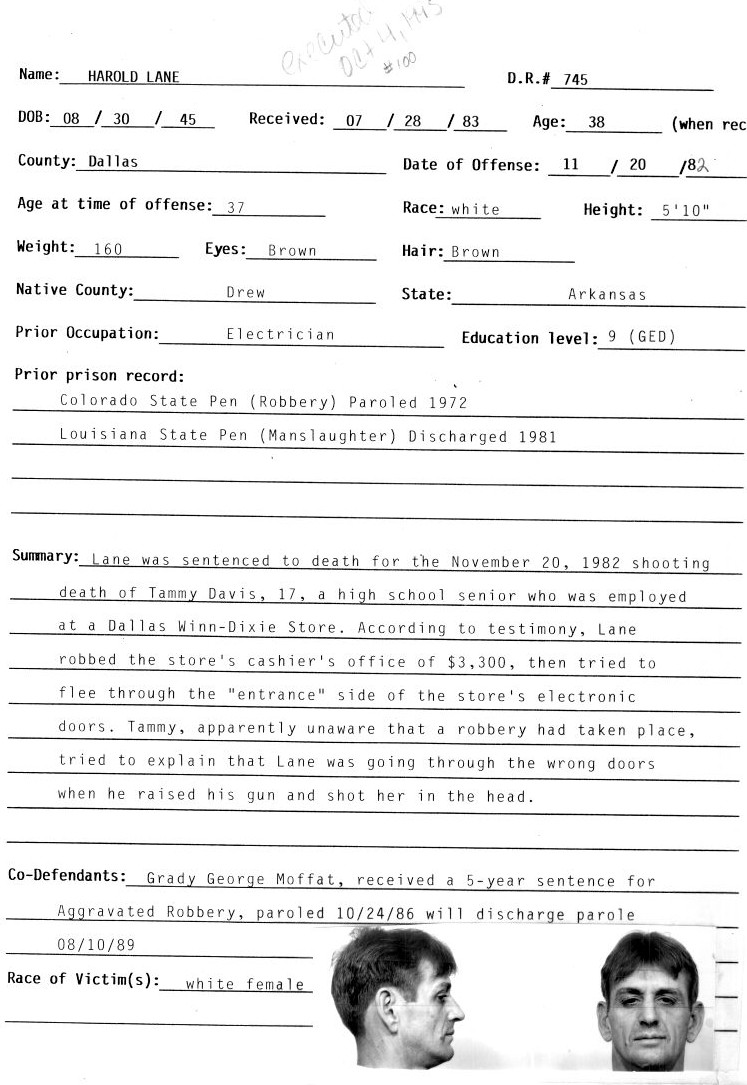

Texas today put to death a man who killed a 17-year-old girl in the robbery of a Dallas supermarket in 1982.

Earlier in the day, the United States Supreme Court refused to block the execution of the inmate, Harold Joe Lane, by injection.

Mr. Lane, 50, was pronounced dead at 6:28 P.M., nine minutes after the lethal drugs began flowing into his arm.

He was the first Texas convict put to death under new execution procedures. Previously, the punishment was carried out after midnight.

Lawmakers made the change after agreeing that lawyers and judges are more accessible during the day.

Mr. Lane's lawyer, Michael Schulman, argued in a last-minute appeal that the jurors in his client's trial should have been told that an accomplice had received only a five-year prison term.

The appeal was rejected on Tuesday by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, and early today by the Supreme Court on a 7-to-2 vote.

Mr. Lane had said he was high on drugs and alcohol when he robbed the Winn-Dixie store. He shot the girl, Tammy Davis, a cashier, when he became frustrated by an automatic door that would not open as he tried to flee.

Miss Davis, apparently unaware that a robbery was taking place, told Mr. Lane he was trying to go out the "in" door and pointed out the button that would let him out. He raised his .357 magnum and shot her in the head, the authorities said. He was captured after firing at police during a chase.

Miss Davis's mother, Brenda Ruiz, said the execution "finally closes the book on the trauma that has taken place."

