Background: Petitioner, convicted in state court

of murder and sentenced to death, 259 Ga. 770, 386 S.E.2d 509,

sought federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for

the Middle District of Georgia, No. 96-00097-3:CV-DF, Duross

Fitzpatrick, J., denied petition. Petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Tjoflat, Circuit

Judge, held that:

(1) petitioner had no due process right to psychiatric assistance;

(2) even if petitioner had right to psychiatric assistance, trial

court met its obligations under due process clause;

(3) state court's determination that claim that prosecutor's

participation in hearings on petitioner's requests for funds to

retain psychiatric expert violated due process was subject to

harmless error analysis was not contrary to, or unreasonable

application of, federal law;

(4) any error in not providing ex parte hearings on requests for

funds was harmless;

(5) petitioner failed to provide evidence discrediting prosecutor's

specific, nonracial reasons for using peremptory strikes against

African-Americans;

(6) claim that trial court seated two jurors who were impermissibly

predisposed toward death sentence was procedurally defaulted; and

(7) counsel did not render ineffective assistance. Affirmed.

TJOFLAT, Circuit Judge:

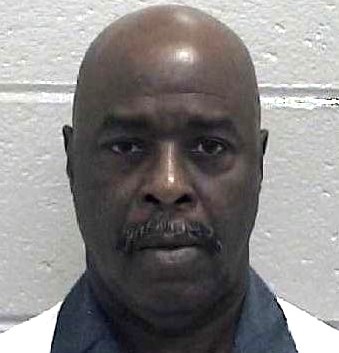

Petitioner John Washington Hightower, a Georgia prisoner, seeks a

writ of habeas corpus setting aside his 1988 convictions and

sentences for capital murder. The district court denied his petition.

We affirm.

The Supreme Court of Georgia summarized the facts

of this case as follows:

The defendant was married to Dorothy Hightower.

Her brother stopped by their home early in the morning of July 12,

1987, to pick up his daughter. Dorothy Hightower's car was gone. The

brother entered the home and found that Dorothy Hightower and her

two daughters, Evelyn and Sandra Reaves, had been shot. Evelyn

Reaves was still alive, but died two days later. Sandra Reaves and

Dorothy Hightower were dead. The brother's daughter was unharmed.

Two and one-half hours later, the defendant was

arrested driving his wife's car. Inside the car was a bloody

handgun. He confessed later that morning. He told police that he and

his wife had been having marital problems, and he had purchased the

murder weapon the day before. He hid it under his pillow until 3:00

a.m., when he shot his wife.

He then went to the bedroom occupied by

his stepdaughter Sandra Reaves. She got out of bed, but then lay

back down. He shot her in the head. Evelyn Reaves tried to leave the

house, but the defendant caught her and shot her three times.

Hightower v. State, 259 Ga. 770, 386 S.E.2d 509, 510 (1989).

After a trial held from April 28, 1988, to May 4,

1988, a jury in Morgan County, Georgia,FN1 convicted Hightower of

three counts of murder. In the penalty phase, the jury found an

aggravating circumstance as to each murder, namely, that Hightower

had committed each murder in the course of the commission of another

murder.FN2 The jury recommended death sentences on each of the three

counts of murder. The trial court entered these sentences as

required by Georgia law.FN3

FN1. Hightower was indicted in Baldwin County on

July 14, 1987. At a hearing on January 15, 1988, the superior court

granted Hightower's motion for a change of venue, and ordered that

venue be changed to Morgan County for trial. On February 25, 1988,

the court quashed the indictment on the ground that African-Americans

were underrepresented on the venire from which the grand jury had

been drawn.

A new indictment was returned on March 18, 1988,

and Hightower was arraigned on April 15, 1988. On April 20, 1988,

the superior court issued an order nunc pro tunc January 15, 1988,

incorporating into the record of the new case all motions, orders,

and rulings from the earlier case.

FN2. O.C.G.A. § 17-10-31 requires that a death

sentence be supported by “a finding of at least one statutory

aggravating circumstance.” One sufficient aggravating circumstance

for murder is that it “was committed while the offender was engaged

in the commission of another capital felony or aggravated battery.”

O.C.G.A. § 17-10-30. Hightower's jury found that (1) the murder of

Dorothy Hightower was committed while Hightower was engaged the

commission of the murder of Evelyn Reaves, (2) the murder of Sandra

Reaves was committed while Hightower was engaged in the commission

of the murder of Dorothy Hightower, and (3) the murder of Evelyn

Reaves was committed while Hightower was engaged in the commission

of the murder of Sandra Reaves.

FN3. O.C.G.A. § 17-10-31 provides that “[w]here a

statutory aggravating circumstance is found and a recommendation of

death is made, the court shall sentence the defendant to death.”

Hightower sought, but was denied, a new trial.

The Georgia Supreme Court affirmed Hightower's convictions on direct

appeal, Hightower v. State, 259 Ga. 770, 386 S.E.2d 509 (1989), and

denied his motion for reconsideration. The Supreme Court of the

United States denied Hightower's petition for a writ of certiorari,

Hightower v. Georgia, 498 U.S. 882, 111 S.Ct. 230, 112 L.Ed.2d 184

(1990), and his petition for rehearing, Hightower v. Georgia, 498

U.S. 995, 111 S.Ct. 549, 112 L.Ed.2d 557 (1990).

