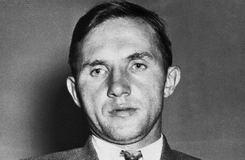

JOHN F. TYRRELL, Sworn as a witness in behalf of the

State:

Direct examination by Mr. Lanigan:

Q. Where do you reside, Mr. Tyrrell?

A. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Q. Your occupation?

A. Examiner of questioned documents.

Q. Have you testified on the subject of questioned documents in court?

A. I have.

Q. What part of your time do you devote to the work of examining

questioned documents?

A. My entire working hours.

Q. Describe briefly what work you have done and what studies you have

pursued in connection with the subject.

A. I have examined documents, signatures, writings and the like for

forty years. I have a library of the best books which I have read. I

have an equipment of the approved cameras, instruments, and various

matters necessary to conduct the examination of documents.

Q. Can you recall some of the cases in which you have testified?

A. I testified in the Molineaux case in New York City 35 years ago, the

Rice-Patrick case, Dr. Kennedy case – those are homicide cases. I

testified in the McCormick case, Magniesen case, and other homicide

cases and in the Leopold and Loeb case in Chicago.

Q. Now, Mr. Tyrrell, I show you the ransom notes and ask you if you

made an examination of those?

A. Yes.

Q. I show you the request and conceded writings and ask if you have

made an examination of those.

A. Yes.

Q. In addition have you made an examination of any other documents of

Bruno Richard Hauptmann which are evidence in this case?

A. Yes.

Q. What other documents, please?

A. Documents having to do with automobile licenses.

Q. What was the purpose of your examination, sir?

A. To determine whether or not there was an identity existing between

the normal or automobile writings, the request writings and the ransom

notes.

Q. As the result of your examination and comparison, have you reached

an opinion concerning them?

A. Yes.

Q. Are you prepared to express it?

A. Yes.

Q. What is that opinion?

A. That the writers are identical, that they are all written by the one

writer.

Q. Now, have you prepared any illustrations?

A. Yes. I have here a number of comparisons made by placing together in

columns words and characters taken from the three writings referred to.

They are photographic reproductions of the writings.

Q. Now, Mr. Tyrrell, proceed with your illustration.

A. "The boy is on the boat Nellie"; and I find evidence that in my

opinion points to one writer of the series. The first note, the cradle

note, is somewhat of an extravagant disguise. This is evidenced by the

inconsistencies as shown by some of the words and letters and others.

This similar or a similar disguise is shown in the first four lines of

the second note. Obviously the writer of the second note did not have

the first note before him when the second note was written. But there

are in those first four lines, as it were, recollections of the writing

of the first note, in the letter "y", for instance.

Q. Will you illustrate it, please?

A. The "y" is first made as a "v" and then a stroke is added to it to

bring it off to the side. Now that is a peculiar way of making a "y" and

is shown in the word "baby" of the second note. Now these y's of the

ransom notes, you will notice some variation, but there is this

distinctive feature in them, and that is that the upper part is made

like a "V" with a sharp turn at the bottom, and this type of "Y" is

prevalent throughout these writings. Sometimes the after part of this

"V" is made in the same line or direction as the finishing stroke. But

the y's, their idea of form, their execution, is the same, and there is

with these that variation which is an actual variation, that is, that a

writer does not always write exactly alike although he may intend to;

but he follows his practice and we do not always precisely duplicate the

letters that we make.

There is a strong identity in these y's and this, with the other

matters that I have referred to, I regard as one writer having written

these notes.

Q. Now, Mr. Tyrrell, will you proceed with Exhibit S-123.

A. I had already drawn the word "child" on the chart and referred to

its peculiarities. Now, this dropped part of "h" is a very peculiar

matter in writing. I have not found it in any case that I have ever

examined to the extent shown here. There have been one or two instances

in my experience where part of an "h" has been dropped, but that was

probably in those cases accidentally, as there were but one or two

instances of it.

But in this case it appears to be a habit of this writer to do that

peculiar thing, and these h's are slighted in the ransom notes in

numerous places and also in the writing from dictation, which, in my

opinion indicate that it is an unconscious habit of this writer to do

this peculiar thing. Now we have the word "that" taken from Exhibit

S-65, the sixth line.