"I have come here to see justice finally is served in this case," she said. The new law would have allowed her to view the execution, but the renovations to make room in the death chamber had not been completed.

Mr. Lane had a long criminal history, including imprisonment in Colorado for robbery and assault and in Louisiana for manslaughter. In a recent interview, he was sarcastic about the milestone that would be set by his execution, his becoming the 100th inmate to be executed in Texas since the state resumed executions in 1982.

"Great honor, huh?" he said. "It's something to tell my kids. Something for them to look back on. My dad is 100."

IN THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF

APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH

CIRCUIT

No. 94-11080

HAROLD JOE LANE,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

WAYNE SCOTT,

Director, Texas

Department of

Criminal Justice,

Institutional

Division, Respondent-Appellee.

Appeal from the

United States

District Court for

the Northern

District of Texas

(3:92 CV 1500 R)

June 16, 1995

Before KING, DAVIS and WIENER, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

* Harold Joe Lane petitions this court for a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254 claiming that his Texas state court conviction for capital murder is constitutionally infirm. Specifically, Lane contends that certain mitigating evidence-- namely, his co-defendant's lesser sentence and certain facts surrounding his prior conviction for manslaughter-- was improperly excluded at the sentencing phase of his trial, in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. We affirm.

I. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

Because the issues in this case are purely legal, a detailed exposition of the facts giving rise to Lane's conviction for capital murder is not necessary. Suffice it to say that, while robbing a grocery store in Dallas, Texas, Lane shot and killed a seventeen year-old female cashier with a .357 Magnum.1 A state jury convicted Lane of capital murder and sentenced him to death.

On direct appeal, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed and remanded for a new trial due to an error in the jury selection process. Lane v. State, 743 S.W.2d 617 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1987). Upon retrial, a jury again found Lane guilty of capital murder. The jury answered two special statutory issues in the affirmative and, in accordance with Texas law, the state trial judge sentenced Lane to death. See TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. ANN. arts. 37.071(b) & (e) (West 1981).2 On December 4, 1991, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Lane's conviction. Lane v. State, 822 S.W.2d 35 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1991) (en banc). On May 18, 1992, the United States Supreme Court denied Lane's petition for a writ of certiorari. Lane v. Texas, 112 S. Ct. 1968 (1992).

Following the exhaustion of Lane's direct appeals, the state trial court set an execution date of July 23, 1992. On July 20, 1992, Lane filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus and a motion for a stay of execution, both of which were denied by the state trial court and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in unpublished decisions. See Ex Parte Lane, No. 23,826-01 (Tex.

Ct. Crim. App. July 22, 1992), cert. denied, 113 S. Ct. 2 (1992). deliberately and with the reasonable expectation that the death of the deceased or another would result; (2) whether there is a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society; and (3) if raised by the evidence, whether the conduct of the defendant in killing the deceased was unreasonable in response to the provocation, if any, by the deceased.

. . . .

(e) If the jury returns an affirmative finding on each issue submitted under this article, the court shall sentence the defendant to death. If the jury returns a negative finding on any issue submitted under this article, the court shall sentence the defendant to confinement in the Texas Department of Corrections for life. . . .

TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. ANN. art. 37.071 (West 1981). It should be noted that article 37.071 has since been amended. See TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. ANN. art. 37.071 (West 1995).

Upon denial of his petition by the state courts, on July 22, 1992-- just one day prior to his scheduled execution-- Lane filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus with the federal district court in the Northern District of Texas. Because there was not sufficient time to review the merits of Lane's petition prior to his scheduled execution, the district court granted Lane's request for a stay of execution pending disposition of his petition on the merits. The district court then referred Lane's petition to a Magistrate Judge.

On September 6, 1994, the Magistrate Judge recommended that Lane's petition be denied on the merits. On October 24, 1994, the district court adopted the Magistrate Judge's findings, denied Lane's petition on the merits, and vacated its earlier stay of execution. On November 22, 1994, the district court issued a certificate of probable cause. On November 23, 1994, Lane filed a timely notice of appeal to this court.