Hightower then petitioned the Superior Court of

Butts County, Georgia, for a writ of habeas corpus.FN4 After an

evidentiary hearing, the court denied his petition. The Georgia

Supreme Court denied Hightower's application for probable cause to

appeal and his subsequent motion for reconsideration. The Supreme

Court of the United States denied Hightower's petition for a writ of

certiorari, Hightower v. Thomas, 515 U.S. 1162, 115 S.Ct. 2618, 132

L.Ed.2d 860 (1995), and his petition for rehearing, Hightower v.

Thomas, 515 U.S. 1183, 116 S.Ct. 30, 132 L.Ed.2d 912 (1995).

FN4. Hightower petitioned that court because he

was incarcerated in Butts County.

Having pursued all state court avenues of relief,

Hightower sought habeas corpus relief in the United States District

Court for the Middle District of Georgia. The district court denied

his petition, concluding on the basis of the records of the state

court proceedings that none of his claims had merit. FN5 The

district court thereafter granted Hightower's application for a

certificate of appealability pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c),

concluding that he had made a “substantial showing of the denial of

a constitutional right” with respect to each of his claims.

In this appeal, however, Hightower challenges the

district court's disposition only of a portion of his claims. FN6 He

contends that the state trial court committed constitutional error

by (1) failing to provide him with the assistance of a qualified

psychiatrist as required by Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct.

1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985), and by neglecting to conduct hearings on

his Ake requests ex parte; (2) allowing the prosecutor peremptorily

to strike African-Americans from the jury, in contravention of

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69

(1986); and (3) permitting jurors unconstitutionally biased in favor

of the death penalty to serve on his jury. He also claims that his

two court-appointed lawyers provided constitutionally ineffective

assistance under Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct.

2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984).

FN5. The court also denied Hightower's Federal

Rule of Civil Procedure 59(e) motion to alter and amend the judgment.

FN6. Hightower has abandoned the following claims

by not including them in his brief: (1) the prosecutor engaged in

various forms of misconduct before and during the trial, depriving

him of his rights under the Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Fourteenth

Amendments to a fair trial and a reliable sentencing proceeding; (2)

the trial court violated his rights under the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments by failing to have all proceedings against him

transcribed and made part of the record; (3) the State obtained his

confession and used it against him at trial in contravention of the

Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments; (4) the trial court

violated his rights under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments by

providing misleading and incomplete instructions to the jury during

the penalty phase of his trial; (5) the trial court violated his

Fourteenth Amendment due process rights by allowing the prosecutor

to introduce allegedly inflammatory victim impact evidence; and (6)

his attorneys were constitutionally ineffective in numerous ways

beyond those cited in his brief to us.

* * *

Hightower raises two separate claims under Ake v.

Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985). We

address these in turn.

Hightower first claims that he was denied his

rights under Ake to the assistance of a competent psychiatrist.

Hightower unsuccessfully raised this claim on direct appeal to the

Georgia Supreme Court.FN7 Hightower v. State, 259 Ga. 770, 386 S.E.2d

509, 511 (1989). Thus, under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d), for Hightower to

prevail on this claim, the decision of the Georgia Supreme Court

must have been “contrary to, or ... an unreasonable application of,

clearly established” United States Supreme Court precedent, or

“based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the

evidence.” We hold that it was not. Because Hightower failed to make

the threshold showing required to trigger his rights under Ake, and

received defense funds that he could have used for a psychiatric

expert, his claim fails.

FN7. Hightower later brought this claim before

the Superior Court of Butts County. That court refused to review the

claim, citing Gunter v. Hickman, 256 Ga. 315, 348 S.E.2d 644 (1986).

Gunter held that an “issue ... actually litigated, i.e., raised and

decided [on] direct appeal ... cannot be reasserted in habeas corpus

proceedings” in Georgia state courts. Id. at 644-45 (citations

omitted).

The Supreme Court in Ake considered the

constitutional right of indigent criminal defendants to psychiatric

assistance. In that case, Ake, the defendant, notified the trial

court during a pretrial conference of his intention to raise an

insanity defense, and requested the appointment of, or funds to hire,

a psychiatrist. Ake, 470 U.S. at 72, 105 S.Ct. at 1090. The court

denied the request. Id. at 72, 105 S.Ct. at 1090-91. At the guilt

phase of Ake's trial, “there was no expert testimony for either side

on Ake's sanity at the time of the offense,” even though “his sole

defense was insanity.” Id. at 72, 105 S.Ct. at 1091 (emphasis

omitted). The jury found him guilty. Id. at 73, 105 S.Ct. at 1091.

At the sentencing phase, Ake, without a psychiatric expert, could

not rebut the testimony of state psychiatrists who claimed he was

“dangerous to society,” and could not “introduce on his behalf [psychiatric]

evidence in mitigation of his punishment.” Id. at 72, 105 S.Ct. at

1091. The jury returned a death sentence. Id.

The Supreme Court ruled in Ake's favor, holding

under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment that when a

defendant demonstrates to the trial judge that his sanity at the

time of the offense is to be a significant factor at trial, the

State must, at a minimum, assure the defendant access to a competent

psychiatrist who will conduct an appropriate examination and assist

in evaluation, preparation, and presentation of the defense. 470 U.S.

at 83, 105 S.Ct. at 1096.

