Stephen Ray

Nethery, Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

James A. Collins, Director, Texas Department of

Criminal Justice,

Institutional Division, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 92-1742

United States

Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit.

June 11, 1993

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc Denied July 21,

1993

Appeal from

the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Texas.

Before POLITZ, Chief Judge,

KING and BARKSDALE, Circuit Judges.

POLITZ, Chief Judge:

Stephen Ray Nethery was

convicted of capital murder and sentenced to

death by the Texas state court. With all direct

appeals and collateral state reviews exhausted

he seeks federal habeas relief. The district

court denied his application and refused to

grant a certificate of probable cause for

appeal. We granted CPC. For the reasons assigned,

we affirm.

Background

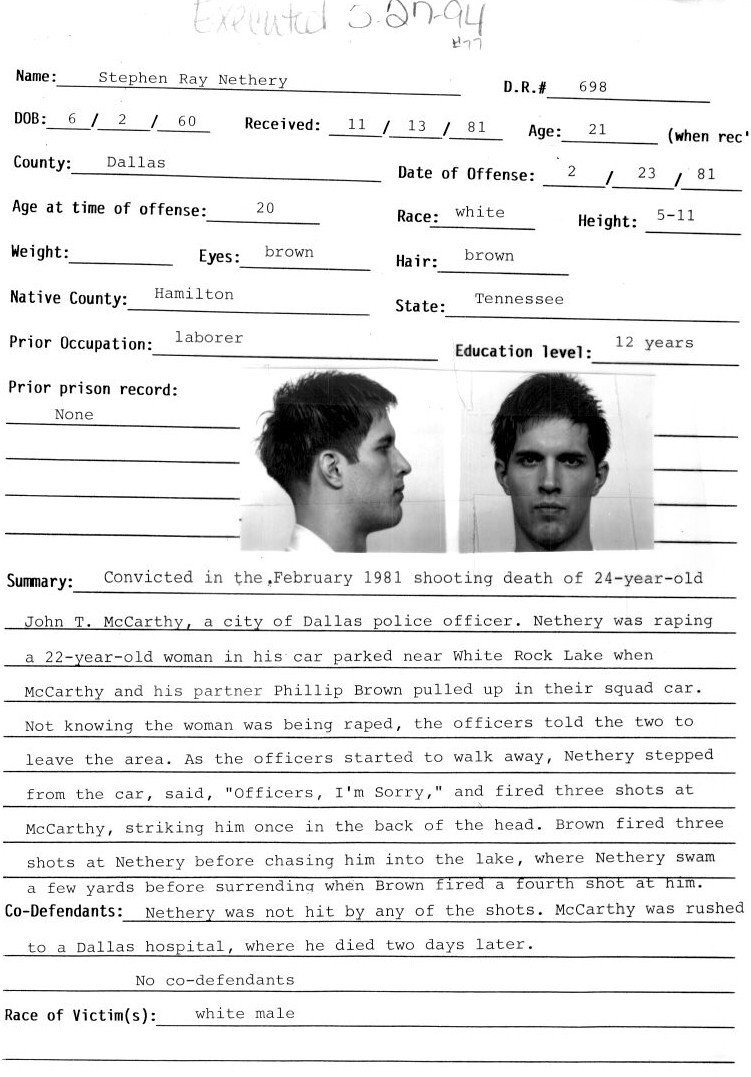

On the evening of February

22, 1981, Nethery met a woman in a Dallas bar.

They consumed several strong drinks and he

persuaded her to leave the bar with him to go to

a secluded spot to smoke marihuana. They drove

to an area near a lake in a high crime area and

parked. It was well after midnight. Nethery made

sexual advances which his companion initially

resisted. A pistol fell out of his pocket. He

caused her to disrobe. He did likewise and they

engaged in sexual relations over an extended

period.

A police car on patrol

spotted them and pulled up alongside. Two

officers exited their vehicle; Officer Phillip

Brown approached the Nethery auto and shined his

flashlight inside. Officer John McCarthy stood

by the police auto. As Officer Brown illuminated

the interior of Nethery's car the woman was

attempting to put on her clothes; Nethery was

naked. Officer Brown told them that they could

be arrested and instructed them to leave the

area.

