PETITION FOR EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY

of

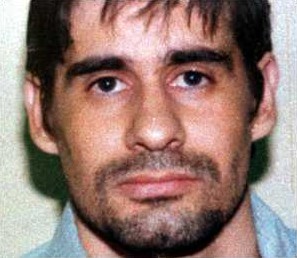

ANGEL FRANCISCO BREARD

INTRODUCTION

Angel Francisco Breard is a Paraguayan citizen on Virginia's Death Row.

He committed a terrible crime which he deeply regrets, and which he

firmly believes, based upon his religious and cultural background, was

caused by a satanic curse placed upon him by his ex-father-in-law.

Raised in the Roman Catholic faith,

Angel was reborn in Jesus Christ early on during the course of his

imprisonment, a redemption which he believes purged him of the satanic

curse.

While the specifics of Angel's

religious beliefs may not be of great importance in terms of the

decision whether to grant him clemency, the effect of those beliefs upon

his character and actions during the course of his imprisonment is.

Angel has become deeply involved with Beth Messiah Congregation, an

evangelical Jewish-Christian group (Jews for Jesus) based in

Gaithersburg, Maryland, and has spoken many times to the radio audience

of Apolstolos y Profetas (Apostles and Prophets) on a program called

Camino al Cielo (the Way to Heaven), which reaches out to people in

prison and hospitals, about his conversion and beliefs.

He participated in Bible study

groups while incarcerated in Arlington, and has studied the Bible with

individual death row prisoners at Mecklenburg in an effort to develop

their and his own spiritual lives. He has authored many writings

proclaiming the word and the love of God and Jesus. See, e.g., Ex. 1. He

has become deeply committed to, and on October

18, 1996, married, a member of his Maryland church congregation, and has

become stepfather to her two children. See Ex. 2.

Affidavits from family and friends

in Paraguay who knew Angel prior to a serious automobile accident which

resulted in damage to the left fronto-temporal region of his brain, the

region associated with discontrol symptoms, especially in conjunction

with the intake of alcohol, see Ex. 3, show that his current conduct is

far closer to his true personality than were the crimes he committed in

1992. See Exs. 4-11. Imprisoned and without access to alcohol, Angel

poses no threat to society, and he in fact serves as a positive

influence in the prison environment. Moreover, he has become an

important force in the spiritual lives of his wife and step-children.

See Ex. 2.

Breard, His Crime and Trial

Angel Breard was born in Argentina, his father's native land, in 1966.

In 1978 his family moved to his mother's family's home in Paraguay, and

Mr. Breard later adopted Paraguayan citizenship. His father died when

Angel was 17. The automobile accident in which Angel suffered injury to

his brain occurred in 1985. In 1986, at the age of 20, he came to the

United States, where he soon found work and began to send money home to

help support his family. Exs. 4; 12, && 23, 156. He married in 1987, but

the marriage lasted less than six months and had a disastrous ending

caused by his father-in-law. Ex. 12, & 17, 22.

In the years following his divorce,

Angel began drinking to excess on a daily basis. In 1992, depressed and

drunk, Angel committed a murder in the course of an attempted rape.

Angel was arrested on September 1,

1992 and charged with capital murder and attempted rape. Id., && 4-7.

Virginia has stipulated that he was not, at the time of his arrest or at

any time thereafter, informed by Virginia or local authorities of his

right pursuant to Article 36 of the Vienna Convention on Consular

Relations, Apr. 24, 1963, 21 U.S.T. 77, 596 U.N.T.S. 261 (the Vienna

Convention or the Convention or the treaty) to contact the Paraguayan

and/or the Argentine consulates for assistance in his defense. Ex. 13.

He did not become aware of that right until his direct appeal and state

habeas corpus proceedings had been concluded.

Prior to trial, the Commonwealth Amade it clear to [Angels attorneys]

that the Commonwealth would forego the death penalty if Mr. Breard would

plead guilty. Affidavit of trial counsel, Ex. 14, & 5. This affidavit

was procured by the Commonwealth and introduced by it against Breard in

his state habeas proceeding. Trial counsel had investigated the

Commonwealths evidence against Mr. Breard and satisfied [themselves]

that the prosecution would be able to prove Breard's guilt beyond a

reasonable doubt. Id., & 4.