The Court found that the trial court was

adequately “on notice” that “Ake's mental state at the time of the

offense was a substantial factor in his defense,” id. at 86, 105

S.Ct. at 1097, due in large part to the following facts: (1) Ake's

sole defense was insanity; (2) the trial court, sua sponte, had

ordered that Ake be examined by a psychiatrist to determine the

cause of his “bizarre” behavior at arraignment; (3) a state

psychiatrist later found Ake incompetent to stand trial; (4) Ake was

deemed competent “only on the condition that he be sedated” with

medication during the trial; and (5) psychiatrists who examined Ake

for competency did so within six months of the offense, and opined

that his “mental illness might have begun many years earlier.” Id.

at 86, 105 S.Ct. at 1098.

Because “[a] defendant's mental condition is not

necessarily at issue in every criminal proceeding,” id. at 82, 105

S.Ct. at 1096, the right to psychiatric assistance is not automatic.

Rather, this right hinges upon the sufficiency of the defendant's

preliminary showing to the trial court that there is a “substantial

basis for the defense” that the expert will assist in presenting.

Moore v. Kemp, 809 F.2d 702, 712 (11th Cir.1987) (en banc).

While defense counsel “cannot be expected to

provide the court with a detailed analysis of the assistance an

appointed expert might provide,” he is nonetheless “obligated to

inform himself about the specific scientific area in question and to

provide the court with as much information as possible concerning

the usefulness of the requested expert” to the defense. Id. The

trial court must then examine the evidence before it, make all

necessary inferences, and determine whether the provision of

psychiatric assistance is warranted.

In reviewing an Ake claim like Hightower's, we

look to the reasonableness of the trial judge's action at the time

he took it. This assessment necessarily turns on the sufficiency of

the petitioner's explanation as to why he needed an expert. That is,

having heard petitioner's explanation, should the trial judge have

concluded that unless he granted his request petitioner would likely

be denied an adequate opportunity fairly to confront the State's

case and to present his defense? Id. at 710.

The sources available to the trial court in

considering Hightower's request for psychiatric assistance included

(1) written motions and exhibits, (2) defense counsel's

representations at pretrial proceedings, and (3) Hightower's

behavior at pretrial proceedings. We “[place] ourselves in the shoes

of the trial judge [and] analyze the information he received as it

was brought before him.” Messer v. Kemp, 831 F.2d 946, 961 (11th

Cir.1987) (en banc). In so doing, we conclude that Hightower failed

to satisfy his preliminary burden under Ake, and was therefore not

entitled to the services of a psychiatrist.

Hightower's attorneys first notified the trial

court of their desire for expert psychiatric assistance in a written

motion dated August 6, 1987. The full text of the motion reads as

follows:

Motion for Funds to Hire Independent

Psychiatrists

1. The defendant, John Hightower, was arrested on

July 10, 1987, and charged with three counts of Murder.

2. The said Defendant was indicted by the Baldwin

County Grand Jury on July 14, 1987, for said offenses.

3. The District Attorney of Baldwin County,

Georgia, Mr. Joseph Briley, has announced that he intends to seek

the death penalty in the prosecution of said case.

4. Counsel for Defendant feel that the

defendant's mental state, together with the presence or absence of

any mental disorder or disease, may be of importance in the defense

of said action.

5. Defense counsel were appointed by this

Honorable Court to represent the Defendant, the said Defendant

having been found previously indigent by this Court.

6. Defendant is without sufficient funds of any

kind with which to hire independent psychiatric or psychological

experts, and feels that the same would be needed in order to insure

him all of his due process rights under the Georgia and the United

States Constitutions.

7. Defendant believes that independent

psychiatric and/or psychological evaluations need to be accomplished

in order to assure that any and all defenses can be properly

presented at trial.

Wherefore, Defendant prays that funds be provided

to his counsel of record for the purpose of employing independent

psychiatric and/or psychological experts in the defense of his case.

This 6th day of August, 1987.

/s/ Hulane E. George, Attorney for Defendant

B. Carl Buice, Attorney for Defendant

The court heard arguments on this and other

motions at a hearing on August 31, 1987. At the hearing, the court

asked defense counsel whether they intended to “make a motion for an

examination at Central State Hospital.” They answered in the

negative, and asked that the court consider instead their motion for

funds to hire an independent psychiatrist.

The court, pursuant to

Ake, ordered counsel to make a preliminary showing that Hightower's

sanity at the time of the offense was likely to be a significant

factor at trial. Carl Buice, one of Hightower's two attorneys,FN8

offered the following:

FN8. The court initially appointed Alan Thrower

to represent Hightower. On July 17, 1987, 5 days after the murders,

the court granted Thrower's motion to be relieved as counsel due to

a conflict of interest. Four days after granting the motion, the

court appointed Hulane E. George and B. Carl Buice to represent

Hightower. George and Buice were a married couple who were also law

partners. They served as Hightower's counsel both at trial and on

direct appeal.

May it please the Court. Where we are at this

point in this issue is at a very preliminary threshold because if we

were not there we would get into a very circuitous situation.

Obviously in order to determine clearly what we are going to need in

the way of psychiatric testimony we need the help of a psychiatrist.

It is not possible to evaluate fully the mental condition of the

defendant without professional assistance to assist us in doing that

and if the Court would note, the Ake decision does not just have to

do with the defense of insanity, but goes on to talk about whether

the mental condition of the defendant is going to be a factor at the

trial of the case which has to do not only with the guilt/innocence

phase or any plea of not guilty or of guilty but insane or not

guilty for reasons of insanity, but also in the area of litigation

and extenuation in terms of whether there are any characteristics of

the defendant which would be mitigating of the circumstances in the

event that he was convicted.