At this point

Brown turned to return to the police cruiser. As

he did, Nethery exited his car, rested his arm

on the top of his vehicle, said "I'm sorry," and

fired three quick shots. He hit Officer McCarthy.

Officer Brown returned fire and Nethery ran

toward the lake. Brown pursued and chased

Nethery into the lake where Nethery finally

surrendered. Upon returning to the parked

vehicles, Brown found his patrol partner on the

ground, calling for help on his mobile radio.

Officer McCarthy was rushed to the hospital but

subsequently died of the gunshot wound to the

back of his head.

Nethery was indicted and

tried for capital murder in Dallas County.

Pursuant to Texas procedure,

the jury first determined his guilt and then

considered three statutorily mandated special

issues.

In response to these

questions, the jury found (1) that Nethery's

conduct was deliberate and undertaken with the

reasonable expectation of McCarthy's death; (2)

that there was a probability that Nethery would

commit further criminal acts that would

constitute a threat to society; and (3) that

Nethery's conduct was unreasonable in response

to any provocation by Officer McCarthy. Based on

these answers, Nethery was sentenced to death by

lethal injection.

Nethery's appeal to the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals was direct and

automatic. That court found no reversible error

in any of his 55 points of error.

The Supreme Court denied his petition for

certiorari, rendering his conviction final, in

early 1986.

Nethery next turned to the

writ of habeas corpus. The same judge who had

presided over his trial denied his first state

application and resentenced him to death.

Nethery maintains that at this point the judge

disclosed his close personal relationship with

Officer McCarthy. Nethery appealed the denial to

the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, adding a

claim of judicial bias. That court again denied

relief.

Nethery thereafter filed his

first application for a federal writ, which was

dismissed for failure to exhaust a claim. He did

nothing until his execution was rescheduled, at

which point he returned to the state district

court again seeking habeas relief. This time a

different judge was assigned to the case. The

court found no factual or legal basis for relief.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed.

Nethery then filed the

instant application for federal habeas. The

district court assigned the matter to a

magistrate judge who held an evidentiary hearing.

The magistrate judge found no credible evidence

supporting Nethery's claim of judicial bias and

recommended that the application be denied. The

district court adopted the recommendation and

denied an application for CPC. We granted CPC.

Analysis

I. JUDICIAL

BIAS

Nethery claims that his trial

was tainted by the presiding judge's failure to

disclose a close personal friendship with the

deceased officer. He contends that the

relationship did not become apparent until the

judge went into "an emotional tirade" during a

resentencing hearing on Nethery's application

for state habeas relief. The record of that

hearing indicates that the judge sentenced

Nethery to die on McCarthy's birthday and then

immediately called a short recess.

After returning, the judge

directed the clerk to send a copy of the death

warrant to Nethery so he could "study it" before

he died. Nethery claims the judge also professed

a close friendship to the victim, although the

record is silent in this respect. The state

contends that the judge simply was appalled by

the senseless killing.

The accused in any criminal

trial is guaranteed the right to an impartial

tribunal.

To secure relief on this basis, Nethery had to

establish that the judge was influenced by

interests apart from the administration of

justice and that this bias or prejudice resulted

in rulings based on other than facts developed

at trial.

Nethery's conclusion of bias

is premised on the judge's alleged friendship

with Officer McCarthy. The state habeas court

received conflicting affidavits from the trial

judge and Nancy Berry, Nethery's friend and

spiritual advisor, regarding the judge's

statements at the resentencing hearing. Berry

claimed to have heard the judge profess a

friendship with the victim; the judge denied

this and maintained that he was not personally

acquainted with the victim.

The record of the

resentencing hearing is silent with respect to

the judge's supposed reference to a friendship

with the victim, corroborating the judge's

version of events. The state habeas court found

as a matter of fact that the judge was not a

personal friend of the victim. Because it did

not follow on the heels of a full and fair

hearing, this finding is not entitled to the

statutory presumption of correctness.

Berry testified in the

evidentiary hearing conducted a quo, stating, as

she had in her affidavit, that she heard the

trial judge profess a friendship with the

decedent during the resentencing hearing. The

magistrate judge, citing her selective recall of

events, chose to discredit her testimony and

concluded that the "most petitioner has shown is

that the trial judge was offended and upset by

the brutal and senseless nature of petitioner's

crime." The magistrate judge found the record of

the hearing and the state trial judge's

affidavit more credible. Rule 52(a)'s command of

deference to findings of fact, particularly when,

as here, those findings are premised on

credibility assessments, compels our rejection

of this assignment of error.