Q. Referring to letter of April 1st.

A. And here we have another element introduced and that is that the

"t's" are uncrossed. Of course it is not exactly unusual for a writer to

neglect to cross his t's and I have seen German writers that did it.

That is probably induced by the fact that the German "t" is not made

with a cross as we make it, but by a little turn at the bottom near the

base line, a very expressive and legible letter as they make it, but

this writer makes a turn at the bottom of the "t," a turn of the pen for

the stroke to the next letter and does not cross the "t."

[We also] have five instances of the dropping of the "h" in the

defendant's signature.

Q. Yes?

A. The word "Richard." The "h" is slighted, and that occurs in four of

the request writings signed "Richard Hauptmann"; also in the automobile

card, which in my opinion is an indication that this peculiarity exists

in the handwriting of this writer to the extent that it is even

incorporated in his own signature.

Q. Proceed, please, sir.

A. This word "time" is written in a very angular type of writing, and,

by the way, when these dictated writings are examined, they are two

varieties of writings at least, one is the writing that more resembles

the ransom letters and the other is a very angular and compact type of

writing. The two writings in these dictated writings, if placed side by

side, would hardly pass as being written by the same writer without

close comparison. Pictorially they are dissimilar.

Q. Did you make such a close comparison, Mr. Tyrrell?

A. I did.

Q. And who was the writer, in your opinion?

A. The writer of the standards. All of these converge and point into one

direction.

Q. For the purpose of clarification, when you refer to the standards,

to what writings do you refer?

A. I refer to what might be termed the business writings of Richard Hauptmann, as shown in the [automobile] cards, and the others as the

dictated writings.

[Mr. Tyrrell proceeds to explain his opinion of

similarities between "w's"; "N's"; transposed letters in the ("hte" with

the uncrossed "t's" looking like "l's". With some items, especially

"x's", he ascribes some dissimilarities to "an individualism, and

important to that extent."]

Q. All right. Now, will you resume the witness

stand, please?

A. (Witness resumed the stand from the display easel.)

Q. Now, Mr. Tyrrell, you have examined all of the automobile licenses

of Bruno Richard Hauptmann?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You have examined this Haberland agreement in the handwriting of

Hauptmann?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You have examined all of the ransom notes?

A. Yes.

Q. From your examination and comparison of the conceded writings and

the automobile writings and the contracts of Hauptmann, can you say

positively who wrote the ransom notes?

A. The writer is identical. If the automobile cards and the request

writings were written by Bruno Richard Hauptmann, then he also wrote the

ransom notes.

Q. All of the ransom notes, sir?

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Lanigan: You may cross-examine.

Cross examination by Mr. Pope:

Q. Mr. Tyrrell, how long have you been engaged in

the examination of questioned documents?

A. Well, I started with the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Co –

Q. No, how long?

A. Just a moment. I will explain this. You are getting it.

Q. How many years have you been engaged?

A. The difference between 1883 and 1934.

Q. And how many years have you been engaged in examining what may be

termed disputed handwritings?

A. Well, my first case was in 1892.

Q. Did you ever attend any school or college or institution of learning

for the purpose of qualifying yourself to examine disputed handwritings?

A. No. My college was the experience –

Q. There is no such school or institution of learning that teaches the

art of examining disputed handwritings, is there?

A. No, that I know of.

Q. Now in all of your experience in the examination of disputed

handwritings do you generally find it to be true that the handwriting

which you are examining is disguised or camouflaged?

A. No.

Q. Have you ever examined a case in which there were ransom notes or an

attempted extortion before?

A. Yes, four or five.

Q. And in each one of these cases, did you find evidences of an attempt

to disguise?

A. Yes – quite a decided attempt.

Q. Well, except in forgery cases, do not all disputed handwritings

present an attempt to disguise?

A. No.

Q. You examined the ransom note in this case didn't you, very

carefully?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is there any doubt in your mind that the writer of that note

attempted to disguise his handwriting?

A. No.

Q. Would you say from your examination that it was written with [the]

left hand or the right hand?