Now, the only thing we can present to the Court

at this point in the absence of having expert testimony is that

which is already apparent in the record. That is, that we have here

a man who is charged with three murders, the murder of his wife and

two stepdaughters. This comes in a situation in a life history in

which there has been no previous violence. We have a situation where

a person of no demonstrated erratic behavior performs an act which

is in and of itself according to the charge of the district attorney,

stunningly abhorrent.

The event itself, the facts themselves raise the

question of the mental state of the defendant and the circumstances

which would lead up to such an event, not just in terms of insanity

which, of course, is a legal term and not a mental health term, but

in terms of all the factors in the defendant's psyche which might

relate to this event and be important in the defense of his case,

not only in the defense in the guilt and innocence phase, but in any

phase of the trial in extenuation and mitigation.

So, what we are asking for at this point in

regard to this particular thing is some preliminary funds for a

psychiatric evaluation on the part of a psychiatrist who is a part

of the defense team who has-to whom we have access and with whom we

can consult in the building of our defense of this man so that we

can know what further issue we may need to raise in terms of

psychiatric evaluation, what defenses we need to file in terms of

this man's condition, whether we have defenses which are defenses in

the guilt/innocence phase or are just issues in the extenuation or

sentencing phase.

All of these are matters that we cannot determine

without having the benefit of counsel from a competent psychiatrist,

someone trained in the mental health field who can help us know what

to look for in terms of this man's personality. This is no small

issue in a case of this nature.

The mental state of the defendant is going to be

a key factor all the way through and if we are to provide him with

an adequate defense, if we are to be able to raise the issues which

need to be raised in this case or at least consider the issues which

may need to be raised, we need that expert assistance ab initio from

the very beginning.

To make us-to require us to make a showing in

terms of some professional evidence in the case where we have no

authority to get a professional to develop the evidence and have no

resource to a professional to determine what sort of issues may be

available to us, denies us of access to that whole area of defense

from the very beginning.

In response to this statement, the court asked

Buice how much money they needed for a psychiatric expert. He said

they needed $750 “[o]n a preliminary basis, reserving the right to

ask for an additional amount in terms of what we may find as we go

forward.” The court granted the motion and “authorize[d] [counsel]

to expend up to” $750. The court also left open the possibility of

granting more funds in the future, but only after another hearing.

At this point, the prosecutor moved that

Hightower be admitted to Central State Hospital for a “psychological

evaluation,” so that the State could rebut any “claim as to mental

incompetency” that the defense might raise at either phase of the

trial. Defense counsel opposed the motion, stating that they would

have Hightower evaluated by his own psychiatrist.

The court asked

when counsel intended to have Hightower examined by their

psychiatrist. They said they planned to have him examined that very

week. Buice, presumably referring to a psychiatric expert he had

already contacted, added: “He has already done some preliminary

interviews. He is in the process.”

In response to the prosecutor's protests that the

defense was merely seeking to “sandbag” the State by preventing it

the opportunity to examine Hightower, the court purported to grant

the prosecutor's motion. But given defense counsel's representation

that Hightower would soon be evaluated by his own expert, the court

delayed his transportation to Central State Hospital for two weeks.

We now place ourselves in the position of the

trial court and evaluate the evidence as it was submitted. In doing

so, we make several observations. First, defense counsel made no

issue of Hightower's “present sanity,” i.e., his competency to stand

trial.FN9 They opposed the prosecutor's attempt to have Hightower

evaluated by a state psychiatrist, and from the record, it does not

appear that the State ever had him evaluated.

Second, by the time of the hearing, his lawyers

had engaged the services of an unnamed mental health expert, and

this expert had already done some unspecified “preliminary” work on

the case.

Third, presumably because they had already chosen

their own expert, counsel requested only that the trial court grant

them funds. They never raised the option of an appointed

psychiatrist.

Fourth, unlike in Ake, in which the trial court

was so concerned about the defendant's peculiar behavior that he

ordered a psychiatric examination sua sponte, neither the court, the

prosecutor, nor defense counsel ever made an issue of Hightower's

behavior at the hearing.FN10

Fifth, defense counsel failed to offer any fact

bearing upon Hightower's mental status apart from the mere

occurrence of the crime itself. At the hearing, they merely pointed

out that Hightower was accused of three “abhorrent” murders even

though his behavior had never before been violent or “erratic.”

FN9. Nothing in the record indicates that

Hightower's behavior at this hearing was in any way peculiar. Indeed,

Hightower's competency to stand trial does not appear ever to have

been at issue, a point that Hightower himself makes in his brief.

FN10. Nor has Hightower argued to us on appeal

that his behavior should have given the trial court pause.

Based upon these observations, we conclude that

Hightower had at this stage failed to satisfy his preliminary burden

under Ake. The trial court had no evidence upon which to conclude

that his “sanity at the time of the offense [was] to be a

significant factor at trial.” Ake, 470 U.S. at 83, 105 S.Ct. at

1096. Despite this, the court gave his attorneys precisely the sum

they requested for a psychiatric expert. No constitutional error had

yet occurred.

As far as the record discloses, it was not until

some three months later that the trial court dealt in any way with

defense counsel's requests for expert psychiatric assistance. In an

order dated November 25, 1987, the court, citing its authorization

of $750 for the payment of a psychiatric expert, ordered the county

to pay $440 to Dr. N. Archer Moore.

Attached to the order is an

itemized billing record detailing services Dr. Moore rendered in

Hightower's case, which were as follows: (1) a one-hour interview

with Hightower on August 25, 1987; (2) a two-hour interview with

Hightower on August 28, 1987; (3) a two-hour interview with

Hightower on August 31, 1987; (4) a one-hour interview with

Hightower on November 16, 1987; and (5) a two-hour conference with

Hightower's attorneys on November 17, 1987.