II.

GRAND JURY COMPOSITION

It is well

established that the criminal defendant has no

constitutional right to a grand jury indictment

before trial in state criminal proceedings.

A deficient indictment will, however, provide a

basis for federal habeas relief if the defect is

so significant that the convicting court lacked

jurisdiction under state law.

Under Texas law, a grand jury

is composed of twelve grand jurors.

Once the grand jury is impaneled, nine grand

jurors constitute a quorum for doing business.

A review of pertinent statements in Texas

decisions, mostly in dicta and mostly from the

late 1800s and early part of this century,

suggests that a conviction after indictment by a

grand jury impaneled with more or less than 12

members is void.

Assuming, per arguendo, that

these cases reflect the current state of Texas

law, and that proof of the impanelment of less

than 12 grand jurors would constitute grounds

for reversal on collateral attack, Nethery has

failed to establish that controlling fact herein.

Nethery claims to have

learned from a fellow inmate, who was indicted

by the same grand jury, that the grand jury was

not lawfully formed. During the course of the

evidentiary hearing in this case, Nethery

introduced the transcript of a hearing in his

fellow inmate's case in which the foreman of the

grand jury noted in passing that only nine grand

jurors deliberated throughout the grand jury's

tour of duty.

The state objected to the

introduction of this transcript because the

issue in the previous case was whether the

indictment had been forged; thus, there never

had been an opportunity to develop fully the

testimony from the foreman with respect to the

number of grand jurors. The foreman did not

testify in the evidentiary hearing before the

magistrate judge.

Assuming, per arguendo, that

the foreman's testimony in an unrelated

proceeding was properly admitted under a hearsay

exception, and that this testimony can fairly be

read to establish the presence of only nine

grand jurors during deliberation of both cases,

the same result obtains. Texas law clearly

provides for indictment by a quorum of nine

grand jurors; the foreman's testimony, even if

accepted as reliable, would, in fairness,

establish only that this number was present when

the Nethery indictment was handed up.

Hugh Lucas, an Assistant

District Attorney, testified that he supervised

the operations of the grand jury on the day

Nethery was indicted, that twelve grand jurors

were impaneled, and that he personally witnessed

at least nine of them assemble to hear Nethery's

case. This testimony never has been contradicted

and is corroborated by court documents listing

the names of the 12 impaneled grand jurors. This

assignment of error is without merit.

III.

PROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT

Nethery

charges that certain statements made by the

prosecution during closing arguments improperly

pointed to his failure to testify. The Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals found the following

statement by Nethery's lawyer to have invited

reply:

The prosecutor, when they

were questioning you, told you it's not up to

the state to prove motive. That's right. Nothing

in the court's charge says they have to prove it.

But I'll say this: If you have lack of motive,

you're certainly entitled to consider that.

According to Brown, he'd finished. He was--both

of them [had] finished. Turning to go back to

their car. And you've got a man who knows that

he's facing two police officers with guns and

[he] gets out of the car and deliberately shoots

and kills a policeman. Where's the logic? What

reason is there?

In its closing the state

responded:

Motive? Mr. Goodwin wants a

motive. Mr. Goodwin wants a reason. You told us,

each and every one of you told us on voir dire

that we could not, in many cases, bring you a

motive or a reason and you agreed from that

witness stand that you would not force the State

to show you a motive. And I'm sure it was

explained to you that we can't show you a motive

or a reason because many times it is known only

to the defendant. It's in that head (pointing to

defendant). We can't cut that head open.

The trial court sustained a

defense objection to the statement and

instructed the jury to disregard it but refused

to declare a mistrial. The state argues that (1)

even if the statement could be interpreted as a

comment on Nethery's silence, it was invited;

(2) to the extent the reply exceeded the

invitation, if at all, the error was either

cured by the instruction; or (3) was harmless.

While we hesitate to endorse

the prosecution's remarks as an appropriate and

measured response to those of defense counsel,

we note that any unfair prejudice was, at most,

slight.