A. I couldn't say.

Q. Did you attempt to find out?

A. Of whom would I ask?

Q. From your examination of the handwriting.

A. Writing with the left hand, the legibility –

Q. No, just a minute, Professor.

A. No, just plain Mister.

Q. That is right. Just answer yes or no. It is quite easy for a

handwriting expert to determine when a right hand writer uses his left

hand, isn't it?

A. No.

Q. From the formation of his letters and the general slant and the

shadings?

A. It depends much on the ability of the disguiser.

Q. Well then, if there is no difference presented in the slant and

shading, then there is another attempt to disguise?

A. I don't quite get that.

Q. Where a right hand writer uses his left hand and there appears to be

no natural difference in the shading and in the slant, would you say

that was an additional attempt to disguise?

A. Well, that is only a fragment of a case such as would come to me, I

don't think I could pass upon that.

Q. Well then, you don't get me, so we will drop it.

A. All right.

Q. Did you notice any marked difference between the writing of the

ransom notes and the subsequent notes that were sent to Dr. Condon and

Mr. Lindbergh?

A. Yes. They were less violent in their expressions of words and lines.

Q. From your experience, what other methods of camouflage have you

found used by writers who were trying to pull something over on somebody

– if we may use that expression?

A. I wasn't very successful in discovering where they got their

inspiration.

Q. I am not talking about their inspiration; I am asking you what

method they used to disguise their handwriting or to prevent detection.

A. Well, sometimes they used pen printing. Sometimes they used a

difference in the slant, a difference in pen-holding.

Q. Well, that is the formation of letters. I am asking you if they used

any other method besides the malformation of letters?

A. Yes, they would be likely to use anything that occurred to them that

would destroy a pictorial resemblance to their own writing.

Q. For instance, like a transposition of words?

A. Well, I have found a case or two where there was transposition of

words.

Q. And the use of ungrammatical expressions?

A. That is largely an educational matter.

Q. Well, from your experience, have they sometimes endeavored to ward

off suspicion by the use of ungrammatical expressions?

A. Yes.

Q. Now your examination of the questioned documents is not limited

merely to the examination of the formation of letters, is it? You study

the entire instrument, don't you?

A. Yes.

Q. And particularly where you are trying to connect a series of

documents, you try to connect up one with the other grammatical

expressions and rhetoric which you find here and there, do you?

A. Well, those would come naturally under consideration.

Q. Now, I want to call your attention to S-121, which is your number 1.

In this exhibit, you call attention to the capital D, didn't you?

A. Yes.

Q. I want to call your attention to the capital D's in the ransom note,

as found beginning at the top, No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, in fact, every one

of them, all the way down the line, as compared with the capital D under

the dictated column on the right. There is a dissimilarity there, is

there not?

A. Yes.

Q. Those instances of connection which I have just pointed out are

marked dissimilarities, are they not?

A. Yes.

Q. Now, then, referring to the capital S in the word "Sir" – take the

one at the top, the ransom note. May I have your chalk a minute? I am

not very much of a handwriting expert, but I think perhaps I can help

you a bit.

A. You may be an artist in disguise. I don't know.

Q. Referring to the "S's" in the dictated handwriting, there are five

of them; they are all dissimilar to the ones I have pointed out, are

they not?

A. Yes.

Q. Now in this next exhibit, you called attention to the letter y's. I

call your attention first to the ransom y's and then to the standard

y's. Taken the third word. That looks to me like "notify." That is an

entirely different form of "y", isn't it?

A. Yes.

Q. And then you come to the fourth word "notify." That is still another

form of "y", isn't it?

A. Yes.

Q. I next want to call your attention to S-123. When you were

demonstrating this exhibit, you laid great stress upon the small "d" in

the word "child", didn't you?

A. Yes.

Q. And in the dictated letters you found a copy of the ransom letter,

didn't you?

A. No, I don't recall.

Q. You don't recall?

A. No, I used this illustration for a different purpose.

Q. Yes. But at any rate if you found the word "child" in any of the

dictated writings, you did not show it up on your photograph here?

A. No.

Q. Or use it for comparison?

A. This chart was used to illustrate the dropping of one part of the

letter "h".

