I killed you in self-defense.

Later, his anger spent, Joby fell into bed exhausted. Michella lay beside him shivering, certain that he would kill her if she moved to get away.

The next morning, when he seemed calmer, Michella begged to go to work. She told him, over and over, how much she loved him, how she would never leave him, how she would never go to the cops. Then she reminded him she was the one with an income.

Joby drove her to the video store where she worked, then watched her from his car for a while. When he left, Michella took a cab to her father's house.

After Gary Osborne and his daughter went to police to report the incident, Joby's mother begged them to drop the charges. Joby, on probation for his 1991 escape from Spring Grove Hospital, would undoubtedly go back to jail if he were convicted.

But Gary refused to be swayed. It was a fateful decision.

Awaiting trial in the Baltimore County Detention Center, Joe Palczynski made a plan. He was determined to change Gary Osborne's mind. And he had friends who could help.

A jailhouse scheme

Joby rarely -- if ever -- dated just one girl, and he never lacked female friends. If one girlfriend filed assault charges against him, two or three other women were ready to testify that she had made up the whole thing: The Joby they knew would never do something like that.

In the fall of 1995, when things with Michella were strained, Joby struck up a friendship with a starry-eyed teen-ager from Pasadena. Lisa Andersen was 17, a junior at Chesapeake Senior High. He was 22 -- or so she thought.

"When I first met him he said, 'You have a beautiful smile.' I'd think, 'Whoa! I've never had anyone say that to me!' He was like, 'You've got gorgeous eyes and pretty hair.' He treated me with the utmost respect and dignity. ... He was something I had never experienced before."

Suddenly, though, Lisa's new love was whisked away to the Baltimore County Detention Center. He'd been taken there on false charges, he told her. Michella Osborne had been cheating on him, he explained, and when he found out, he pushed her. But that was all.

Lisa believed him and devoted herself to keeping up his spirits.

At first, Joby called collect every other day from jail. Then he began calling more often, in the morning, at midday and in the afternoon. Lisa began cutting school so she could spend the day talking to Joby. He was 007; she was 00 -- "his sidekick, partner in crime."

It wasn't long, Lisa says, before she dropped out of school and moved in with Ramona Contrino, a friend of Joby's. Contrino was using his 300 ZX while he was in jail and would often drive the teen-ager there to see him.

During those visits, Joby sometimes ridiculed Lisa's makeup or clothes. But then he'd apologize: I'm sorry, baby. She attributed his behavior to the stress of jail. It only made her want to help him even more.

Joby began his campaign to intimidate the Osbornes into dropping Michella's charges against him. He accused his former girlfriend of theft, identifying her as an adult on his charging document to get her locked up. The attempt failed. Then he filed charges against Gary Osborne over the fight the summer before, claiming Gary had threatened to "kill my family and blow my house up and cars."

Gary responded by filing charges against Joby for the same incident. Shortly afterward, he awoke one morning to discover his pickup truck vandalized. All four tires were flat. There were deep scratches in the paint on the driver's side, and 10 pounds of sugar had been poured into the gas tank.

When the Osbornes still did not drop their charges for the beating of Michella, Joby upped the ante. He asked Lisa Andersen to accuse Gary Osborne of threatening to blow up her house and kill her if she dared to testify on Joby's behalf.

Lisa was horrified. She wanted no part of it.

Leese, you're going to do it, and you're going to do it NOW, she recalls Joby yelling over the phone one afternoon. You have my car, and you're riding around in it. You do it now, or I'm gonna kill you. You have 15 minutes to go down there, pick up the papers and call me.

The teen-ager decided to pretend she had filed charges. Faking an official's signature on charging documents, she wrote down what he had told her and mailed it off to him.

Joby saw right through it.

"He said, 'Who do you think you're playing with? You lied to me! Do you think this is a game?' " Andersen recalls. "He said, 'If you don't do this, I'm going to kill your family.' "

On April 9, 1996, the 17-year-old drove Joby's car to district court to file charges against a man she had never met. As a minor, Andersen could not legally file charges by herself. But no one asked her for identification. Her charging document stated: "Sunday, March 31st 1996 at approx. 12:00 p.m. I received my first phone call from the Defendant Gary Osborne he said 'hey you little bitch go ahead and testify for Joe,' then I replied with 'Who's this' he responded with 'this is Gary Osborne, Michella's ------ father.' ... Later that afternoon I received another phone call ... and he said 'Go ahead and mess with my family Bitch. I'll ------ kill you, And blow up your ------ house so go ahead bitch and then it's all over for you.' "

Police arrested Gary Osborne on April 18. Charged with making bomb threats and obscene comments over the phone, he was handcuffed and driven to the Essex police station, where he stayed until his wife could post bail.