Defense counsel had opined

that the state's failure to prove a motive for

Nethery's conduct suggested a lack of criminal

responsibility. The state was entitled to make

an appropriate response. To the extent the

prosecution may have responded excessively, we

must view the error in light of the court's

curative instruction and consider whether the

residual impact had any "substantial and

injurious effect or influence in determining the

jury's verdict."

To say at this

point that the jury drew the adverse inference

Nethery feared would be speculative at best.

Nonetheless, even assuming the statement caused

each juror to consider Nethery's failure to take

the stand in his own defense and to draw an

adverse inference from it, we are not prepared

to say that this assumed error was harmful to

the extent required under the controlling

standard. Nor are we prepared to say that this

assumed error was not corrected by the court's

curative instruction.

Rather, we

hold that any error associated with the

prosecution's reply was cured at trial and, in

light of the overwhelming evidence of guilt, had

no substantial and injurious effect or influence

in the determination of Nethery's guilt or

proper sentence.

IV. JURY SELECTION

During the course of jury

selection the court excused for cause

prospective jurors William Keller and Debra

Pippi and declined defense invitations to excuse

several other venire members who indicated a

preference for imposing death as a penalty for

murder. Nethery complains of both decisions.

In Wainwright v. Witt

the Supreme Court approved the removal of a

prospective juror for cause where his views

would "prevent or substantially impair" the

performance of his duties in accordance with his

oath and the court's instructions. The Court

recognized that reliable assessment of the

juror's ability to set aside personal

convictions depends on the juror's demeanor and

credibility. A juror's bias need not be proven

with unmistakable clarity. Accordingly,

judgments made at trial about a juror's ability

to abide by the oath and the court's

instructions, notwithstanding moral convictions,

are accorded a presumption of correctness under

28 U.S.C. 2254(d).

Venire member Keller

repeatedly insisted that the death penalty was

per se inappropriate and pointedly answered that

he would vote "no" to the special issues

regardless of the instructions or the evidence,

in order to avoid its imposition. Only on cross-examination

did he testify that it was "possible" that he

could answer the special issues in the

affirmative.

On redirect by the state,

Keller reiterated that he would vote "no" to

prevent the imposition of the death penalty and

held to that position during the judge's final

examination. Venire member Pippi likewise

expressed her disapproval of the death penalty

and testified that she would find it difficult

to cast aside her convictions in favor of the

court's instructions. We conclude and hold that

the dismissal of Keller and Pippi did not

violate the standard announced in Witt.

Nethery

exercised peremptory challenges to remove the

venire members he identifies as having been

properly subject to strikes for cause. Even

counting the strikes he used on these jurors,

Nethery did not exhaust his peremptory

challenges.

He was not forced, therefore, to accept jurors

he found objectionable, and the court's refusal,

erroneous or otherwise, to strike for cause

those prospective jurors he removed with

peremptory challenges did not cause harm of

which Nethery may now complain.

V. MITIGATING EVIDENCE AND

SPECIAL ISSUES

In three distinct points of

error, Nethery asserts that the jury could not

give effect to mitigating evidence of his

intoxication in responding to the statutorily

mandated special issues. He first claims that

the special issues as they existed at the time

of his trial

did not allow the jury to consider evidence of

his intoxication or to incorporate their

response into the answers called for and, as a

result, the court's refusal to provide a

separate instruction resulted in a violation of

his eighth and fourteenth amendment rights.

He next claims that the

special issues failed to apprise the jury about

how it should consider evidence which was

probative of his future dangerousness and which

also mitigated his culpability. Lastly, he

argues that the special issues and instructions

allowed the jury to consider only evidence of

future dangerousness. We address these arguments

collectively.

In Penry v. Lynaugh,

the Supreme Court held that the Texas special

issues were inadequate to allow meaningful

consideration of the mitigating effect of

Penry's mental retardation. The Court based its

conclusion on the direct inverse relation

between the evidence's mitigating and

aggravating potential and the fact that the

special issues provided a means of expression

only to the aggravating character of this

evidence in relation to the second special issue--future

dangerousness. Thus, the jury's ability to

consider the mitigating effect in response to

one of the three questions was not present and

an additional instruction was necessary.

Nethery argues that the

mitigating effect of his intoxication likewise

had relevance beyond the scope of any question

asked in Texas' sentencing scheme and that the

absence of further instruction prevented the

jury from considering this evidence or from

expressing a favorable response. He also assails

the Texas scheme in its entirety because it

allegedly fails to provide the jury with

reasonable means of considering mitigating

evidence and directs attention unfairly towards

aggravating factors.