II. ANALYSIS

In his petition to this court, Lane raises essentially two points of error: (1) the state trial court erred in excluding evidence of his co-defendant's lesser sentence; and (2) the state trial court erred in excluding evidence relating to the inebriation of the victim of Lane's prior conviction for manslaughter.3 Lane contends that both of these evidentiary exclusions violated his right to have the jury give full consideration to mitigating circumstances of his crime and an individualized sentencing as required by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

A. Co-Defendant's Sentence.

Lane contends that the state trial court erred in excluding evidence regarding the sentence received by his co-defendant, Grady Moffett. Specifically, Lane sought to introduce evidence that Moffett, who played an active role as an armed lookout in the robbery, successfully plea bargained for a five year sentence. Lane argues that the jury should have been informed of Moffett's lesser sentence because it was relevant to statutory special issue number two, which asks the jury to determine "whether there is a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society." See TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. ANN. art.

37.071(b)(2) (West 1981). If the jury had known that the district attorney was willing to accept a plea bargain of only five years for Moffett, Lane argues, it indicates that the district attorney did not believe that Moffett posed a continuing threat to society. If Moffett-- an armed accomplice of Lane's-did not pose a continuing threat to society, then the jury could infer that neither did Lane, and it would have answered special issue number two "no," resulting in the imposition of a life sentence rather than the death penalty. See TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC.

ANN. art. 37.071(e) (West 1981).

In Lockett v. Ohio,438 U.S. 586 (1978), a plurality of the Supreme Court held that the Constitution requires that the sentencer in a capital case be permitted to consider "any aspect of a defendant's character or record and any of the circumstances of the offense that the defendant proffers as a basis for a sentence of death." Id. at 606. While the range of relevant mitigating evidence is broad, see McKoy v. North Carolina,494 U.S. 433, 441 (1990), the Supreme Court has never spoken as to whether a co-defendant's sentence is properly within the ambit of mitigating evidence.

Lane relies primarily upon Parker v. Dugger,498 U.S. 308 (1991), which he contends "stands for the proposition that, the prosecution's disparate treatment of co-defendants who share equal or similar degrees of culpability for a capital murder is constitutionally relevant mitigating evidence and must be admitted into evidence during the capital sentencing phase."

In Parker, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the Florida courts for reconsideration of the appropriateness of the death penalty because the Florida Supreme Court had misread the trial court's factual findings and mistakenly concluded that "[t]he trial court found no mitigating circumstances to balance against the aggravating factors . . . ." Id. at 311 (emphasis added). The Supreme Court noted that the defendant had indeed introduced evidence of certain nonstatutory mitigating factors, including inter alia, evidence that none of his co-defendants had received the death penalty for their role in the murder. Id. at 314.

In particular, the Court noted that one of Parker's co-defendants, Billy Long, had admitted to being the triggerman in the murder for which Parker had received the death penalty, yet he had been allowed to plead guilty to second-degree murder. Id. Because the state supreme court in Parker mistakenly characterized the record as completely devoid of evidence of mitigating circumstances, the Supreme Court had no confidence in the state supreme court's affirmance of the death sentence and remanded the case for explicit consideration of the mitigating circumstances proffered by Parker at trial. Id. at 318-20, 322-23.

While Lane contends

that Parker suggests

that evidence of an

equally or more

culpable co-defendant's

sentence is

constitutionally

relevant mitigating

evidence, the Parker

Court was not asked

to address this

issue directly and

we decline the

invitation to

interpret Parker's

dicta so broadly.

Accord Frey v.

Fulcomer, 974 F.2d

348, 366 n.22 (3d

Cir. 1992), cert.

denied, 113 S. Ct.

1368 (1993). Indeed,

in Brogdon v.

Blackburn, 790 F.2d

1164 (5th Cir.

1986), cert. denied,

B. Prior Offense.

Lane next argues that the state trial court erred in excluding Defendant's Exhibit 15, which was a certified copy of the Louisiana Supreme Court opinion in Lane v. Louisiana, 292 So.