At this point, the court could discern the

following. First, defense counsel had taken a portion of the funds

they had received and used it to employ an expert of their choice,

Dr. Moore. Second, Dr. Moore was a psychologist, not a

psychiatrist.FN11 Third, Dr. Moore had taken the opportunity to

evaluate Hightower on four separate occasions for a total of six

hours. Fourth, defense counsel had not yet exhausted the $750 that

they had received for the specific purpose of hiring a psychiatric

expert.

FN11. The November 25 order does not identify

this fact, though Dr. Moore's attached billing statement (1) recited

his professional name as “N. Archer Moore, Ph.D.,” (2) gave no

indication that Dr. Moore possessed a medical degree in addition to

his Ph.D., and (3) listed a single professional affiliation, the

American Board of Psychology. The court from these facts alone could

have assumed that Dr. Moore was a psychologist.

No additional funds were requested at this stage,

and no error had yet occurred.

Another three months passed before defense

counsel presented the trial court with any additional information

regarding a need for expert psychiatric assistance. On February 8,

1988, they filed a motion, which reads as follows:

Motion for Additional Funds to Hire

Psychiatrist

1. On August 31, 1987, this Court granted the

Defendant the sum of Seven Hundred Fifty ($750.00) [sic] to hire a

psychologist and/or psychiatrist to evaluate the Defendant herein.

2. Defendant's counsels retained Dr. Archer Moore,

of Macon, Georgia, to evaluate the Defendant. On the advise [sic] of

Dr. Moore, Defendant's counsels were advised to seek a psychologist

or psychiatrist who had extensive experience in dealing with family

violence to evaluate the Defendant.

3. Dr. Emanuel Tanay, M.D., has been contacted by

Defendant's counsel and has advised us that he would be able to

provide forensic psychiatric services to Defendant. A copy of a

letter from Dr. Tanay and a copy of his vitae is attached hereto as

Exhibit “A” and is made a part hereof by reference.

4. Defendant requires the services of Dr. Tanay,

if he is to adequately present not only his defense but to assist

Defense counsel in the preparation of Defendant's case in the guilt/innocence

phase as well as in the sentencing phase. To deny these services is

to violate Defendant's constitutional rights under the Constitutions

of the United States and the State of Georgia.

WHEREFORE, Defendant herein moves that this Court

order that Dr. Tanay [sic] services be ordered and that this Court

sign an order providing that his services would be reimbursed up to

Six Thousand ($6,000.00) Dollars.

This 8th Day of February, 1988.

/s/ Hulane E. George

B. Carl Buice

The first attachment to the motion was a letter

to defense counsel from Dr. Emanuel Tanay, M.D., dated February 1,

1988. In this letter, Dr. Tanay, writing in response to an

“extensive telephone conference” with defense counsel, expressed his

willingness “to provide forensic psychiatric services” for Hightower

at a reduced rate of $150.00 per hour plus expenses.

Dr. Tanay

estimated that his evaluation of Hightower would take at least

twenty hours, and said that he required a court order to guarantee

that he would be paid on an hourly basis for his testimony. In

closing, Dr. Tanay stated that he could not evaluate Hightower

before April 11, 1988.FN12

FN12. Although it does not appear that a trial

date had yet been set, the court and the parties seemed at that

point to have contemplated a trial in mid- to late-April 1988.

The second attachment to the motion was Dr.

Tanay's curriculum vitae. It showed, among other things, that Dr.

Tanay was a psychiatrist licensed in Michigan, Ohio, and Georgia,

and that he was certified by the American Board of Psychiatry and

Neurology and by the American Board of Forensic Psychiatry. In

addition, the curriculum vitae listed Dr. Tanay's numerous

publications, some of which appeared by their titles to address

legal issues related to insanity, mental illness, forensic

psychiatry, and psychic trauma.

The trial court held a hearing on defense

counsel's motion on February 9, 1988. At the hearing, counsel

informed the court of the following:

We have had Mr. Hightower evaluated by our

psychiatrist, Dr. Archer Moore, and he advised us that we really

needed someone who was an expert in family violence. And we have

combed the United States, and we have been advised that this man-if

you will look at his eight page vitae which is just a part of his

vitae, you can see he is very well qualified. I spoke to Dr. Tanay

and as he said in his letter, he could not evaluate Mr. Hightower

until April the 11th of 1988, and he states that he will reduce his

regular fee to $150 per hour plus expenses. His expenses includes

[sic] coming from Detroit to Atlanta and renting a car. I figure

probably somewhere around $6,000 for total expenses for Dr. Tanay.

We desperately need his input in this case. We need it not only in

the guilt-innocent phase but we need it in the sentencing phase. We

need someone to evaluate Mr. Hightower and to give us some clues as

to the causes of this tragedy. And he seems-according to everyone

that we can talk to-is just about the only one in the United States

that is available.

The prosecutor responded that the court had “bent

over backwards already” in meeting Hightower's requests for

psychiatric assistance, and had “gone further than Ake ” required in

this regard. Defense counsel answered:

We are not asking or dealing with the issue of

minimum requirement of the appellate courts. We're asking for

substantial justice on the part of Mr. Hightower. To use just an

ordinary psychologist in a case of this sort where the issues of

domestic violence, a very specialized field, are at stake is rather

analagous [sic] to using a general practitioner for brain surgery.