The Penry

court expressly declined a sweeping invalidation

of the Texas scheme; such would have required

announcing and applying a "new rule."

The Court thus did not invalidate the Texas

scheme in toto or mandate "special instructions

whenever [the accused] can offer mitigating

evidence that has some arguable relevance beyond

the special issues."

Rather, this

court has construed the holding in Penry to

require additional jury instructions only where

the "major mitigating thrust of the evidence is

beyond the scope of all the special issues."

We have held that the Texas special issues are

sufficiently broad in themselves to allow the

jury to give meaningful consideration to the

accused's voluntary intoxication.

Unlike the

permanent disability suffered by Penry,

Nethery's intoxication was a transitory

condition which could be given mitigating effect

in response to the first or second special

issues. Indeed, Nethery's trial counsel

recognized as much and so argued to the jury.

Nethery's arguments are either foreclosed by

controlling precedent or propose a new rule

which we may not apply on collateral review.

VI. FAILURE TO DEFINE

TERMS USED IN THE SPECIAL ISSUES

Nethery claims that the

meaning of the terms "deliberately," "probability,"

and "society" cannot be ascertained and thus

complains of their use in the special issues. We

have determined that these words have a common

meaning and adequately permit the jury to

effectuate its collective judgment.

Thus, consideration of this point is foreclosed.

VII. FAILURE TO INFORM THE

JURY OF THE EFFECT OF NOT ANSWERING THE SPECIAL

ISSUES

The jury was informed,

pursuant to Article 37.071 of the Texas Code of

Criminal Procedure, that it could return a

negative answer to any special issue if ten or

more of them so voted. An affirmative response

to any question required unanimity. The jury was

not told of the consequence of its failure to

muster fewer than ten "no" votes or 12 "yes"

votes. Nethery contends that the failure to so

advise the jury caused the jury's responses to

fall short of the heightened need for

reliability required of a verdict in a capital

case.

Nethery muses

that the jury's ignorance could lead to a

situation in which individual jurors felt

compelled to reach a consensus and, thus, one

lone juror, assuming that he would have to rally

another nine "no" votes, would vote "yes" even

though he felt the appropriate answer was "no."

This lone juror theory presumes that the juror

would disregard the court's instructions to

exercise independent judgment and vote according

to the evidence as presented and the law as

explained by the court.

Nethery

contends that the jury's ignorance about the

effect of its verdict could lead to a situation

in which jurors feel compelled to reach a

consensus because Texas juries are instructed,

pursuant to Article 37.071, that they "shall"

reach a verdict. We have previously held that

this type of claim--which is based on the

principle announced by the Court in Mills v.

Maryland--proposes

a new rule under Teague v. Lane.

Nethery's

conviction became final in 1986--two years

before Mills was decided. We thus do not reach

the merits of his claim. Granting relief on this

claim, in contravention of the ordinary

presumption that jurors follow the trial court's

instructions,

would require our fashioning a new rule of

criminal procedure.

This we decline to do.

The judgment of the district

court is AFFIRMED.

*****

KING, Circuit

Judge, dissenting:

I respectfully dissent from

the panel majority's affirmance of the district

court's denial of the writ of habeas corpus in

Nethery's case. My disagreement with the

majority is limited to its disposition of

Nethery's Eighth Amendment claim regarding his

mitigating evidence of voluntary intoxication at

the time of the crime.

I.

I initially note that I

believe that the Supreme Court's decision in

Graham v. Collins, --- U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct. 892,

122 L.Ed.2d 260 (1993), aff'g on other grounds,

950 F.2d 1009, 1027 (5th Cir.1992) (en banc),

would appear to require that the majority should,

as a threshold matter, address whether Nethery's

Penry claim

is barred under the nonretroactivity doctrine

first announced in Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288,

109 S.Ct. 1060, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989) (plurality

opinion). See Graham, --- U.S. at ----, 113 S.Ct.

at 897 ("Because this case is before us on

Graham's petition for a writ of federal habeas

corpus, 'we must determine, as a threshold

matter, whether granting [the habeas petitioner]

the relief he seeks would create a "new rule" '

of constitutional law.") (citation omitted).