Three more times that month, he was arrested on similar charges filed by Ramona Contrino's sister, Carla. Each time, neighbors watched as he was handcuffed and taken away. Each time, the family had to raise the bail money. At one point, while being held in the Baltimore County Detention Center, Gary wore a badge alerting guards to keep him away from another prisoner: Joe Palczynski.

Michella pleaded with her father to let her drop the charges, but Gary Osborne held firm.

"Joby wanted Gary bad," Lisa Andersen recalls. "He wanted to make Gary's life a living hell. Gary was controlling Michella, but Joby wanted to control Michella. Joby couldn't handle it when somebody else was controlling something he considered his."

The false charges against Osborne were dismissed after Carla Contrino admitted she lied and tape-recorded a conversation that also implicated Lisa Andersen.

Later, Gary Osborne would sue them both. But in the summer of 1996, he had more to worry about than the money he had lost from missing work, posting bail and paying attorneys. His biggest worry was that Joby was free.

When prosecutor Steve Bailey decided against trying the case before a jury -- there were no reliable witnesses -- Joby pleaded guilty to the charges of battery and witness intimidation and received suspended sentences from Judge John G. Turnbull II.

The court put him on probation and ordered him to stay away from Michella Osborne and her family.

Gary Osborne cut down all the bushes around his house.

He didn't want any more surprises.

The lies add up

The first thing she noticed was the white 300 ZX. It was the summer of 1996, and 16-year-old Stacy Culotta was pumping gas into her car at the Royal Farm Store in Chase. The sports car that pulled up was a looker. So was the guy driving it.

I like the wheels on your car, the teen-ager said. The man introduced himself and told her he had a set of rims and tires that he was trying to sell. So Stacy went to Joe Palczynski's house to take a look. They exchanged phone numbers. Before long, he was courting Stacy, telling her everything she wanted to hear, making her feel grown up in a way no one else ever had.

On her 17th birthday, only two weeks after their first date, he showered her with gifts -- "expensive shirts from J.C. Penney's and Hecht's," Stacy recalls -- that she hid from her parents.

He just took her breath away, she told her friends. Joby, now 27, had recently received a suspended sentence for battering Michella Osborne, a girl who lived just a few blocks from the Culottas in Chase. He told Stacy he was 20, that he had "some bad stuff in his background."

People change, she figured. And anyway, she was head over heels.

Her parents were considerably less so. No way he was 20 with all those crow's feet, they told her. Why was he following her everywhere, making demands?

When they discovered he'd been in the county jail, Stacy had an explanation: A jealous girlfriend had lied, set him up. Her parents weren't buying it. They forbid her to see or even talk to Joe Palczynski.

So she sneaked around behind their backs. And Joby helped. He would pick her up in different cars so her parents wouldn't suspect anything; he persuaded friends to lie to the Culottas about where Stacy was.

One night, Stacy told her boyfriend that her father had found out some bad things about him.

"What does he know?" Joby asked, sounding unconcerned. "About the kidnapping? Assault weapons?" Her dad knew about three charges, Stacy said. He knew about assault, battery and kidnapping.

"Ho, ho, ho! I'll be lucky if that's what it is. Are you serious? Only that much?"

"Yeah."

"Hon, I got a record for real. In my entire life, I've, like, 40 charges. ... He didn't get no printout of my record. There's no way! ... I've had robbery, OK?"

"Uh-huh."

"I've got four, five, six assault and batteries," he continued matter-of-factly, as if checking off a grocery list. "Two or three counts of trespassing. Two counts of kidnapping. Three counts of false imprisonment, OK? Two counts of phone harassment. Two counts of intimidating state witness. One count of intimidating -- "

"Well, why did only three of them come up?"

"I have no idea! One count of illegal possession of firearms. One for fleeing and eluding. What else? Just all kind of sh--, hon, all kind of sh--. ... Now, as far as conviction: Three counts of assault and battery. ... We're going to move to a Phase Two. You got a tape recorder?"

The time had come, Joby told Stacy, to start taping her parents' phone conversations. He needed to find out how much they knew -- and what they planned to do about it.

"I'm going to find out your Dad's sources so he ain't pulling nothin' on me. He's gonna make me move to a Phase Three ..." Joby considered the possibilities: "He don't want me to do that. I'll know everything about him. I'll know where his mind's at ... I start putting him under surveillance." Joby was already watching Stacy constantly.