Nevertheless, against the advice of

his counsel, Angel refused the offer of a life sentence

and pled not guilty. Unfamiliar with the law and culture of the United

States, he had decided instead to testify and admit his guilty to the

jury in the hope that the jury would set him free upon learning that a

satanic curse, now lifted, had been responsible for the crime. Id., &

16, and attached memorandum.

The Commonwealth's case against

Angel was based entirely on DNA. The prosecution introduced no

incriminating statements. After the prosecution rested, Angel took the

stand in order to confess his crime to the jury. He testified that a

satanic curse had been placed upon him by his former father-in-law, that

the curse had caused him to commit the murder, and that the curse had

been lifted upon his finding Jesus Christ after his arrest.

On direct examination, he described

the curse and his release from it as follows:

A. What I was going through is full

of thought that came to my mind and keep coming to my mind and more than

that, that I know now, is that everything is a spiritual thing, it's --

it's a warfare, it's a bitter warfare, it's something that you can't see,

you can't touch it, but it's there. You feel it and it's powerful.

Q. What was causing these thoughts

to your --

A. Was causing?

Q. Yes.

A. Well, I believe deeply

everything was causing all that, it is Satanic practice against myself.

Q. And who initiated this Satanic

practice against you?

A. My father-in-law.

*****

All I was doing is seeking for

myself, destruction for myself. In doing so I kill someone else.

*****

Q. [N]ow, is this curse still

affecting you?

A. No.

Q. Why not?

A. It was very simple, because now

I found Jesus, I just have him in my heart and my life, so now I'm free

of all that. And in a way there is many things that I learned, and I

learned speaking to him here in jail. And one thing that he said, if you

keep my commandments you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make

you free. If you keep my commandments you'll be truly my disciple.

So that does not affect me any

more.

Q. Is there anything also about

what happened that night that you want this jury to know?

A. Well, one important thing is

that I never ever thought -- intend to kill her or to kill anyone. No, I

did it as the fact. I did it, but I -- no, that's the best way I can

explain to you. How it happened. I didn't want to do it, but it happened.

The Arlington County jury,

predictably, did not set him free. He was convicted on all charges.

After finding Angel guilty, the jury heard evidence pertinent to

sentencing.

The jury deliberated for

approximately 62 hours on the question of penalty. During its

deliberations, the jury twice sent out notes to the judge asking

questions that showed its struggle with the decision between life

imprisonment and death. The first question was, Awith life in prison how

long will he be there before he is eligible for parole? Ex. 16 at 115.

The trial judge instructed the jury

that he could not answer the question and the jury should not concern

itself with the possibility of parole. In colloquy with trial counsel,

the Court observed, Ait seems bizarre that we as a Commonwealth entrust

jurors with adecision like this and won=t tell them the reality of what

their choices are. Id.

The second question was whether the

jury can Arecommend the sentence of life without the possibility of

parole. Id. at 116. In response, the Court instructed the jury that it

must limit itself to the three choices previously outlined in the

instructions: death, life imprisonment, or life imprisonment plus a

fine. Ultimately, the jury fixed the sentence at death, and, on August

20, 1993, the trial judge held a sentencing hearing and imposed the

death sentence. Ex. 17.

In sum, throughout the trial

proceedings, due to his lack of understanding, Angel forced his American

court-appointed attorneys to take a number of steps, against their

advice, which were contrary to his best interest.

For example:

(a) Angel refused the proffered

plea agreement in which the Commonwealth would seek only a life sentence

if he would plead guilty, Ex. 14, & 5;

(b) Angel insisted upon testifying

on his own behalf, confessing his guilt, and explaining the events of

February 17, 1992 as the only eyewitness to them, id.;

(c) Angel urged his attorneys not

to call mitigation witnesses. They refused his directive on that

occasion, id., & 9;

(d) Angel refused to permit his

family members to be called as witnesses at the post-trial hearing on a

motion to set aside the death penalty, id.;

(e) Angel refused to permit his

attorneys to renew a pretrial motion to declare unconstitutional

Virginia=s method at that time of carrying out the death sentence, id.1

Never during the entirety of the

proceedings against him was Angel informed of his right to contact the

consulates of Paraguay and/or Argentina.