The majority, however, cites

a prior panel decision of this circuit--that was

rendered after the Supreme Court's decision in

Graham--which reached the merits of a Penry

claim based on mitigating evidence of

intoxication without mentioning Teague. In

effect, that panel held that the Teague doctrine

does not bar the court from reaching the merits

in such a case. See James v. Collins, 987 F.2d

1116, 1121 (5th Cir.1993).

Although I believe that the panel decision in

James mistakenly ignored the Supreme Court's

decision in Graham regarding the effect of

Teague on Penry-type claims, I agree with the

majority that we appear to be bound by James.

See Burlington N.R. Co. v. Brotherhood of

Maintenance Way Employees, 961 F.2d 86, 89 (5th

Cir.1992) (prior panel decision binds subsequent

panel unless intervening en banc or Supreme

Court decision).

II.

Nevertheless,

even if this court were to apply Teague to

Nethery's case on a clean slate, I believe that

Nethery's Eighth Amendment rights were violated

under Supreme Court authority firmly in

existence well before his conviction became

final in 1986. See Nethery v. State, 692 S.W.2d

686 (Tex.Crim.App.1985), cert. denied,

474 U.S. 1110 , 106 S.Ct. 897, 88 L.Ed.2d

931 (1986). As I will explain below, I

believe cases such as Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 , 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d

929 (1976) (joint opinion of Stewart,

Powell & Stevens, JJ.), Lockett v. Ohio, 438

U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct. 2954, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978) (plurality),

and Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 102 S.Ct.

869, 71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982), dictate the result in

this case.

A. The instructions given

to Nethery's sentencing jury

In contending that his Eighth

Amendment rights were violated, Nethery argues

that the evidence of his intoxication at the

time of the crime could not be given adequate

mitigating effect under the three Texas "special

issues" submitted to his capital sentencing jury.

The majority holds that a jury could adequately

give mitigating effect to evidence of

intoxication if the jury was submitted these

three special issues. I do not quarrel with the

abstract holding that, in answering the "deliberateness"

query, a rational jury could adequately give

mitigating effect to evidence of intoxication at

the time of the crime.

My dissent is not based on

the operation of the statutory special issues in

isolation in Nethery's case; instead, it is

based on another instruction that the trial

court submitted along with the special issues

that, in effect, took all three of the special

issues out of operation with respect to

Nethery's mitigating evidence of intoxication.

Pursuant to a Texas statute

applicable to all criminal cases--capital and

non-capital--the trial judge instructed

Nethery's jury that:

Evidence of temporary

insanity caused by intoxication may be

introduced by the actor in mitigation of penalty

attached to the offense for which he is being

tried. "Intoxication" means disturbance of

mental and physical capacity resulting from the

introduction of any substance into the body.

Nethery v. State, 692 S.W.2d

686, 711 (Tex.Crim.App.1985) (quoting from

Nethery's jury instruction) (emphasis added).

A reasonable

juror

could read that instruction as providing that

Nethery's evidence of intoxication could not be

considered at all--including under the special

issues--unless Nethery was so intoxicated that

he was rendered temporarily insane. Indeed, this

is precisely how the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals interprets § 8.04. See Tucker v. State,

771 S.W.2d 523, 534 (Tex.Crim.App.1988) ("[T]he

[§ 8.04] instruction required the jury to find

that [the defendant's] intoxication at the time

of the killings rendered her temporarily insane

before they could consider her drug use in

mitigation of punishment. The charge on its face

instructed the jury to consider the mitigating

evidence only in this light, thereby implying

that it may not be considered for any other

purpose.") (emphasis added); see also Volanty v.

Lynaugh, 874 F.2d 243, 244 (5th Cir.1989). Of

course, while intoxication that is so severe

that it rises to the level of temporary insanity

is quintessential mitigating evidence, so is

intoxication that is not so severe as to be

tantamount to a state of insanity.

See Bell v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 637, 640, 98 S.Ct.

2977, 2979, 57 L.Ed.2d 1010 (1978) (companion

case to Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586, 98 S.Ct.

2954, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978)); see also Elliott

v. State, 1993 WL 109394 (Tex.Crim.App., 1993)

(Clinton, J., dissenting); Ex Parte Rogers, 819

S.W.2d 533, 537 (Tex.Crim.App.1991) (Clinton,

J., dissenting, joined by Baird & Maloney, JJ.).