Q. And also the peculiar character of the letter "d"?

A. Well, I referred to that, but the chart itself wasn't arranged with

that purpose in mind.

Q. I see. But the one thing that you desire the jury to pay attention

to is the formation of the letter "d" in "child".

A. Yes.

Q. You illustrated that on the chart, didn't you?

A. Yes.

Q. Now referring to the other word "Richard" under the heading on your

chart "Standard Writings" in the middle column, every one of those are

dissimilar from the "d" in the word "child", which you expressed, are

they not?

A. Yes.

[Mr. Pope addresses next the "h", comparing the

standard (dictated letters) to various ransom notes, finding an apparent

dissimilarity in the two methods of formation. He follows with like

attention to the "y"/"j" assertion made in the direct examination.]

Q. Now, referring to the "o" in the ransom note, are

they not what you might term wide open "o's" at the top?

A. Yes.

Q. And the "o's" in the dictated writing, while they are open, they are

more closely drawn together, are they not, or closed at the top?

A.

In some instances.

Q. In some instances. I think that finishes with that one, sir....

Q. Then it is your idea from studying these

exhibits that the ransom notes were probably written by a man of German

extraction?

A. Yes.

[Mr. Pope introduces the hyphenation between the words "New" and "York"

as evidenced in both the standard handwriting as well as the dictated

letters.]

Q. In all of your experience you have never seen "New York" written

with a hyphen between "New" and York"?

A. No.

Q. By German writers?

A. No.

[Mr. Pope introduces eight envelopes and post cards, all bearing a

hyphenated "New York".]

Q. You know German writing when you see it?

A. Yes.

Q. You have studied it many, many years.

A. Yes

Q. [In reference to a particular post card's post mark.] I ask you the

plain question, is or is not that German writing?

Mr. Wilentz: Just a moment. I don't want to object, but may I suggest to

the witness that it is not necessary for him to answer that question if

he has not had sufficient time to study it.

Mr. Pope: There are only two words in "New York" – I withdraw the

question.

[Mr. Pope continues with a number more items exhibiting a hyphenated

address.]

Mr. Pope: I think we have enough of these exhibits, haven't we? We have

more here, but I think that is plenty to demonstrate our point.

[Mr. Pope attempts to inject a methodology of reading

the notes "without disguising techniques", using instead the correct,

de-coded, intent of the writer. He tries to work in the view that the

notes have been written by an "... experience good English scholar" and

also a businessman]

Q. Now, I believe you said you came form

Milwaukee?

A. You believe correctly.

Q. Mr. Tyrrell, do you remember about ten years ago being a witness in

– I think it was – the Municipal Court of Milwaukee?

A. Yes.

Q. Whatever it was, in a case brought in an indictment against Gordon

Morgan?

A. Don't recall it.

Q. Who was charged with forging, with allegedly forging a document, in

which you appeared as the handwriting expert for the State.

A. I remember a case of that description.

Q. Yes. Perhaps I can refresh your recollection. The particular

defendant that I am referring to – if I do not happen to have his name

correctly – is this: This man was convicted and sentenced to prison and,

after he was convicted upon your testimony –

Mr. Wilentz: Just a minute.

Q. – a man by the name of Herman Eckert

confessed that he himself had written the checks and the case was

reopened and Morgan was discharged.

Mr. Wilentz: Please don't answer the question until I have a chance to

object.

The Court: Do you remember the case to which I am now referring – you

may answer that, yes or no.

The Witness: Yes.

Q. And in that case you testified that the forged

checks were in the handwriting of the defendant, didn't you?

Mr. Wilentz: Just a minute, I object to the question. This gentleman's

qualifications were admitted and conceded.

The Court: Well, Mr. Attorney General, I am not so sure that that is

exactly so. The qualifications of the preceding expert were expressly

admitted. When I put the question to Mr. Pope he declined to admit the

qualifications of this expert. I considered that he was qualified, but

you see there is a reservation there and apparently he is entitled to

press this question. You may proceed.

(Question repeated by the Reporter.)

A. Yes.

Q. And the defendant was convicted, wasn't he?

A. Yes.

Q. And this man Eckert afterwards confessed that he had forged the

checks?

A. Next day.

Q. I see. That's all.