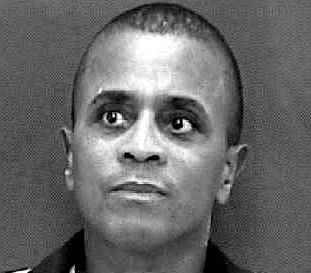

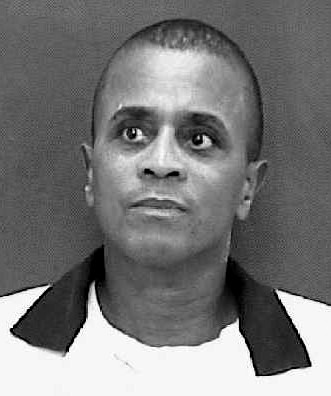

Georgia Attorney General Thurbert E. Baker offers the following information in the case against Willie James Hall, who is currently scheduled to be executed at 7 p.m. on January 27, 2004.

Scheduled Execution

The Superior Court of Dekalb County has filed an order setting the seven-day window in which the execution of Willie James Hall may occur to begin at noon, January 27, 2004 and to end seven days later at noon on February 3, 2004. The Commissioner of the Department of Corrections has set the specific date and time for the execution as 7:00pm on January 27, 2004, pursuant to the discretion given the Commissioner under state law. Hall has concluded his direct appeal, as well as state and federal habeas corpus proceedings.

Hall’s Crimes

The Georgia Supreme Court summarized the facts as follows:

“Bo" Hall and his wife Thelma had a tumultuous marriage. On July 5, 1988, Thelma moved in with a friend, Valeria Hudson. That weekend, Hall was observed by several persons lurking near Hudson's apartment. On Sunday evening, July 10, Hall told his wife's sister that he was looking for Thelma. He stated, "I am gonna kill her," and predicted, "I couldn't get no more than ten years."

On Monday morning, July 11, a 911 operator received a call from Thelma. This call was tape-recorded. The recording was played at trial. Thelma reported that someone was "trying to break in the house." The 911 operator obtained her address and asked her if she knew who it was outside her house. She responded that she did not think so. Immediately afterward, the operator heard the sound of breaking glass and then listened to Thelma Hall's final words: No . . . Stop, stop, stop Bo . . . stop it Stop it, stop it Bo stop it, stop it the police are on the way Please, Bo, quit it Bo, stop Bo, stop it please Bo, stop it Bo, stop, stop it Stop it . . . Please Bo, please stop Stop it Oh God Stop Bo Bo, please, please Bo please Bo, Bo stop Stop Bo please Oh God . . . Oh . . .

The police arrived within minutes and discovered Thelma Hall's body. She had been stabbed 17 times, including a series of stab wounds in a pattern about the neck like a "necklace." Two shoe prints matching the defendant's were found on the scene along with several of his fingerprints.

Hall v. State, 259 Ga. 412, 413, 383 S.E.2d 128 (1989).

The Trial

The Dekalb County Grand Jury indicted Hall for murder, felony murder (2 counts), and burglary. Hall was found guilty as charged on all four counts by a jury in the Superior Court of Dekalb County, Georgia on February 2, 1989. On February 3, 1989, Hall was sentenced to death for the murder convictions, and received 20 years for burglary, to run concurrent with counts 1, 2 and 3.

The Direct Appeal

The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed Hall’s convictions and sentences in Hall v. State, 259 Ga. 412, 413, 383 S.E.2d 128 (1989).

State Habeas Corpus Petition

Hall, represented by Michael Mears, filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the Superior Court of Butts County, Georgia, which was denied, following an evidentiary hearing, on October 20, 1992. The Superior Court of Butts County denied habeas corpus relief on July 27, 1993. The Supreme Court of Georgia subsequently denied an application for a certificate of probable cause to appeal on March 1, 1994.