Even as early as Jurek, in

1976, total preclusion of a capital sentencing

jury's ability to consider any species of

constitutionally relevant mitigating evidence

was held to be an Eighth Amendment violation.

See Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. at 272, 96 S.Ct. at

2956 ("[T]he constitutionality of the Texas

procedures turns on whether the [special issues]

allow consideration of particularized mitigating

factors."); see also Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S.

at 604, 98 S.Ct. at 2964; Eddings v. Oklahoma,

455 U.S. at 110, 102 S.Ct. at 874. Because

Nethery's jury was entirely precluded from

considering the evidence of his non-insane state

of intoxication, I believe that the § 8.04

instruction given by the trial judge in

Nethery's case was a straight-forward violation

of this well-established Eighth Amendment

principle.

B.

Is this claim properly before this court?

Nethery has

not specifically argued that the § 8.04

instruction was the source of the Eighth

Amendment violation that he claims occurred at

his trial. Rather, he has simply argued that

mitigating evidence of his intoxication at the

time of the crime could not be given proper

mitigating effect under the statutory special

issues submitted to his jury. The majority

believes that the issue of the constitutionality

of the operation of § 8.04 in Nethery's case is

not properly before this court. I respectfully

disagree.

I believe that we must

necessarily address this specific question as a

collateral issue to the larger Eighth Amendment

claim raised. See Ex parte Rogers, 819 S.W.2d at

537 (Clinton, J., dissenting, joined by Baird &

Maloney, JJ.). As the Supreme Court held in

Graham, cases such as Lockett and Eddings

require that a capital defendant's sentence be

upheld so long as all relevant mitigating

evidence was placed within "the effective reach

of the sentencer." Graham, --- U.S. at ----, 113

S.Ct. at 902. In order for the majority to hold

that Nethery's evidence of intoxication was

properly considered as mitigating evidence under

the instructions given to his capital sentencing

jury, it thus must agree that Nethery's evidence

of intoxication was not beyond the effective

reach of his jury under the special issues. In

view of the § 8.04 instruction given by

Nethery's trial judge in addition to the

statutory special issues, I cannot agree with

that conclusion.

Furthermore, I believe that

we may not avoid addressing the effect of the §

8.04 instruction because, in considering a

challenge to jury instructions, a court must

review the entire charge in order to determine

the effect of the alleged defect. See California

v. Brown, 479 U.S. at 543, 107 S.Ct. at 840 (in

a capital case, the Court stated that "reading

the charge as a whole, as we must ..."); see

also United States v. Shaw, 894 F.2d 689, 693

(5th Cir.1990); United States v. Washington, 819

F.2d 221, 226 (9th Cir.1987) (asking "whether as

a whole [the jury instructions] were misleading

or inadequate"). Reviewing the entire sentencing

charge in Nethery's case in order to determine

whether Nethery's evidence of intoxication was

in "the effective reach" of his jury, Graham,

--- U.S. at ----, 113 S.Ct. at 902, I do not

believe that we simply may ignore the § 8.04

component of the capital sentencing charge,

notwithstanding Nethery's failure precisely to

raise that particular issue. For these reasons,

I respectfully dissent.

*****

It became apparent during

arguments in the course of the hearing below

that Nethery sought to argue that Texas law not

only requires the impaneling of twelve grand

jurors but that twelve grand jurors must be

present to deliberate in every case. The state

court did not address this contention.

The district court, citing

Drake v. State, 25 Tex.App. 293, 7 S.W. 868

(1888) and noting the state's waiver of the

exhaustion requirement, determined that Texas

law imposed no such requirement. Based on our

review of the plain language of the Texas

Constitution and its Code of Criminal Procedure,

as well as Texas case law, we agree. Hodges v.

State, 604 S.W.2d 152 (Tex.Crim.App.1980)

(holding nine grand jurors constitute a quorum

for returning indictments); see also In re

Wilson, 140 U.S. 575, 11 S.Ct. 870, 35 L.Ed. 513

(1891) (no jurisdictional defect where

sufficient number of grand jurors voted to

indict notwithstanding fact that an insufficient

number were impaneled); 38 AM.JUR.2D Grand Jury

§ 16 (1968) ("Unless the statute is mandatory as

to the number of grand jurors acting, the

excusing or absence of some of the panel will

not affect an indictment if enough remain to

constitute the number necessary to concur.").