Nor were those consulates informed

of the detention and trial of their citizen or the imposition of the

death sentence upon him, despite the Commonwealths knowledge that Angel

was a foreigner. Ex. 13. Since becoming aware of his plight (from

sources other than American federal or state authorities), both Paraguay

and Argentina have made every effort to assist Angel and have made clear

that they would have done so sooner had they known of his arrest,

detention and trial.

Both nations have filed affidavits

in Angel's habeas corpus case describing the assistance they would have

provided to Angel. Exs. 19 & 20. Paraguay has also filed a separate

lawsuit in the courts of the United States and one in the International

Court of Justice in an effort to vindicate its own Vienna Convention

rights in connection with the proceedings against Angel. Argentina,

along with several other sovereign nations, submitted a brief amicus

curiae in support of Paraguay's Petition for Certiorari in the United

States Supreme Court. Virginia's Violation of the Vienna Convention

When a foreign national of a

signatory nation to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations is

arrested in another signatory nation, the Convention requires the latter

to notify the arrested person of his right to contact his consulate.

Article 36 of the Vienna Convention provides, in pertinent part:

1. With a view to facilitating the

exercise of consular functions relating to nationals of the sending

state:

(a) consular officers shall be free

to communicate with nationals of the sending state and to have access to

them. Nationals of the sending state shall have the same freedom with

respect to communications with and access to consular officers of the

sending state;

(b) if he so requests, the

competent authorities of the receiving state shall, without delay,

inform the consular post of the sending state if, within its consular

district, a national of that state is arrested or committed to prison or

to custody pending trial or is detained in any other manner. Any

communication addressed to the consular post by the

person arrested, in prison, custody or detention shall also be forwarded

by the said authorities without delay. The said authorities shall inform

the person concerned without delay of his rights under this sub-paragraph;

*****

2. The rights referred to in

paragraph 1 of this article shall be exercised in conformity with the

laws and regulations of the receiving state, subject to the proviso,

however, that the said laws and regulations must enable full effect to

be given to the purposes for which the rights accorded under this

article are intended. Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, Apr. 24,

1963, 21 U.S.T. 77, 590 U.N.T.S. 261 (emphasis added).

The Convention was ratified with

the advice and consent of the United States Senate in 1969, and is, thus,

one of the laws of the United States.To reinforce the Convention's

obligations, the United States State Department regularly sends notices

to governors, state attorneys general, and mayors of cities having a

population in excess of 100,000 advising them of their duties under the

Vienna Convention and the importance of complying with its terms. Ex.

21. Of particular import with respect to Angel's September 1992 arrest,

the State Department sent such notices to Virginia's Governor and

Attorney General in August 1991 and October 1992. Id., Exs. A & B.

The Vienna Convention is of great

significance, not only to foreign nationals detained in the United

States, but also to United States citizens traveling abroad who depend

on the observance of their rights under the Convention by other nations.3

Indeed, our State Department, speaking on behalf of American citizens,

has described one of the rights provided by Article 36 of the Vienna

Convention as follows: . . . the host government must notify the

arrestee without delay of the arrestee's right to communicate with the

American consul.

*****

[This] provides an opportunity for

the consular officer to explain the legal and judicial procedures of the

host government . . . at a time when such information is most useful.

United States Department of State,

7 Foreign Affairs Manual && 411.1, 412 ("Chapter 400") (emphasis added).

Ex. 23. According to the State Department, immediate access allows the

consular official to act as a cultural bridge between the arrested

person and the arresting state at the time of the arrestee's greatest

need to understand his rights under the foreign government's system of

laws, the legal and judicial procedures facing him, and the local

cultural norms. See id., && 401, 412. The State Department notes that no

one needs that cultural bridge more than the [individual] . . . who has

been arrested in a foreign country. . . . Id.