2d 711 (La. 1974), the opinion rendered with regard to Lane's 1973 conviction for manslaughter in Louisiana. In his brief, Lane argues that [o]f all of [Lane's] collateral offense[s], the only one resulting in loss of life was his 1973 Manslaughter Conviction in Louisiana. What the excluded exhibit would have shown in the context of the jury's evaluation of the issue of future dangerousness, is that the coroner found that the victim had a blood alcohol content of .258 percent. . . . Furthermore, Mr. Lane asserted that his action[s] were taken in self defense, because prior to the shooting the decedent came at him in a threatening manner with a pool stick or cue or both.

In short, Lane contends that if the jury had known that his manslaughter victim was drunk, it would have been more inclined to answer special issue number two "no," and conclude that Lane did not pose a continuing threat to society. See TEX. CODE CRIM.

PROC. ANN. art. 37.071(b)(2) (West 1981). Aside from the fact that it is difficult to find a rational link between the drunkenness of a victim and the perpetrator's future dangerousness, we find this argument to lack merit for the simple reason that the information Lane argues should have been placed before the jury-- the victim's drunkenness-- was actually placed before the jury during closing argument. Lane's counsel stated to the jury prior to sentencing: When you go back there you're going to find out something and it will also tie up that evidence we brought up at the first phrase [sic] of the trial about alcohol intoxication. It will tell you a couple of things. First of all, the man that was killed was a point .258. Translation-- he was dead drunk. This is an important part of that [manslaughter] conviction.

. . .

In addition, the record indicates that Defendant's Exhibit 15 was ultimately admitted in a revised form which deleted portions of the Louisiana Supreme Court opinion which dealt with Louisiana law. The portion relating to the victim's drunkenness was, however, permitted to remain, and the redacted version of Defendant's Exhibit 15 was admitted before the jury with the agreement of both parties. The redacted version states that "[t]here is no expert testimony as to how much the group had been drinking, except the coroner's finding that the victim had a blood alcohol content of .258 percent." Accordingly, the evidence that Lane argues is mitigating was placed before the jury and his argument that it was error to exclude the original version of Defendant's Exhibit 15 is without merit.

III. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the district court denying Lane's petition for a writ of habeas corpus is in all respects AFFIRMED.

*****

*Local Rule 47.5 provides: "The publication of opinions that have no precedential value and merely decide particular cases on the basis of well-settled principles of law imposes needless expense on the public and burdens on the legal profession." Pursuant to that Rule, the court has determined that this opinion should not be published.

1 A detailed account of the facts surrounding the murder can be found in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals' published opinion. See Lane v. State, 822 S.W.2d 35, 37-38 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App. 1991).

2 The relevant portion of article 37.071 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure in effect at the time of Lane's trial provided: (b) On conclusion of the presentation of the evidence, the court shall submit the following issues to the jury: (1) whether the conduct of the defendant that caused the death of the deceased was committed

3 Lane did not present either of these claims to the district court below nor to the state courts as required by 28 U.S.C. § 2254(b) and (c). As a general rule, the failure to present issues to the district court results in a waiver of those issues on appeal. The state's brief addresses both claims, noting that "[r]ather than address whether it would constitute a `manifest injustice' for the Court to refuse to consider the claims, the Director has chosen to address the merits of the claim instead." Moreover, despite Lane's failure to exhaust these claims in state court, the state has expressly waived the exhaustion requirement in this case.

4 Even if we were to accept Lane's contention that Parker indicates that the Supreme Court considers an equally or more culpable co-defendant's sentence to be constitutionally required mitigating evidence (which we explicitly do not accept), this interpretation of Parker's dicta would be unavailing to Lane. In Parker, the evidence indicated that Parker's co-defendant, Billy Long, was the actual triggerman in the murder of the victim, making Long equally or more culpable than Parker. By contrast, Lane's co-defendant, Grady Moffett, was not equally or more culpable than Lane because although he served as an armed lookout during the robbery, there is no evidence that he took an active part in the murder of Tammy Davis. In any event, the rule of law argued for by Lane would be a "new rule" of constitutional law which could not be retroactively applied to Lane under the edict of Teague v. Lane,489 U.S. 288 (1989).