If any accused person in Mr. Hightower's situation, who had the

funds to do so, were in his place, certainly a specialist of this

sort would be used.

The only reason for not using a specialist of

this sort in this sort of case would be a lack of funds. And if Mr.

Hightower is therefore refused-denied the access to this sort of

specialist simply because of lack of funds, we submit that it would

be tantamount to a failure of due process.

The court then asked counsel if they could cite

any authority that required the provision of additional funds. They

could not. Instead, they reminded the court that they had received

$750 at the last hearing, and that, as they understood it, they were

entitled to come to the court again “if [they] needed more.” The

court then asked counsel how much money it had given them “to spend

at [their] discretion.” Counsel answered:

We have $5,000-$5,750. And we've divided that

into Dr. Moore's bill which was I think $450 which has been paid. We

had-we have hired a jury specialist and we have hired a special

investigator and that will wipe out all of that money. Without

further argument, the court denied the motion for additional funds.

FN13

FN13. Again, we note that the record bears no

indication that Hightower's behavior at this hearing was in any way

peculiar.

We pause once again to consider whether the court

committed error at this stage. We evaluate the additional evidence

now available to the court and discern how it should have affected

its actions. Several things are worth noting.

First, the court knew nothing of Dr. Moore's

evaluation of Hightower save the dates and durations of the

interviews. It was unclear at this point as to (1) whether Dr. Moore

had been able to diagnose Hightower, (2) why Dr. Moore had “advised”

defense counsel to seek an expert in “family violence,” and (3)

whether and in what phase defense counsel intended that Dr. Moore

testify at trial.

Second, the court knew nothing about the probable

value of Dr. Tanay's assistance. It knew only that (1) Dr. Tanay,

unlike Dr. Moore, was a psychiatrist, and (2) defense counsel

perceived Dr. Tanay to be an expert in the unexplained field of

“family violence.” Defense counsel made no issue of the former

distinction,FN14 but instead grasped upon the latter distinction

without explaining its significance.

The most the court could glean

from counsel's representations was that “family violence” was a

“specialty” of psychology or psychiatry dealing with violent

behavior in the context of family relationships. While a specialist

of this kind might have been useful to Hightower, his attorneys

essentially conceded at the hearing that their own notions of “justice,”

rather than the requirements of law, demanded the provision of such

an expert.

FN14. Because we hold that Hightower had no right

to an expert under Ake, we need not decide the question of whether a

criminal defendant's Ake rights are satisfied by the provision of a

psychologist rather than a psychiatrist.

Third, defense counsel provided no additional

facts upon which to make an issue of Hightower's mental state.

Indeed, although Dr. Moore had evaluated Hightower months beforehand,

counsel still did not indicate that they would offer an insanity

defense at trial.

Fourth, Hightower had not behaved peculiarly at

any proceeding. Based upon these observations, we conclude that

Hightower still had not satisfied his preliminary burden under Ake.

Months after they made their initial request for funds for a

psychiatric expert, defense counsel still had not shown the court

that Hightower's sanity was likely to be an issue at trial. That

they had received expert funds in spite of this deficiency did not

entitle them to more. No error had yet occurred.

* * *

We have surveyed all pretrial proceedings at

which Hightower presented the trial court with information bearing

upon his need for a psychiatric expert. He has failed to identify

any point in those proceedings at which the court, given the

evidence then available, acted contrary to the requirements of

federal law.

We are not unconcerned about putting the

proverbial cart before the horse in cases of this kind. Without

question, defense counsel may be unable fully to understand and

explain his client's mental state until an evaluation is performed.

But Ake does not require defense counsel to guide the trial court

through the depths of the defendant's psyche; all it requires is a

minimum threshold showing that the defendant's sanity at the time of

the offense is likely to matter at trial. No such showing was made

in this case.

Even if we assume that Hightower made the showing

Ake requires, we hold that the trial court met its constitutional

obligation under Ake by providing Hightower with defense funds that

could have been spent on the services of a psychiatric expert.

In addition to the $750 it granted specifically

for a psychiatric expert, the court gave Hightower a lump sum of

$5,000 for defense expenses. In Hightower's view, it would have been

improper under the circumstances for his lawyers to use any portion

of this lump sum for a psychiatric expert.

The Georgia Supreme Court

decided to the contrary on direct appeal, finding instead that

Hightower could have used this lump sum “for a special investigator

or other such expert assistance as [he] might choose.” Hightower v.

State, 259 Ga. 770, 386 S.E.2d 509, 511 (1989). This finding of fact

is entitled to a presumption of correctness, one that Hightower can

rebut only “by clear and convincing evidence.” 28 U.S.C. §

2254(e)(1).

* * *

We turn finally to Hightower's claims of

ineffective assistance of counsel.FN53 Hightower contends that his

attorneys committed various errors at both phases of his trial and

on direct appeal.

FN53. We affirm without further discussion the

district court's rejection of the following 2 claims of ineffective

assistance: (1) that trial counsel failed fully to investigate

Hightower's case, develop mitigating evidence, and seek correct jury

instructions; (2) that trial counsel distanced themselves from

Hightower in front of the jury.

The governing standard is that of Strickland v.

Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 2064, 80 L.Ed.2d 674

(1984):

A convicted defendant's claim that counsel's

assistance was so defective as to require reversal of a conviction

or death sentence has two components. First, the defendant must show

that counsel's performance was deficient. This requires showing that

counsel made errors so serious that counsel was not functioning as

the “counsel” guaranteed the defendant by the Sixth Amendment.