Moreover, as Judge Butzner wrote in

his concurring opinion in Angel's case in the Court of Appeals:

The protections afforded by the

Vienna Convention go far beyond Breard's case. United States citizens

are scattered around the world -- as missionaries, Peace Corps

volunteers, doctors, teachers and students, as travelers for business

and for pleasure. Their freedom and safety are seriously endangered if

state officials fail to honor the Vienna Convention and other nations

follow their example. Public officials should bear in

mind that "international law is founded upon mutuality and reciprocity .

. . ." Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 228 (1895).

*****

....The importance of the Vienna

Convention cannot be overstated. It should be honored by all nations

that have signed the treaty and all states of this nation. Breard v.

Pruett, 134 F.3d 615, 622 (4th Cir. 1998). Ex. 24.

The authorities of the Commonwealth

of Virginia have stipulated that Mr. Breard was not advised of his

rights to consular notification and access under Article 36 of the

Vienna Convention prior to being tried and sentenced to death in

Arlington County, Virginia in 1993. Ex. 13. The treaty explicitly

required that he be so advised. Notwithstanding the great weight

attached by the federal government to the Vienna Convention and to the

personal rights guaranteed by its provisions, the individual states have

long ignored legal obligations imposed upon them by the Convention.

Indeed, the District Court expressly found in Mr. Breard's case that

Virginia has engaged in a persistent refusal to abide by the Vienna

Convention. Breard v. Netherland, 949 F. Supp. 1255, 1263 (E.D. Va.

1996). Ex. 25.

It appears that violating the

requirements of Article 36 of the Vienna Convention is the norm, not

only in Virginia4, but throughout the United States.5 In fact, various

high state officials have publicly questioned the applicability and the

binding effect of the Convention with respect to the criminal law

enforcement activities of the states. Frank Green, a reporter for the

Richmond Times-Dispatch, wrote in an article in the September 17, 1997

edition concerning the murder conviction of Mexican Mario Murphy that

former Governor George F. Allen "disputed whether it was Virginia's

responsibility to notify Murphy of his Vienna Convention right." Ex. 27.

In that same case, the prosecutor

who oversaw the legal proceedings against Murphy was reported by The

Virginian-Pilot & Ledger Star of Norfolk to have described an assertion

of

rights under Article 36 as "completely ridiculous" and to question

whether such rights were enforceable: "I mean, what is the remedy? I

suppose Mexico could declare war on us." Ex. 28. The General Counsel to

Texas Governor George W. Bush reportedly protested a request by the U.S.

Department of State for information concerning possible violations of

Article 36 by Texas law enforcement officials on the ground that "the

State of Texas is not a signatory to the Vienna Convention." Al Kamen,

Virtually Blushing, The Wash. Post, June 23, 1997, at A17. Ex. 29. The

Executive Director of the Association of Retired Police Chiefs in

Washington, D.C. is reported to have stated about foreigners' Vienna

Convention rights that "[i]n my 47 years in law enforcement, I have

never seen anything from the State Department or FBI about this."

Margaret A. Jacobs, Some Convictions of Foreigners in U.S. Stir Debate

Over Rights, The Wall St. J., Nov. 4, 1997, at B5. Ex. 30.

It is apparent that Virginia

continues to violate the Vienna Convention despite the admonitions of

the court in two cases decided in 1996 by the United States District

Court and more recently affirmed by the Fourth Circuit where the

illegality of its Vienna Convention violations was a central issue. In

pre-trial proceedings held on March 3, 1998 in the first degree murder

case of Commonwealth of Virginia v. Elvia Garcia, Criminal No. 93264,

the Circuit Court of Fairfax County found that Virginia had violated Ms.

Garcia's Vienna Convention rights, but decided that it was unable to

provide her with any remedy for that violation. See Ex. 31 at 14-19.