Since Chapman, the Court has

drawn a distinction between constitutional

violations "of the trial type" and "structural

defects in the constitution of the trial

mechanism, which defy analysis by harmless error

standards." Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S.

----, 111 S.Ct. 1246, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991).

The Court recently has held that "trial type

error" will serve as a basis for habeas relief

only if it "had substantial and injurious effect

or influence in determining the jury's verdict."

Brecht v. Abrahamson, --- U.S. ----, 113 S.Ct.

1710, 123 L.Ed.2d 353 (1993). Chapman error, as

alleged here, is trial error.

When the trial court errs in

overruling a challenge for cause against a

venireman, the defendant is harmed only if he

uses a peremptory strike to remove the venireman

and therefore suffers a detriment from the loss

of a strike. Error is preserved only if the

defendant exhausts his peremptory challenges, is

denied a request for an additional peremptory

challenge, identifies a member of the jury as

objectionable and claims that he would have

struck the juror with a peremptory challenge.

At the time of trial the

issues were:

(1) whether the conduct of

the defendant that caused the death of the

deceased was committed deliberately and with the

reasonable expectation that the death of the

deceased or another would occur;

(2) whether there is a

probability that the defendant would commit

criminal acts of violence that would constitute

a continuing threat to society; and

(3) if raised by the

evidence, whether the conduct of the defendant

in killing the deceased was unreasonable in

response to the provocation, if any, by the

deceased.

Unlike the dissent, we do not

believe we have before us the question whether

the jury instruction as given, pursuant to

section 8.04 of the Texas Penal Code,

affirmatively precluded the jury's consideration

of Nethery's purported intoxication. There was

no prior submission to that effect in either the

state or federal courts. In fact, as the dissent

notes, the Texas courts found the objection

Nethery actually presented to be procedurally

barred and also found that he was not so

intoxicated at the time of the offense as to

warrant submission of the temporary insanity

instruction. Further, not only did Nethery fail

to preserve this point, he actually requested a

definition of insanity--basing his later

challenges on the denial thereof--which would

have created the precise prejudice the dissent

fears.

The dissent argues that the

Texas courts have twice excused procedural

defaults where the defendant sought to argue a

Penry claim because "Penry 'constituted a

substantial change in the law....' " Selvage v.

Collins, 816 S.W.2d 390, 392 (Tex.Crim.App.1991)

(citing Black v. State, 816 S.W.2d 350, 374 (Tex.Crim.App.1991)).

It is unclear how this reading will be affected

by the Supreme Court's subsequent and more

restrictive reading of Penry in Graham. More

importantly, as the dissent points out, the

defaulted claim would be the total preclusion of

a jury's ability to consider mitigating evidence.

That objection was recognized, again, as the

dissent points out, as early as 1976. See Jurek

v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 , 96 S.Ct. 2950, 49 L.Ed.2d

929 (1976). We conclude that the claim

has not been presented to us at all and, in any

event, that Texas courts would find it to be

barred. Accordingly, we do not address its

merits.

(1) Whether the conduct of

the defendant that caused the death of the

deceased was committed deliberately and with the

reasonable expectation that the death of the

deceased or another would result;

(2) Whether there is a

reasonable probability that the defendant would

commit criminal acts of violence that would

constitute a continuing threat to society;

(3) If raised by the

evidence, whether the conduct of the defendant

in killing was unreasonable in response to the

provocation, if any, by the deceased.

TEX.CODE CRIM.PRO. Art.

37.071(b) (Vernon's 1981). Nethery's jury was

given three special issues based in substance on

these three statutory special issues.

§ 8.04. Intoxication.

(a) Voluntary intoxication

does not constitute a defense to the commission

of a crime.

(b) Evidence of temporary

insanity caused by intoxication may be

introduced by the actor in mitigation of the

penalty attached to the offense for which he is

being tried....

Because of § 8.04, Texas

criminal juries may not consider evidence of a

defendant's voluntary intoxication for any

reason during the guilt/innocence phase; a jury

may only consider such evidence during the

sentencing phase, and then only if the

defendant's intoxication rose to the level of

temporary insanity. See Tucker v. State, 771 S.W.2d

523, 534 (Tex.Crim.App.1988).