Second, the defendant must show that the deficient performance

prejudiced the defense. This requires showing that counsel's errors

were so serious as to deprive the defendant of a fair trial, a trial

whose result is reliable.

Counsel's performance is constitutionally

“deficient” when it “[falls] below an objective standard of

reasonableness.” Id. at 688, 104 S.Ct. at 2064. We must avoid all

temptation to “second-guess” counsel's decisions as to trial

strategy. Id. at 689, 104 S.Ct. at 2065. Instead, we are to examine

“the facts of the particular case, viewed as of the time of

counsel's conduct.” Id. at 690, 104 S.Ct. at 2066.

To establish prejudice, Hightower “ must show

that there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's

unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been

different.” Id. at 694, 104 S.Ct. at 2068. Put another way, he must

establish that counsel's errors “undermine confidence in the outcome”

of the case.FN54 Id.

FN54. The Strickland Court articulated different

standards for challenges to convictions and sentences:

When a defendant challenges a conviction, the

question is whether there is a reasonable probability that, absent [counsel's]

errors, the factfinder would have had a reasonable doubt respecting

guilt. When a defendant challenges a death sentence ... the question

is whether there is a reasonable probability that, absent the errors,

the sentencer-including an appellate court, to the extent it

independently reweighs the evidence-would have concluded that the

balance of aggravating and mitigating circumstances did not warrant

death. 466 U.S. at 695, 104 S.Ct. at 2068-69.

Although Hightower claims that his attorneys were

ineffective at both phases of his trial and on direct appeal, he

does not clearly differentiate between errors that affected the

guilt determinations and errors that affected the sentences. This

differentiation is of no consequence, as we reject each of

Hightower's claims of ineffective assistance as to both phases of

his trial and as to his direct appeal.

Ineffectiveness of counsel is a mixed question of

law and fact. Id. at 698, 104 S.Ct. at 2070. Thus, we review these

claims de novo. Chandler v. United States, 218 F.3d 1305, 1312 (11th

Cir.2000).

Hightower first argues that his counsel failed to

maintain a coherent defense theory.FN55 We find no basis upon which

to grant relief here.

FN55. Relatedly, Hightower claims that trial

counsel were ineffective for failing to present the testimony of a

“competent” psychiatrist.

In Part III, we hold that Hightower was not

entitled under Ake to the assistance of a psychiatrist, but that in

the alternative, even if he was so entitled, trial counsel received

funds they could have used for a psychiatric expert. Hightower's

ineffective assistance claim depends upon the second alternative.

He states the issue succinctly in a footnote in his brief: “If the

funds provided by the state court were adequate, then trial counsel

should have spent them to hire the qualified psychiatrist they knew

was crucial to their defense.” Essentially, Hightower challenges the

way in which counsel spent the $5,750 in defense funds the court

granted.

We conclude that Hightower has failed to

establish Strickland deficiency in counsel's performance. Apart from

blanket assertions that counsel should have spent some money on a

psychiatrist, he gives no specific indication as to how they should

have acted differently. He does not specify, for example, (1) how

much counsel should have used for a “competent” psychiatrist; (2)

whose services counsel should have declined to employ in order to

retain a “competent” psychiatrist, e.g., the investigator, the jury

specialist, or Dr. Albrecht, all of whom were paid out of the

provided funds; or (3) whether counsel should have hired a

psychiatrist in addition to, or instead of, Drs. Moore and Albrecht,

the psychologists who testified at trial. Because he has failed to

demonstrate with specificity how counsel erred in spending the funds,

Hightower essentially asks us, in direct contravention of Strickland,

to apply the benefit of hindsight to scrutinize counsel's spending

decisions. 466 U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. at 2065. This we will not do.

Counsel testified at the hearing before the state

habeas court that their strategy was to save Hightower's life,

rather than to seek an acquittal. This was a reasonable strategic

choice, given that Hightower confessed to the murders on the same

day they occurred. Counsel only pursued this sentence-focused

strategy after discussing it with Hightower and gaining his

approval. Hightower has failed to articulate any concrete attorney

error that prejudiced his defense.FN56 This claim must therefore

fail.

FN56. Hightower contends that his attorneys

prejudicially altered their theory of defense during the course of

the trial. He points to the fact that counsel accepted a “guilty,

but mentally ill” instruction at the guilt phase charge conference

after initially opposing such an instruction. But we cannot see how

Hightower suffered prejudice in this regard. Reasonably believing

that a “not guilty” verdict was unlikely, counsel evidently felt

that it was to Hightower's benefit for the jury to have an

alternative to straight “guilty” verdicts. That the jury did not

select this alternative is immaterial to a claim of ineffective

assistance of counsel.

We must clarify that this ineffective assistance

claim is wholly separate from a claim that Hightower raised in the

state habeas court and the district court. Before those courts, he

claimed that the trial judge erred by failing to give to the jury

the complete “guilty, but mentally ill” instruction required by

O.C.G.A. § 17-7-131(b)(3)(B). Both courts found this claim

procedurally defaulted.

The question before us is merely whether

trial counsel were ineffective in not objecting to a “guilty, but

mentally ill” instruction in the first instance. We conclude that

they were not. As to the next question, i.e., whether the trial

judge erred in giving an improper “guilty, but mentally ill”

instruction, Hightower has not presented the question to us, and we

therefore do not address it.