Because the courts have found

themselves unable to remedy Virginia's defiant and continuing disregard

for the Vienna Convention, the Governor of Virginia must act to preserve

the fundamental protections provided by the Vienna Convention in this

country in order to prevent other signatories of the treaty from using

the conduct of Virginia and other states as a justification for similar

conduct. The United States interest in protecting these rights was

brought home by the lawlessness and barbarism of those who overran the

American Embassy in Tehran, Iran in 1979. Taking 52 American diplomats

and civilians hostage, Iran deprived them of all access to the outside

world for 444 days.

The United States reacted with

outrage and pressed its case before the International Court of Justice,

where it proclaimed to the world that Athe channel of communication

between consular officers and nationals must at all times remain open.

Indeed, such communication is so essential to the exercise of consular

functions that its preclusion would render meaningless the entire

establishment of consular relations. Memorial of the United States to

the International Court of Justice in the Case Concerning United States

Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran filed in response to the 1979

storming of the American Embassy.

In an earlier incident, the United

States protested Syria's 1975 arrest of two American citizens and its

failure to notify the American Embassy. Ronan Doherty, Foreign Affairs

v. Federalism, 82 Va. L. Rev., 1281, 1318 n.165 (1996), citing Luke T.

Lee, Consular Law and Practice 145 (2d ed. 1991). In a telegram to the

Syrian authorities, the United States felt it necessary to remind them

that the Vienna Convention was a solemn treaty obligation, and stated

that [t]he Government of the Syrian Arab Republic can be confident that

if its nationals were detained in the United States the appropriate

Syrian officials would be promptly notified and allowed prompt access to

those nationals. Id., quoting Department of State Telegram 40298 to

Embassy Damascus, Feb. 21, 1975. As matters have developed, however, any

such Syrian confidence would have been misplaced.

While state officials in Virginia

and elsewhere have thus far failed to recognize the rights granted by

the Vienna Convention, other nations have made extremely clear that they

take those rights very seriously. Paraguay and Argentina have submitted

in Angel Breard's habeas corpus case affidavits detailing the assistance

they would have provided to him; Paraguay and Mexico have brought

lawsuits in the courts of the United States to attempt to remedy

violations of their own Vienna Convention rights; Paraguay has taken its

complaint against Virginia and the United States to the International

Court of Justice; and Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Equador, and Canada

have filed briefs amicus curiae in cases in which violations of the

Vienna Convention have been alleged.

Paraguay's fledgling democracy is

dedicated to the implementation of democratic institutions and the rule

of law. Its perseverance in pursuing its Vienna Convention rights

signifies the depth of that commitment. A grant of clemency in this case

would thus support the cause of democracy abroad as well as the rule of

law at home in Virginia.

Angel Breard was offered a life

sentence in exchange for a guilty plea, and he rejected the bargain

because of his culturally based belief that the jurors would acquit him

once they understood that he had been under a satanic curse that had

been lifted when he found Christ. It is no answer that Angel had court-appointed

American trial counsel to advise him. He was deprived by the

Commonwealth of the cultural bridge he so desperately needed, a consular

official who had an understanding of both the North American and South

American cultures and legal systems.

While the courts have found

themselves unable to consider the merits of Angel's Vienna Convention

claim because of the doctrine of procedural default, the Governor is

under no such constraints. Now it is up to the Governor to assure that

Virginia abides by the rule of law, indeed, the Supreme law of the land.

The Virginia Supreme Court's

Defective Proportionality Review

Angel also requests clemency on the

grounds that his death sentence was the product of Virginia's

fundamentally flawed capital punishment system. Virginia, like many

states in the aftermath of Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976),

adopted statutory procedures for capital punishment like those upheld in

Gregg. One of the procedures mandated by state law is a proportionality

review of the sentence by the Virginia Supreme Court. Under Virginia's

procedure, the Supreme Court of Virginia is required to determine

Awhether the sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the

penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime and the

defendant. Va. Code Ann. ' 17-110.1(C)(2).