Possessive, he didn't want her to spend any time with friends. He often took her out of school just so he could be with her. And there was the rule about returning his calls: If he paged her, Stacy had better get in touch with him within two to three minutes or risk "severe consequences."

At times, she felt ambushed by his anger. Once Joby pulled a cigarette from her mouth, grabbed her by the neck and slammed her up against a wall. Another time, after a phone conversation in which Stacy said she didn't want to see him anymore, Joby tried to run her and a girlfriend off the road.

His mood shifts were sudden and unpredictable. Five minutes after slamming her against a wall, Joby would offer to make dinner. He'd prepare steak, mashed potatoes, corn on the cob, light the candles.

And Stacy would begin thinking, Maybe I shouldn't have said what I said to him; that's why he pushed me against the wall. Maybe he really is sorry. She was solidly under his thumb.

But she had the luck of good timing. After a months-long battle with the Osbornes, Joby wouldn't have welcomed the prospect of another hostile family pressing charges. And Stacy had very nosy parents.

Every day, Diane and Vince Culotta would drive out of their housing development and see Joby standing on the corner, waiting and watching. Neighbors reported that he was parking down the street and running up to their house to peer in the windows, sometimes several times a day. As the sister of a police officer, Diane had few qualms about taking Joby to court -- and she felt confident she recognized him for what he was: an abuser.

She would later give her daughter a book, "The Gift of Fear," which described classic signs of a batterer, and underlined traits she thought applied to Joby: bullying; verbal abuse; intimidation; talking about getting married, having kids and being together forever shortly after their first meeting; battering women in previous relationships; stalking; police encounters; using money to control people; believing others are out to get him; liking violent films; having a fascination with weapons; minimizing any kind of abusive behavior.

In August, Vince Culotta told Joby to stay away from his daughter. In September, he filed a petition to prevent him from having any contact with her. In November, the Culottas got lucky: Joby went to jail. His convictions in the Osborne case violated the terms of his probation on the 1991 Spring Grove escape charges.

Judge John Fader sentenced him to serve three years. "This man is dangerous," he said. "He is out there hurting people. I can't believe any human being can make so many mistakes and be given so many chances and not appreciate it, and I do not feel, from what I hear, that the mental state is anywhere near as much an excuse as he tries to use it for a crutch."

But Stacy still believed they belonged together.

From jail on the Eastern Shore, Joby told his mother to hand-deliver a letter to Stacy at work. Pat Long stood in the aisle of the Safeway while the teen-ager read it, then took it back. She had promised her son Stacy's parents wouldn't get their hands on it.

In the letter, Joby promised Stacy he would never let her go. No matter what, they would be together some day, he wrote. And Stacy knew she could wait for him. When Joby finished his jail term, they would marry and move to Florida.

She felt hopeful. Until an acquaintance showed her another letter, a letter she was never meant to see. In it, Joby described his relationship with Stacy as "a big joke." She was just "another one under my belt," he told the male friend to whom he had written.

"If you tell a girl what she wants to hear," he continued, "you could ---- all of them and that's what I was doing for the past 10 years. Oh it's not just what you tell them but how and where you tell them. The only hard part is remembering the lies. I'm sure you get the point. I added up all the girls I ------ and I ------ 142 girls and 38 of them were virgins!"

Devastated, furious, Stacy wrote Joby that it was over. She should have known better.

Strange cars began racing past her house. A guy in a green Mitsubishi, one of the cars Joby had borrowed to fool her parents, was waiting in the parking lot at night when she left work. Often, he followed her home.

She found notes on her windshield with cryptic messages and numbers meaningful only to her and Joby. She received hang-up phone calls.

Shortly after one of Joby's friends took her out to dinner to cheer her up, her new pager began receiving coded messages: "Watch your back, bitch" and "I'm coming back for you."

Diane Culotta wrote the victim notification services of the state's division of correction:

"How does he talk people into doing this crazy stuff? They follow her, leave notes, call our house, what else is next? I'm afraid to ask. ... He's a very strange, manipulative person ... I'm afraid if he's this obsessed about her now, what will it be like when he gets out of jail?"

Stacy's mom collected names, license tag numbers, dates, incidents and scraps of paper, amassing evidence of intimidation that would stand up well in court. She also wrote the parole board requesting to be informed before Joby's release: "I do not want to look up one day as I'm driving, as I have done several times before, and be startled to see him in my rear-view mirror."

She need not have worried. When Joe Palczynski was released from prison on June 20, 1998, Stacy joined the ranks of former girlfriends, her photo just another among many.

Soon, Joby had a new sports car, a Mazda RX7, and was romancing a young woman he had met in the check-out line at Super Fresh, 20-year-old Tracy Whitehead.