Hightower next claims that his attorneys were

ineffective at trial for failing to challenge for cause or

peremptorily strike two jurors who, in his view, appeared

predisposed toward a death sentence.FN57 He also contends that

defense counsel were ineffective on direct appeal for failing to

enumerate as error the court's seating of these jurors. The district

court found that even though counsel may have been deficient,

Hightower failed to establish prejudice resulting therefrom. We

agree.

FN57. Hightower also contends that counsel were

ineffective at trial and on direct appeal because of their ignorance

of the correct standard, i.e., Adams- Witt instead of Wainwright.

See Part V. So stated, this claim misses the mark. Hightower cannot

prevail on a claim of ineffective assistance without showing that he

suffered prejudice. As to a reverse- Witherspoon-based claim of

ineffective assistance, Hightower must show that counsel's ignorance

of the correct standard resulted in the seating of jurors who were

unconstitutionally biased in favor of death.

Practically speaking, Hightower must show that

because of their ignorance, defense counsel failed properly to deal

with these unacceptable jurors, whether by neglecting to (1)

challenge them for cause, (2) strike them peremptorily, or (3) claim

on direct appeal that the trial judge erred by seating them. As with

Hightower's main Witherspoon claims, we examine this ineffective

assistance claim in a juror-specific manner.

We first consider his claim as to juror Paul

Jensen. The relevant portion of defense counsel's voir dire of

Jensen, i.e., that which revealed his attitude toward a death

sentence, reads as follows: MR. BUICE: Mr. Jensen? Where are you on

that? Would the fact that three people died ...? MR. JENSEN: He's

convicted of three murders? MR. BUICE: Yes. MR. JENSEN: It would be

very-it would determine-it [sic] would have to determine the case-the

case would have to determine how I'd feel exactly, but it would be

very hard for me not to vote for the death penalty because of three

murders. MR. BUICE: Well, would the fact of three murders, then,

tend to close your mind to other considerations? MR. JENSEN: Right

now it would, but it would have to be determined by the severity of

the case and what was involved in determining of the three murders.

Counsel challenged Jensen for cause on the

grounds that (1) he was a college student whose worry about missed

coursework would divert his attention, and (2) he appeared to favor

a death sentence if drugs or alcohol had contributed to the

commission of the crime. The court rejected the challenge.

We conclude that this brief voir dire exchange

provides no basis for relief. FN58 Although Jensen suggested that he

would favor a death sentence if three murders were established, he

also indicated that he could not form an opinion on the sentences

until he heard the evidence.

Given the difficulty of reviewing such

equivocal answers from the cold record, years after they were

uttered, it is obvious why we accord great deference to trial judge

determinations of juror bias. See, e.g., Wainwright v. Witt, 469

U.S. 412, 429-30, 105 S.Ct. 844, 855, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985) (holding

that a trial court's determination of juror bias is a matter of

fact, to be reviewed as such under 28 U.S.C. § 2254).

The trial judge, in a superior position to

observe Jensen's credibility and demeanor, refused to excuse Jensen

for bias. We cannot say that Hightower suffered prejudice from

counsel's failure to strike Jensen peremptorily or to allege on

direct appeal that the court erred in seating him.

FN58. In support of his claim, Hightower offers

no evidence beyond the excerpted portion of Jensen's responses that

we reproduce here.

We next consider Hightower's claim as to juror

Rufus Little. Defense counsel's voir dire of Little proceeded as

follows: MS. GEORGE: ... I am going to again ask the same question

and I am going to say this with two questions. If a person has been

convicted of murder and the murder of three people, are you strongly

in favor, somewhat in favor, or somewhat opposed to the death

penalty? ... Okay, Mr. Little? MR. LITTLE: Strongly for it if it has

been proven. MS. GEORGE: If it's been proven? MR. LITTLE: Yes. ...

MS. GEORGE: If there were a conviction of three deaths [sic], three

people involved, three people had died, could you vote for a life

imprisonment, would that be severe enough punishment for you? ...

How about you, Mr. Little? MR. LITTLE: I would have to hear the

case. Three murders, you know, that's cruel, but there may be

something out of it to prove without a doubt, well then a life would-I'd

have to hear the case. ... MS. GEORGE: All right. How about you, Mr.

Little? Would you automatically vote for the death penalty if there

was a conviction of three people? MR. LITTLE: If they proved without

a doubt he did it. MS. GEORGE: You would automatically do it? MR.

LITTLE: If they proved without any doubt, based on the circumstances,

I would. But it's hard to say until I hear the whole case. MS.

GEORGE: But you did say if the person was convicted beyond a

reasonable doubt, you would automatically vote for the death penalty?

MR. LITTLE: Automatically-like I say I would automatically-like I

say I would have to hear the case. Like I say I would automatically

vote for the ... MS. GEORGE: That's all I have Your Honor.

Counsel did not (1) challenge Little for cause,

(2) exercise a peremptory strike against him, or (3) claim on direct

appeal that it was error to seat him. Again forced to review the

cold record to detect bias,FN59 we decline to grant relief. In our

view, Little's statements during voir dire, in their totality, do

not reflect a pro-death sentiment sufficient to establish prejudice.

Even as defense counsel sought to pin down his bias, Little

continually expressed that he would need to hear the whole case

before deciding on the proper punishment. We agree with the district

court that Hightower failed to show that Little's views on the death

penalty “would prevent or substantially impair the performance of

his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his

oath.” Id. at 424, 105 S.Ct. at 852.

FN59. Hightower produces no evidence as to Little

beyond this excerpt of his examination.

We have considered Hightower's claims and find

them to be without merit. The judgment of the district court is,

accordingly,

AFFIRMED.