With respect to the required

proportionality review, the statute provides:The Supreme Court may

accumulate the records of all capital felony cases for such period of

time as the Court may determine. The Court shall consider such records

as are available as a guide in determining whether the sentence imposed

in the case under review is excessive. Va. Code Ann. ' 17-110.1(E) (emphasis

added).

While the Virginia Supreme Court is

required in every case to compare the death sentence under review with

the sentences imposed in similar cases throughout the state, that court,

in fact, compares any given case only to the cases previously reviewed

on appeal by that court. The effect of the Supreme Court's arbitrary

mechanism is dramatically illustrated by Angel's case. The majority of

capital cases similar to Angel's during the period 1985-1995 resulted in

a sentence less than death; however, only a small portion of those cases

were included in the Virginia Supreme Courts review because most had not

been appealed to that court. The same systemic error may infect the

proportionality review of every death case. The review of a skewed pool

of cases effectively denies capital defendants the statutorily mandated

review of "similar cases," depriving them of their life and liberty

interests without due process of law.

The Supreme Court of Virginia

devoted but one paragraph to its proportionality review of Angel's death

sentence. The Court initially correctly stated the test:

The test we must apply in

conducting the proportionality review is whether other sentencing bodies

in this jurisdiction generally impose the supreme penalty for comparable

or similar crimes, considering both the crime and the defendant. Breard

v. Commonwealth, 445 S.E.2d 670, 682 (Va.1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S.

971 (1994) (citing Jenkins v. Commonwealth, 244 Va. 445, 462, 423 S.E.2d

360, 371 (1992), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 1036 (1993)) (emphasis added).

In the next sentence, the Court wrote:

To guide us in applying the test,

we have compiled and examined the records of all capital murder cases

reviewed by this Court, including those in which a life sentence was

imposed. Id. at 682 (emphasis added). A denial of due process occurs

because the set of cases reviewed by this Court, that is those

previously appealed to that court, does not equal the set of Acapital

murder cases decided by other sentencing bodies. The Virginia Supreme

Court omits from its review those cases not appealed to the court. Death

cases are appealed directly to the Supreme Court, bypassing the

intermediate state Court of Appeals. Life sentence cases, if appealed at

all, go instead to the Court of Appeals with a follow up appeal to the

Supreme Court by petition. Va. Code Ann. '' 17-110.1(A);

17-116.05:1(A)(i); 17-116.08.

It is imperative that the Governor

review this issue carefully, for the courts, with one exception,

neglected it dismally, and the court that took note of the point

dismissed it based upon an erroneous application of the law. While Angel

raised the issue on direct appeal, see Ex. 32, the Virginia Supreme

Court ignored the point at that time and later, in state habeas

proceedings, mistakenly treated it as if it had been previously

defaulted. Breard v. Commonwealth, 248 Va. 68, 89, 445 S.E.2d 670,682

(1994); Breard v. Angelone, Order refusing Petition for Appeal (Jan. 17,

1996, Va. S.Ct.), Exs. 33, 35.

The United States District Court

remedied that particular error, ruling that the claim had not been

defaulted and quoting the language from Angel's brief on direct appeal

setting forth that claim:[A] defendant's liberty interest in

proportionality review is violated by the consideration of only those

cases which are reviewed by the Virginia Supreme Court.

Thus, the Court does not consider

those cases in which the death penalty was not imposed, which prevents

the Court from reviewing the types of cases in which death was not the

appropriate sentence. For these reasons the proportionality review

conducted by the Court constitutes a violation of the Defendant's due

process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. Breard v. Netherland, 949

F. Supp. at 1266.

The Court then, however, dismissed

the claim on other grounds. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals entirely

failed to address the issue, despite Angel's specific request in a

Petition for Rehearing that it do so. The United States Supreme Court

has not yet granted or denied Angel's Petition for Certiorari. The

Governor of Virginia is probably the only avenue to remedy this serious

deficiency in the Virginia Supreme Court's performance of the mandatory

proportionality review of death sentences. See Herrera v. Collins, 506

U.S. 390, 411-12 (1993) (clemency is the historic remedy for preventing

miscarriages of justice where judicial process has been exhausted); Ex

parte Grossman, 267 U.S. 87, 120-21 (1925) (executive clemency exists to

provide relief from harshness or mistake in the operation or enforcement

of the criminal law).