Federal Habeas Corpus Petition

Hall, represented by Mildred H. Geckler, filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division, on April 23, 1997. Petitioner raised the following issues: 1) Ineffective assistance of counsel; 2) Denied a full and fair hearing in his state habeas proceedings; 3) State used peremptory challenges in a racially discriminatory manner; 4) Trial court erred in refusing to instruct the jury on voluntary manslaughter; 5) State suppressed material exculpatory evidence; 6) Trial court refused to provided Hall with independent expert witnesses to consult with defense counsel regarding evidence offered by the State 7) District Attorney’s improper and prejudicial closing arguments 8) Jurors hid their true beliefs about the meaning of a life sentence, and voted for death because the trail court would not assure them that if they voted for life Hall would remain incarcerated for life 9) Death sentence imposed against Hall is racially biased 10)Trial court erred when it failed to vacate the convictions for felony murder and subsequently presented those counts to the jury for sentencing consideration 11) The use as evidence against him and the publication in open court before the jury of a 911 recording violated his rights 12) The trial court erred in allowing the State to elicit hearsay testimony from key prosecution witnesses 13) The trial court unreasonably restricted counsel’s voir dire 14) Death qualification of jurors violated Hall’s rights 15) Defense counsel was prevented from ascertaining whether prospective jurors would automatically vote to impose the death penalty 16) Improper excusal of prospective jurors for purported scruples against the death penalty 17) Trial court erred in permitting the jury to convict Hall of three counts of murder for one offense 18) Mental illness prevented Hall from accepting advice of counsel and a life plea 19) Cumulative error 20) UAP is unconstitutional 21) Death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment. Petitioner amended the petition on August 15, 1997.

The federal district court granted partial relief as to sentence in Case No. 97-00723-CV on August 15, 2001 and clarified that order again on August 16, 2001.

Appeal to the Eleventh Circuit

Both parties appealed the district court decision to the Eleventh Circuit. The Eleventh Circuit, in its decision of October 25, 2002, denied relief, reversed the decision of the district court, and reinstated Hall's death sentence, Hall v. Head, 310 F.3d 683 (11th Cir. 2002).

Hall filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court on June 9, 2003 without necessary supporting documentation attached. Hall then filed a Corrected Petition for Writ of Certiorari on August 4, 2003. The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari on October 6, 2003.

HALL v. THE STATE.

4415#259 Ga. 412, 4415#383 SE2d 128

Supreme Court of Georgia, (September 11, 1989)

Docket

number: 47019

Tony L. Axam, for appellant.

This is a death penalty case. Willie James (Bo) Hall was convicted of murder and burglary. He was sentenced to death for the murder. We affirm. [1]

"Bo" Hall and his wife Thelma had a tumultuous marriage. On July 5, 1988, Thelma moved in with a friend, Valeria Hudson. That weekend, Hall was observed by several persons lurking near Hudson's apartment. On Sunday evening, July 10, Hall told his wife's sister that he was looking for Thelma. He stated, "I am gonna kill her," and predicted, "I couldn't get no more than ten years."

On Monday morning, July 11, a 911 operator received a call from Thelma. This call was tape-recorded. The recording was played at trial. Thelma reported that someone was "trying to break in the house." The 911 operator obtained her address and asked her if she knew who it was outside her house. She responded that she did not think so. Immediately afterward, the operator heard the sound of breaking glass and then listened to Thelma Hall's final words:

No . . . Stop, stop, stop Bo . . . stop it

Stop it, stop it

Bo stop it, stop it the police are on the way

Please, Bo, quit it

Bo, stop

Bo, stop it please

Bo, stop it

Bo, stop, stop it

Stop it . . .

Please Bo, please stop

Stop it

Oh God

Stop Bo

Bo, please, please

Bo, please

Bo, Bo stop

Stop Bo please

Oh God . . . Oh . . .

The police arrived within minutes and discovered Thelma Hall's body. She had been stabbed 17 times, including a series of stab wounds in a pattern about the neck like a "necklace." Two shoe prints matching the defendant's were found on the scene along with several of his fingerprints.

1. Hall first contends the voir dire examination was overly restrictive. He contends the trial court erred by disallowing defense questions about the recent Ted Bundy execution and about a local radio call-in show dealing with the meaning of the life imprisonment sentence, and contends the court erred by refusing to allow him to ask prospective jurors to specify "a reason" that would warrant a sentence less than death.