According to statistics in the

Presentence Investigation Database maintained by the Virginia Criminal

Sentencing Commission, an agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia (the

AVCSC Database), between January 1, 1985 and December 31, 1995, forty-three

persons were charged with capital murder under ' 18.2-31(5) of the Code

of Virginia (murder in the commission of, or subsequent to, rape, sodomy,

etc.) and convicted of some crime. Thirty-three of those individuals

were convicted of capital murder in violation of ' 18.2-31(5).

Of the thirty-three convicted of

capital murder, nineteen individuals (58%) were given a sentence other

than death and fourteen individuals (42%) were given the death penalty.

Of the life sentence cases, only two were ultimately appealed to the

Virginia Supreme Court. Thus, the Supreme Courts pool of similar cases

excludes the majority of all such convictions for the eleven year period

-- seventeen out of thirty-three (51%) -- and, more to the point,

excludes the vast majority of convictions in which a life sentence was

imposed -- seventeen out of nineteen (89%).

Angel had a due process right to a

proportionality review that conformed to the dictates of the Virginia

Code which requires the Supreme Court to determine whether the sentence

of death is Aexcessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in

similar cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.Va. Code Ann.

' 17-110.1(C)(2) (emphasis added). By limiting the pool to cases

previously appealed to the Supreme Court, that court so skewed the pool

that the required review was of no effect.

The effect of skewing the pool of

cases to be reviewed is apparent. The Virginia Supreme Court, in twenty

years of practice under the present death penalty statute, has never

reversed a death sentence because it was disproportionate. The Virginia

Supreme Courts procedures lead inexorably to this result.

An examination of the following

charts of cases in which a defendant was charged with capital murder

under ' 18.2-31(5) and convicted of a crime during the period 1985-1996

provides a glimpse at the universe of cases that should beconsidered by

the Virginia Supreme Court in its proportionality reviews. Such an

examination will also demonstrate that Angel's case does not fall within

a particular grouping of similar cases, in which the death penalty was

imposed, contrary to the dictates of the Code of Virginia for carrying

out the death penalty.

*****

Taking out the two cases decided in

1996, these cases represent approximately seventy percent of the forty-three

cases in the VSCS database referenced above. These cases demonstrate

that, in Virginia, the judge or jury does not generally impose the death

penalty for a certain type of crime or criminal defendant. Cf. Jenkins

v. Commonwealth, 244 Va. 445, 462, 423 S.E.2d 360, 371 (1992), cert.

denied, 507 U.S. 1036 (1993) ("On the question of disproportionality and

excessiveness, we determine whether other sentencing bodies in this

jurisdiction generally impose the supreme penalty for comparable or

similar crimes, considering both the crime and the defendant") (emphasis

added). Without minimizing the seriousness of Angel's crime, it is clear

that many cases involving facts more vile than those in this case and

defendants more dangerous than Angel have resulted in life sentences.

CONCLUSION

Angel has demonstrated his ability

to turn his life around and to become a spiritual leader and a

productive member of his religious and prison communities. He has

touched many lives in a positive way, and has brought spiritual healing

and consolation to people in prisons, hospitals, and the outside world

through his writings, his radio addresses, and his personal

relationships. He has demonstrated that he is a person who deserves to

live.

Moreover, the Commonwealth of

Virginia has engaged in a long-term pattern of misconduct that has

resulted in the denial of the Vienna Convention rights of foreigners, to

their severe detriment. As Judge Butzner observed, if other nations

follow the example of Virginia and other American states, the freedom

and safety of Americans traveling abroad will be seriously threatened.

In addition, Virginia failed to provide Angel with due process under its

own statutory procedures governing appellate judicial proceedings in

death penalty cases.

For these reasons, Angel Francisco

Breard respectfully requests that his death sentence be commuted to life

in prison.

Respectfully submitted,

ANGEL FRANCISCO BREARD

By Counsel