There was no error.

The scope of the voir dire examination

is left largely to the discretion of the

trial judge. The examination here was "broad

enough to allow the parties to ascertain

the fairness and impartiality of the

prospective jurors." Curry v. State,

2. During closing argument of the sentencing phase of the trial, the district attorney argued:

You may think of an analogy in certain ways about the way people sometimes felt about DUI's twenty years ago, oh, well, you know, no big deal, we will reduce it down and give a little warning. That's not the way it is anymore. And that is not the way it should be with domestic violence. . . . But let me just ask you to think that perhaps in some way in the future the public may feel somewhat the same about domestic violence as they now do about . . . vehicular homicides. Let us all hope that the public feels that way, and if it deters one person, it is worth it. . . . I am asking you to deliver a message.

Hall contends these remarks impermissibly referred to matters outside of evidence and were an invocation of prosecutorial expertise.

It is not error to

refer during closing argument to matters

" 'within the common knowledge of all

reasonable people.' [Cit.]" Brooks v.

Kemp, 762 F2d 1383, 1408 (11th Cir.

1985). Thus the district attorney's

analogy to DUI cases was not improper.

Nor can it be viewed as an improper

invocation of prosecutorial expertise.

The prosecutor was entitled to impress "upon

the jury the enormity of the offense and

the solemnity of their duty in relation

thereto." Patterson v. State,

3. At the hearing on the motion for new trial, a paralegal for Hall testified that she had interviewed ten of the twelve jurors. She stated that two jurors claimed they had been convinced to change their vote from a sentence of life imprisonment to the death penalty because other jurors in the juror room informed [them] that there was no such thing as life imprisonment without parole."

Hall argues that

there was, in effect, an intentional

gathering of extrajudicial evidence that

was communicated to other jurors, and

that this alleged misconduct falls

within the exception to the rule that

jurors cannot impeach their own verdict.

See Watkins v. State,

In Watkins, two

jurors had conducted an independent,

unauthorized visit to the crime scene,

and had reported their findings to the

other jurors. The state contends that no

such extrajudicial investigation or

communication occurred here, and

contends this case is controlled by

Aguilar v. State,

In Aguilar, three of the jurors gave post-trial affidavits stating

they had believed [the defendant] guilty of voluntary manslaughter, but agreed to a murder conviction because one of the jury stated that voluntary manslaughter probably would not give him enough punishment.

Id. at 831. Aguilar relied unsuccessfully upon Watkins to support his claim of jury misconduct. We disagreed, observing:

What goes on in the jury room is a complicated weighing process, in which the final unanimous verdict is merely the resultant of numerous competing forces. See generally H. Kalven & H. Zeisel, The American Jury (1966). Our statute . . . prohibits the jurors from impeaching their verdicts. . . . The purpose of the statute is plainly to prohibit after-the-fact picking at the negotiating positions of the jurors and of their attempts to persuade one another.

Id. at 832.

The events in this

case do not fall within any exception to

the rule that "affidavits of jurors may

be taken to sustain but not to impeach

their verdict." OCGA

5. The death sentence

was not imposed under the impermissible

influence of passion, prejudice, or

other arbitrary factor. OCGA

APPENDIX.

Jefferson v. State,

Robert E. Wilson, District Attorney, James W. Richter, Eleni Ann Pryles, Assistant District Attorneys, Michael J. Bowers, Attorney General, Andrew S. Ree, for appellee.

Notes:

1. The crime was committed on July 11, 1988. Hall was indicted on September 12, 1988; be was convicted and sentenced to death on February 3, 1989. A motion for new trial was filed February 8, 1989 and denied March 30, 1989. The case was docketed in this court May 4, 1989. Oral arguments were heard June 27, 1989.

2. In view of our holding, it is not necessary that we decide whether, as the state contends, the defendant's evidence was hearsay or whether, as the defendant contends, the state waived any hearsay objection to the testimony of the defendant's paralegal.

Willie James Hall